Amid the city districts of Cape Town, urban pocket forests are sprouting using the Miyawaki afforestation method, a Japanese technique that emphasizes growing dense, diverse forests of native and indigenous plant species. Mzanzi Organics and local elementary schools are utilizing this method to plant 800 indigenous trees and shrubs across 200 square meters of Langa, leading to the birth of the region’s first-ever forest. These green sanctuaries serve as alfresco classrooms for learning sessions and venues for music collaborations between musicians and pupils, while also encouraging biodiversity and ecosystem restoration.

Unfurling the Cape Town Green Revolution

How are urban pocket forests sprouting in Cape Town, and what is the Miyawaki afforestation method that is being used?

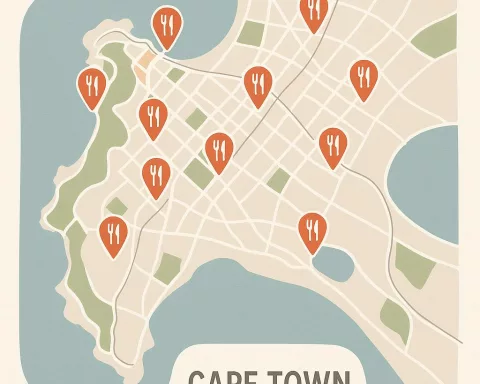

Amid the city districts of Langa, Mitchells Plain, Bo-Kaap, Pinelands, and Philippi, urban pocket forests are sprouting using the Miyawaki afforestation method. This Japanese technique, utilized by Mzanzi Organics and local elementary schools, emphasizes growing dense, diverse forests of native and indigenous plant species.

In the bustling city confines of Cape Town, a revolutionary eco-friendly crusade is blooming. Amid the city districts of Langa, Mitchells Plain, Bo-Kaap, Pinelands, and Philippi, urban pocket forests are sprouting. These green sanctuaries have been nurtured using the Miyawaki afforestation method, a Japanese technique utilized by Mzanzi Organics and local elementary schools to plant 800 indigenous trees and shrubs across 200 square meters of Langa, leading to the birth of the region’s first-ever forest.

The Emergence of Green Pockets

The sprouting of these green spaces commenced in January, and by March, the Langalibalele Forest stood as a living proof of the Miyawaki method’s effectiveness and the unwavering commitment of Mzanzi Organics and the local schools. Aghmad Gamieldien, the founder of Mzanzi Organics and a SUGi forest-maker, initiated this eco-friendly venture in densely populated, vulnerable urban areas after completing a 2021 fellowship on the Miyawaki forest approach with SUGi Pocket Forests. This not-for-profit entity is committed to encouraging biodiversity, ecosystem restoration, and rekindling the bond between communities and nature.

Collaboration for Biodiversity and Connection

On their mission, SUGi partners with forest growers like Gamieldien, nurturing pocket-sized forests across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and South America using the Miyawaki method. This technique emphasizes growing dense, diverse forests of native and indigenous plant species. In Cape Town’s green spaces, essential species such as the assegai, yellowwood, milkwood, red alder, and keurboom prosper without hindrance.

Intriguingly, the site where the Langalibalele Forest now thrives was formerly a waste dump. “During the clean-up with machines, we came across heaps of refuse accumulated over the years due to illegal dumping,” revealed Gamieldien. The forest draws its name from Hlubi king Langalibalele, who was incarcerated on Robben Island for leading a rebellion against the British and Dutch colonial rulers of the Natal Government in the late 1870s. His name, which translates to ‘The Sun that Shines,’ combined with his eventual relocation to the area now known as Langa post his release from Robben Island, adds a significant historical touch to the forest.

The Urban Gem: Langalibalele Forest

What makes the Langalibalele Forest an urban marvel in Cape Town is not just its ecological significance – it has also blossomed into a hub for community activities. It serves as an alfresco classroom for learning sessions and a venue for music collaborations between musicians and pupils.

The inaugural urban pocket forest in Cape Town, nestled on the KT Grows organic farm in Philippi, functioned as a trial project and is now over two years old. Riding on its success, the second forest, the Khoi First Nations Forest, sprouted at the Oude Molen Eco Village in Pinelands. This larger forest, spreading over 200 square meters and containing 600 trees, is steadily progressing toward self-sufficiency. “After two years, the forest becomes self-sustaining…It’s genuinely extraordinary,” remarked Gamieldien.

Furthermore, the Cape Flats forest was planted in association with the Seed Abundance community at Rocklands Primary in Mitchells Plain. Spanning 300 square meters, it overflows with 1,200 indigenous trees and shrubs and includes an open-air classroom for educational activities.

Challenges and Commitment to Green Transformation

The Schotche Kloof Forest, although smaller with just 100 trees within 25 square meters, is located at the Schotche Kloof Primary School in Bo-Kaap. The school community warmly welcomed it, taking immense pride in its upkeep and maintenance. “The school embraced the forest wholeheartedly, actively participating in every stage, from digging and planting to ongoing care,” added Gamieldien.

One of the project’s hurdles has been securing government land in Cape Town. Consequently, the project has concentrated on collaborating with schools, which are more accessible. Nevertheless, despite some mishaps, such as thefts of water drums in Mitchells Plain, Gamieldien’s commitment to the broader vision of green transformation in urban landscapes remains unflinching. This path of urban reforestation displays the potential of sustainable practices in reshaping not only our landscapes but also our societies and our relationship with nature. These urban pocket forests in Cape Town indeed shine as a beacon of hope for a greener, more sustainable future.

1. What is the Miyawaki afforestation method?

The Miyawaki afforestation method is a Japanese technique that emphasizes growing dense, diverse forests of native and indigenous plant species.

2. Where are urban pocket forests sprouting in Cape Town?

Urban pocket forests are sprouting in the city districts of Langa, Mitchells Plain, Bo-Kaap, Pinelands, and Philippi.

3. What is the Langalibalele Forest?

The Langalibalele Forest is the first-ever forest in the Langa region, created using the Miyawaki afforestation method and planted with 800 indigenous trees and shrubs across 200 square meters by Mzanzi Organics and local elementary schools.

4. What is the significance of the Langalibalele Forest in Cape Town?

Apart from its ecological significance, the Langalibalele Forest serves as an alfresco classroom for learning sessions and a venue for music collaborations between musicians and pupils, making it a community hub for activities.

5. What are some of the challenges faced by the project?

One of the challenges faced by the project is securing government land in Cape Town. As a result, the project has concentrated on collaborating with schools, which are more accessible.

6. What does the future look like for urban pocket forests in Cape Town?

The success of the Langalibalele Forest and other urban pocket forests in Cape Town displays the potential of sustainable practices in reshaping not only our landscapes but also our societies and our relationship with nature, showing a path of urban reforestation for a greener, more sustainable future.