In Gauteng, the EFF challenges Kleinfontein, a settlement where only Boere-Afrikaners live, calling it unfair and against South Africa’s promise of equality. They say places like Kleinfontein keep old racial divides alive, blocking true freedom and unity. The EFF’s fight is more than protest—it’s a push to remake cities so everyone shares space and opportunity. Meanwhile, Kleinfontein’s people say they just want to protect their culture. This clash shows how South Africa struggles to balance respecting different cultures while breaking down barriers from its past.

What is the conflict between the EFF and Kleinfontein in Gauteng?

The EFF opposes Kleinfontein, an exclusive Boere-Afrikaner settlement, due to its racial and spatial segregation. They argue it violates South Africa’s constitutional principles of equality and inclusivity, demanding enforcement of laws to dismantle apartheid-era geographic divisions and promote spatial justice.

The EFF’s Campaign for Justice

As dawn breaks across Gauteng, a palpable sense of determination sweeps through the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). This political movement, renowned for its unwavering advocacy of equality and anti-racism, readies itself to confront Kleinfontein, a controversial enclave lying east of Pretoria. Kleinfontein, more than just a physical settlement, has become emblematic of South Africa’s ongoing struggle with its tumultuous past and the promises of its democratic future.

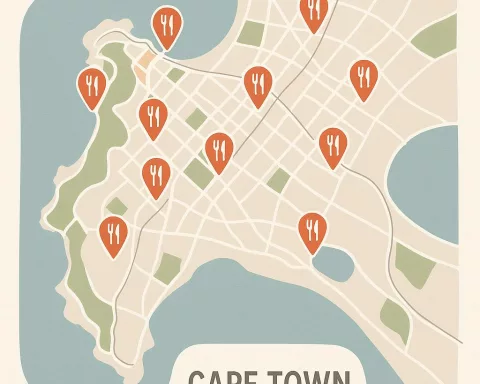

The origins of Kleinfontein trace back to 1992, a transformative period on the brink of South Africa’s first democratic elections. At that time, many Afrikaners, anxious about the looming end of apartheid, sought to carve out insulated spaces where their traditions and language could flourish away from the uncertainties of the new order. Kleinfontein emerged from this desire for security—a sprawling 900-hectare settlement that only admits individuals who identify as “Boere-Afrikaners.” Today, around 1,500 residents call it home, maintaining strict cultural and membership criteria.

Approaching Kleinfontein, visitors cannot help but notice the deliberate evocation of a bygone era. Afrikaans language, historical monuments, and rituals reinforce a narrative of exclusivity that lingers from the days of institutionalized segregation. Surveys such as those conducted by Afrobarometer consistently reveal how, even decades after the end of apartheid, cultural enclaves with defensive postures persist across South Africa. In Kleinfontein, this nostalgia becomes a mechanism for survival, but also a flashpoint for national controversy.

Legal Battles and Revolutionary Response

The EFF’s march on Kleinfontein is far from a spontaneous gesture. Julius Malema, the party’s spirited figurehead, frames this move as part of a broader, unfinished liberation. EFF members, always visible in their signature red berets, channel the language and spirit of past anti-apartheid struggles, insisting that true freedom remains incomplete while racial enclaves like Kleinfontein endure. For them, this settlement is not merely an outlier; it stands as a living repudiation of post-1994 ideals—namely, equality, dignity, and inclusivity. The EFF’s rhetoric casts Kleinfontein as a direct violation of the social contract that modern South Africa seeks to uphold.

Recent events have further intensified this confrontation. Only weeks before the EFF’s planned march, the Gauteng High Court in Pretoria handed down a ruling that reverberated far beyond the legal community. The court found Kleinfontein to be in breach of zoning and municipal planning regulations, and ordered the City of Tshwane to enforce compliance. This ruling has widely been interpreted as a stand against spatial exclusion, echoing the ideals enshrined in South Africa’s constitution and decisively rejecting any attempts to perpetuate apartheid-era geography.

Capitalizing on this legal victory, the EFF issued renewed calls for municipalities to reject any applications that would re-entrench racial or economic exclusion. Their vision extends beyond simple protest—they demand a South Africa where land use and city planning actively dismantle the legacy of apartheid. The party’s invocation of concepts like “spatial justice” aligns with the work of urban theorists such as Edgar Pieterse and AbdouMaliq Simone, who argue that the very layout and organization of cities serve as battlegrounds for democracy and equality.

Cultural Identity and Constitutional Dilemmas

Kleinfontein’s supporters, however, present a starkly different interpretation of their community’s purpose. They argue that their enclave serves as a sanctuary for cultural preservation, not a tool for division. Invoking constitutional protections for cultural communities, these residents contend that Kleinfontein enables them to practice their traditions and maintain their identity amid rapid societal change. For many, the fear of cultural erasure feels as pressing as the imperative of national inclusion.

This conflict highlights a deep constitutional dilemma: How does South Africa balance individual and community rights with the collective pursuit of justice and equality? On one hand, the constitution defends cultural expression and association; on the other, it commits the nation to overcoming the spatial and social divides that apartheid left behind. Kleinfontein thus becomes a crucible for debates about belonging, exclusion, and the meaning of freedom in a diverse society.

The EFF remains adamant in its opposition. Their leaders assert that any form of racial exclusivity, whether overt or subtle, cannot be tolerated. In their view, the march against Kleinfontein is more than a political statement—it is a rallying call for all citizens who believe in the transformative potential of democracy. By inviting civil society, progressive groups, and the general public to join them, the EFF aims to build a broad-based movement against all manifestations of exclusion in South Africa.

The Wider Struggle for Space and Equality

The controversy surrounding Kleinfontein stands at the intersection of broader national debates on economic and spatial justice. South Africa’s cities and towns remain deeply marked by the divisions of the past, with gated communities, under-serviced townships, and exclusive resorts echoing patterns established decades ago. Artists like David Goldblatt have documented these landscapes of segregation, while novelists such as Nadine Gordimer and Zakes Mda have explored their psychological and emotional impacts.

The EFF frames their opposition to Kleinfontein within their broader anti-capitalist platform, arguing that economic marginalization is inseparable from racial exclusion. They contend that communities designed to exclude not only perpetuate the inequalities of the past but also reinforce contemporary barriers to opportunity. For the EFF, the transformation of spatial planning is essential to meaningful redistribution and the healing of historical wounds.

Even as Johannesburg’s Maboneng district showcases urban revitalization and the promise of a new future, countless neighborhoods remain shaped by the inequalities of the past. The EFF’s mobilization against Kleinfontein is, in essence, a call to reimagine the very fabric of the South African city. They urge planners, lawmakers, and citizens alike to see spatial justice as a prerequisite for reconciliation and genuine development.

Globally, the issues raised by Kleinfontein resonate in other societies grappling with the persistence of segregation. Debates over “sundown towns” in the United States, or the rise of ethnic enclaves in Europe, show that the challenge of balancing cultural preservation with social inclusion is by no means unique to South Africa. These international parallels underscore just how complex and urgent the quest for inclusive citizenship remains.

Towards a Shared Future

The planned EFF march on Kleinfontein captures the hopes and anxieties of a nation still wrestling with its identity and direction. The act of confronting such enclaves is not simply about one community or another—it is a symbolic struggle over the meaning of democracy, the promise of the constitution, and the realities of lived experience. As South Africans look to the future, questions of space, belonging, and justice will continue to shape the nation’s path.

Ultimately, the heart of the Kleinfontein dispute lies in a question that has yet to find a definitive answer: what does it truly mean to belong in a post-apartheid society? The answer, contested and evolving, will unfold not only in the courts and the streets, but in the collective imagination of all who call South Africa home. The battle for spatial and social justice remains unfinished—but through persistent activism, legal change, and public dialogue, new possibilities for unity and equality continue to emerge.

What is the conflict between the EFF and Kleinfontein in Gauteng?

The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) oppose Kleinfontein because it is an exclusive Boere-Afrikaner settlement that only admits residents who identify as Boere-Afrikaners. The EFF argues that this exclusivity perpetuates racial and spatial segregation, which violates South Africa’s constitutional principles of equality, dignity, and inclusivity. They view Kleinfontein as a symbol of ongoing apartheid-era divisions that block true freedom and unity. The EFF demands enforcement of laws to dismantle such racial enclaves and promote spatial justice.

Why does Kleinfontein exist as a Boere-Afrikaner only settlement?

Kleinfontein was founded in 1992, during South Africa’s transition to democracy, by Afrikaners seeking to preserve their culture, language, and traditions amid uncertain political changes. It spans about 900 hectares east of Pretoria and admits only those who identify as Boere-Afrikaners. Residents argue that Kleinfontein is a cultural sanctuary aimed at protecting their heritage, not a tool for racial division. They invoke constitutional protections for cultural communities to justify their exclusivity.

What legal actions have influenced the conflict over Kleinfontein?

Recently, the Gauteng High Court ruled that Kleinfontein is in breach of zoning and municipal planning laws. The court ordered the City of Tshwane to enforce compliance, signaling a rejection of spatial exclusion and apartheid-era geographic segregation. This legal decision has strengthened the EFF’s position, empowering them to call on municipalities to deny any applications that would reinforce racial or economic exclusion, aligning with South Africa’s constitutional commitment to equality.

How does the EFF frame its opposition to Kleinfontein?

The EFF sees its campaign against Kleinfontein as part of a broader struggle for liberation and social justice that remains unfinished since apartheid’s end. They argue that any racial exclusivity, whether explicit or subtle, undermines democracy and the social contract of the post-1994 South Africa. The EFF links spatial segregation to economic marginalization and insists that transforming city planning and land use is crucial for meaningful redistribution, equality, and reconciliation in the country.

What constitutional dilemmas does the Kleinfontein dispute highlight?

The conflict illustrates the tension between protecting cultural identity and pursuing social justice. South Africa’s constitution safeguards cultural expression and community rights but also mandates overcoming apartheid’s spatial and social divisions. Kleinfontein raises difficult questions about how to balance the right of groups to preserve their culture with the need to promote inclusiveness, equality, and unity in a diverse society. This dilemma remains unresolved and is central to ongoing debates about belonging and freedom.

How does the Kleinfontein controversy relate to wider global issues?

The issues around Kleinfontein resonate internationally with debates over racial and ethnic enclaves in other countries, such as “sundown towns” in the United States or ethnic neighborhoods in Europe. These examples show that balancing cultural preservation with social inclusion is a common and complex challenge worldwide. The South African case underscores the importance of addressing spatial justice as a key part of democratic development and social cohesion, with lessons applicable to many societies confronting legacies of division.