South African women, especially grandmothers and early childhood workers, quietly shape the future by caring for and teaching young children in homes and community centers. Their loving work, often unpaid or underpaid, builds the skills and confidence children need to succeed in school and life. Despite facing many challenges, these women show incredible creativity and strength, turning simple spaces into places full of learning and joy. With growing government support and community efforts, their vital role is finally gaining the recognition it deserves. Their hands nurture not just children, but the very heart of the nation’s tomorrow.

How are South African women shaping early childhood development (ECD)?

South African women, especially grandmothers and ECD workers, play a crucial role in early childhood development by providing nurturing care, education, and support. They work in homes and learning centers, often unpaid or underpaid, laying the foundation for children’s growth, school readiness, and the nation’s future.

Unsung Architects of a Nation’s Future

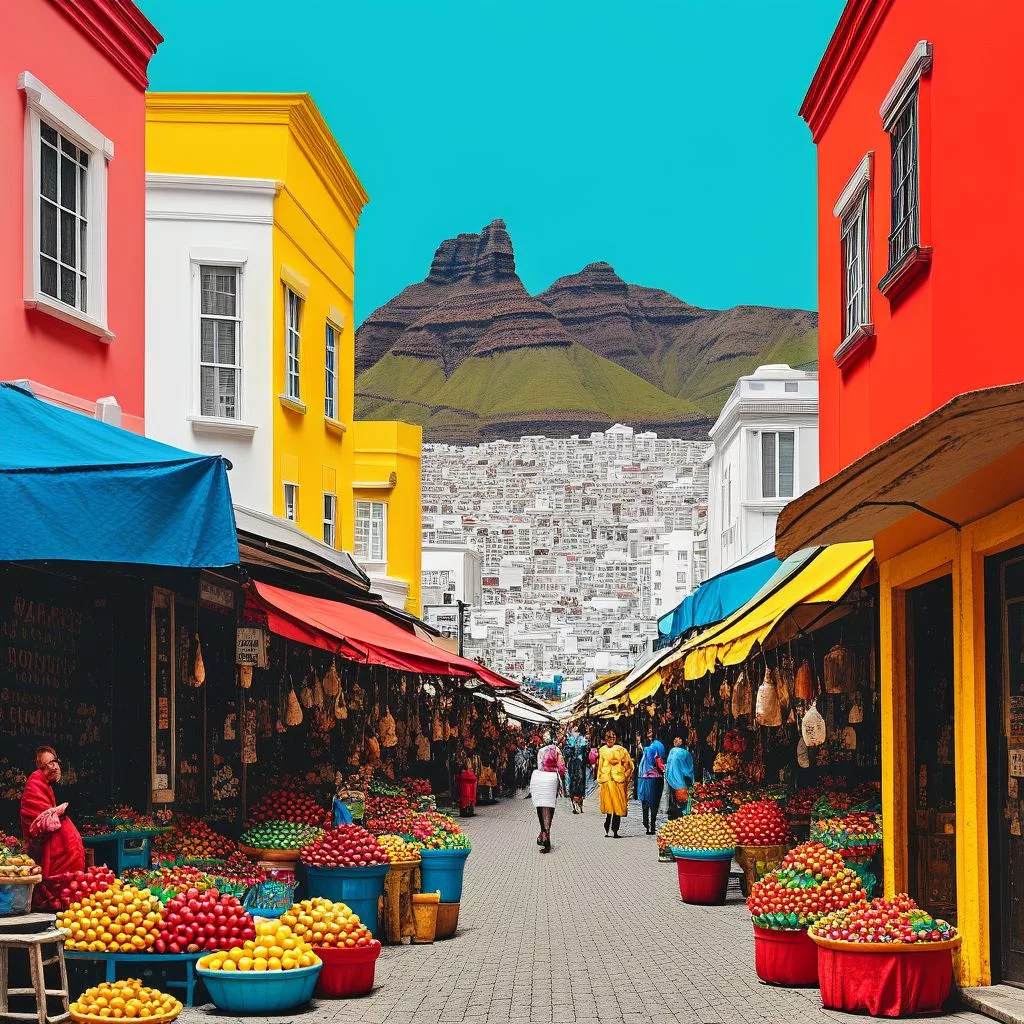

Before daylight bathes townships and rural villages across South Africa, a quiet movement has already begun. Women – often invisible to mainstream narratives – lead this change as they shape the foundation of early childhood development (ECD). In kitchens, classrooms, and backyard spaces, their daily rituals lay the groundwork for the nation’s next generation. Though their efforts rarely attract fanfare, their influence is profound and enduring.

Across communities neglected by urban opulence, these women sweep floors, set up makeshift learning spaces, and prepare simple meals. The aroma of freshly made porridge mingles with the sounds of young laughter, signaling the start of another day filled with learning and opportunity. Every toy they set out and each lesson they share plants seeds of curiosity and potential, echoing the values of the historic Arts and Crafts Movement, where hands-on skill and heartfelt care defined quality.

Many of these caregivers are grandmothers – affectionately called gogos – who bear the future in their arms. They wake early to feed, dress, and nurture their grandchildren, allowing the children’s parents to head off to work, often miles away. In those early morning hours, the home transforms into a place of both refuge and learning. Simple tasks such as sharing breakfast become powerful moments of connection, community, and growth.

The Backbone of Early Learning

Beyond family kitchens, thousands of women work or volunteer at informal and formal early learning centers. Here, they provide not only supervision but the structure that young children need to thrive. These women act as teachers, guides, and custodians – helping children develop the skills they’ll need to build their futures and, by extension, the nation’s.

Recent data underscores the vast scale of their work. The 2022 national ECD Census documented more than 420,000 early learning programs, enrolling roughly 1.66 million children and employing close to 200,000 workers. Estimates now suggest that as many as 250,000 people work in ECD, with women forming the overwhelming majority. Despite their essential roles, most ECD workers earn less than the national minimum wage – a stark reminder of the undervaluation of caregiving in South Africa.

Behind these statistics lies a larger, invisible workforce: unpaid caregivers. Research from Statistics South Africa reveals that 6.7 million grandparents reside with nearly 9.7 million children. Grandmothers make up about 70% of these caregivers, shouldering enormous responsibilities every day. Through their daily sacrifices, millions of parents can participate in the economy, and the country’s progress rests on their unheralded labor.

Comparing these women to nurturing figures immortalized in Renaissance art feels apt. Like their artistic counterparts – silent supporters of great works – modern South African women seldom receive acknowledgment. Women’s Month briefly spotlights their achievements, but genuine recognition requires more than ceremonial gestures; it demands meaningful change in policy and perception.

Challenges and Progress in Early Childhood Development

Looking closely at developmental outcomes, the urgency for greater support becomes clear. The latest 2024 Thrive by Five Index shows that less than half of four- and five-year-olds in early learning settings reach the expected milestones for school readiness. Only 43% meet benchmarks in both physical growth and foundational abilities such as language, problem-solving, and motor skills. Focusing solely on early learning skills lifts the figure only to 45.7%. This means the majority of children enter school already behind, which is troubling for anyone who cares about the nation’s future.

Creating nurturing and stimulating early environments is essential, not optional. Educational reformers from Pestalozzi to Montessori have long argued that the earliest years are critical for lifelong growth. Consistent, loving attention at this stage shapes children’s ability to learn, connect, and thrive.

Yet, recent policy shifts offer a measure of hope. The Minister of Finance announced an additional R10 billion for ECD over the medium term, and the government increased the subsidy for center-based programs from R17 to R24 per child per day – the first hike in six years. This expansion will bring support to 700,000 more children. While this represents progress, the new subsidy still falls short of what’s needed for quality programs, and only about one in three eligible children receives this assistance.

Sustaining and expanding this support presents ongoing challenges. The R24 subsidy must be regularly evaluated to keep up with changing needs, and efficient systems are necessary to ensure timely delivery of funds. Bureaucratic delays often hold up resources, undermining the work of ECD centers. Government strategies like the Department of Basic Education’s 2030 ECD Strategy aim to integrate more community and home-based programs into the formal system, but registration backlogs hinder many from accessing subsidies. New digital platforms such as eCares and the Bana Pele registration drive seek to simplify this process, encouraging micro-entrepreneurs and ECD practitioners to formalize their services and secure deserved support.

Internationally, similar calls for reform resonate. At the G20 Education Indaba, leaders emphasized the need to prioritize foundational learning and streamline ECD center registration, moving past isolated pilot projects. These policy shifts are not abstract – they are necessary steps to ensure resources reach the grassroots educators and caregivers who make the biggest difference.

Celebrating Innovation, Resilience, and Community

Recognition must extend beyond policy to honor the full spectrum of women’s contributions as caregivers, teachers, and community leaders. While society often applauds women in traditionally prestigious professions, the foundational work of childminders, homemakers, and early learning facilitators receives little attention. Yet, their everyday acts – teaching first words, responding to first tears – provide the bedrock upon which all future achievements stand.

History is rich with artistic and literary tributes to caregivers. Virginia Woolf described the “angel in the house” – the quiet, self-sacrificing woman whose invisible labor sustains families. Today, South Africa’s ECD practitioners reject invisibility, embracing creativity and entrepreneurship. They open micro-businesses, develop innovative teaching methods, and transform humble spaces into vibrant centers for growth. Their resourcefulness, reminiscent of women during the Great Depression, enables families and communities to weather economic hardship with dignity and grace.

Recent years have seen a flourishing of community-driven ECD initiatives. From toy libraries to mobile classrooms, these programs operate with minimal resources but extraordinary commitment. Storytelling festivals, puppet performances, and interactive music sessions bring joy and inspiration to children’s learning journeys. These creative, nurturing spaces promote holistic development and ensure that artistry and play remain central to early education.

Non-profit organizations and social enterprises have stepped forward to offer training and support for ECD professionals. Programs now emphasize not just academic skills but emotional intelligence and overall well-being. Drawing on global best practices and tailoring them to local realities, these organizations work to ensure that every child – regardless of origin – receives the support, stimulation, and care required to flourish.

This interconnected web of care, ingenuity, and determination drives South Africa forward. While engineers and architects construct the country’s physical infrastructure, women caregivers build its true foundation – its people. Their legacy is written not in stone or steel, but in the laughter and dreams of the children whose lives they touch.

The Road Ahead: Recognizing and Supporting the Pillars of ECD

South Africa’s future depends on the invisible yet essential work of its women caregivers. Their dedication and resilience sustain families, communities, and the nation at large. As new policies and funding bring the promise of change, continued advocacy is needed to ensure that ECD professionals receive fair compensation, sufficient resources, and the societal respect they deserve.

By investing in early childhood development, the country not only empowers its youngest citizens but also honors those who light the way – often in silence, always with love. True progress will come when every woman who works for the future receives the recognition, support, and celebration she has long earned.

FAQ: South Africa’s Women Shaping Early Childhood Development

1. How do South African women contribute to early childhood development (ECD)?

South African women, particularly grandmothers (gogos) and early childhood development workers, play a vital role in nurturing and educating young children both at home and in community or formal learning centers. They provide care, teach foundational skills, and create safe, stimulating environments that prepare children for school and life. Much of this work is unpaid or underpaid, yet it forms the backbone of the nation’s future.

2. Who are the main caregivers involved in ECD in South Africa?

The primary caregivers include grandmothers, mothers, and women working as early childhood practitioners in both informal and formal settings. Grandmothers are especially significant, with research showing they make up about 70% of the 6.7 million grandparents living with nearly 9.7 million children in South Africa. Beyond family, thousands of women run or volunteer in over 420,000 early learning programs, making women the overwhelming majority of the approximately 250,000 ECD workers nationwide.

3. What challenges do women in ECD face in South Africa?

Despite their essential role, most ECD workers earn less than the national minimum wage, reflecting a broader undervaluation of caregiving. Many operate in informal settings with limited resources, face bureaucratic hurdles for subsidies and registration, and struggle to secure consistent funding. Additionally, developmental outcomes show that less than half of children in early learning meet school readiness benchmarks, underscoring the need for better support and quality programs.

4. What progress has been made to support ECD in South Africa?

Recent government efforts include an increased subsidy for center-based ECD programs – from R17 to R24 per child per day – and an additional R10 billion allocated over the medium term. These measures aim to extend support to 700,000 more children. The Department of Basic Education’s 2030 ECD Strategy and digital platforms like eCares and Bana Pele are designed to streamline registration and funding access, encouraging formalization of micro-entrepreneurs and practitioners.

5. How do community initiatives and innovations enhance ECD?

Community-driven programs creatively transform limited spaces into vibrant learning environments through toy libraries, mobile classrooms, storytelling festivals, puppet shows, and interactive music sessions. Nonprofits and social enterprises provide training that integrates academic skills with emotional intelligence and well-being, ensuring holistic child development. These grassroots efforts showcase the resilience and entrepreneurship of women caregivers, fostering joyful and effective early learning despite economic challenges.

6. Why is recognizing and supporting women caregivers important for South Africa’s future?

Women caregivers are the foundation of South Africa’s human capital and social fabric. Their daily efforts nurture the next generation and enable parents to participate in the workforce. Proper recognition, fair compensation, and adequate resources are crucial not only for their dignity and livelihood but also to improve developmental outcomes for children. Investing in these women means investing in the nation’s long-term growth, resilience, and prosperity.