{“summary”: “Childhood in the Cape Flats during apartheid was a time of incredible resourcefulness and resilience. Kids turned old cars into submarines and empty lots into the Serengeti, using their imaginations to escape the harsh reality. Even though classrooms were crowded and danger was always near, they found strength in each other, sharing answers and comfort. Despite the tough times and lack of resources, their spirits were undefeated, always finding ways to play, learn, and hope. It was a childhood shaped by hardship but also by an amazing ability to adapt and thrive.”}

What was childhood like in the Cape Flats during apartheid?

Childhood in the Cape Flats during apartheid was characterized by resourcefulness and resilience amidst hardship. Children transformed their environment into imaginative play spaces, learned in overcrowded classrooms, and developed a strong sense of community support. They adapted to violence and scarcity, finding ways to cope and thrive despite systemic challenges.

1. Concrete Savannah

Mitchells Plain was never meant to be a playground.

The avenues were drawn with rulers on apartheid desks, their only purpose to keep the “non-white” ocean from washing against the white city’s sea-wall.

We flipped that grid into a private atlas: the gutted Morris Minor became a yellow submarine, the storm-water tunnel morphed into the Nile, and “Die Veld” – a rectangle of knee-high grass – was our Serengeti where mop-stick spears hunted imaginary lions.

School happened in overcrowded classrooms that smelled of chalk dust and methylated spirits.

Forty-five bodies shared three sticks of coloured chalk; the teacher’s cane wrote its own curriculum in the air.

If letters jig-sawed on the page or your tongue tripped over “February”, you were simply “slow” – no one asked whether the page or the world was spinning faster than your mind.

Beneath the strict silence, an invisible bazaar of mercy thrived.

The girl who finished her maths first let the boy with cramped fingers copy her answers; the fluent reader whispered paragraphs to the kid whose mouth felt full of wet cement.

We were speech therapists, occupational coaches and trauma counsellors rolled into one, trading help with nudges, smile-codes and the solemn vow never to laugh at a stutter.

2. Curriculum After the Bell

When the final bell clanged, the actual syllabus unfurled on the street.

Twenty-five cents bought a paper cone of neon-pink chillies; another ten secured standing room in a petrol-scented garage where “Dik-Dik” screened Rocky II on a wobbling TV.

When Eskom pulled the plug, we improvised the rest of the movie with our mouths, until Balboa became a Klippies-and-milk champion who could knock out Russians with a bottle.

Technology crept in like contraband.

My uncle, a radio repairman from Athlone, arrived with a Commodore 64 whose cassette deck gasped like an old man climbing stairs.

Pitfall Harry’s pixel vines felt like rehearsal for real escapes; none of us guessed that those 64 kilobytes would one day inflate into clouds that tag township children before they can spell their surnames.

Medical labels reached us last, translated and bruised.

ADHD landed as “hyperaktiewe sindroom”, dyslexia shrank to “leesprobleme”, autism was dismissed as “vertraagd” – luxury goods advertised after the nine-o’clock news for Rondebosch kids.

The chemist stocked Grand-Pa and cough syrup, not Ritalin, so the restless kept sprinting until their soles flapped like tired orange peel.

3. Gunpowder in the Air

In 1985 the Cape Flats became a war zone overnight.

Buffels and Casspirs roared down our avenues, rifles pointing at shadows; BBC reporters quoted our survival odds between cricket scores.

My mother choreographed a kitchen-floor drill – flatten, crawl, breathe – timed to the percussion of rubber bullets slapping vibracrete.

Even under military curfew, childhood mutated rather than died.

We replaced “cops and robbers” with “casspir-casspir”, using wheelie bins as armour and chanting struggle songs we barely understood.

Death strolled in casually: one December a neighbour’s big brother was shot during a march; we carried on with tape-ball cricket while the hearse idled outside Number 42, because the scoreboard had to keep ticking or the sky would fall.

Grief had no glossary.

We traded sadness through eye contact, then erased it with a joke before supper; the closest thing to therapy was the dominee’s grave-side prayer and a plate of triangular sandwiches.

Resilience was not a buzzword but a second skin: you spun a rugby ball until it hovered like a comet, bunny-hopped a borrowed BMX, or memorised every Madonna lyric so that escape sounded like a synth riff.

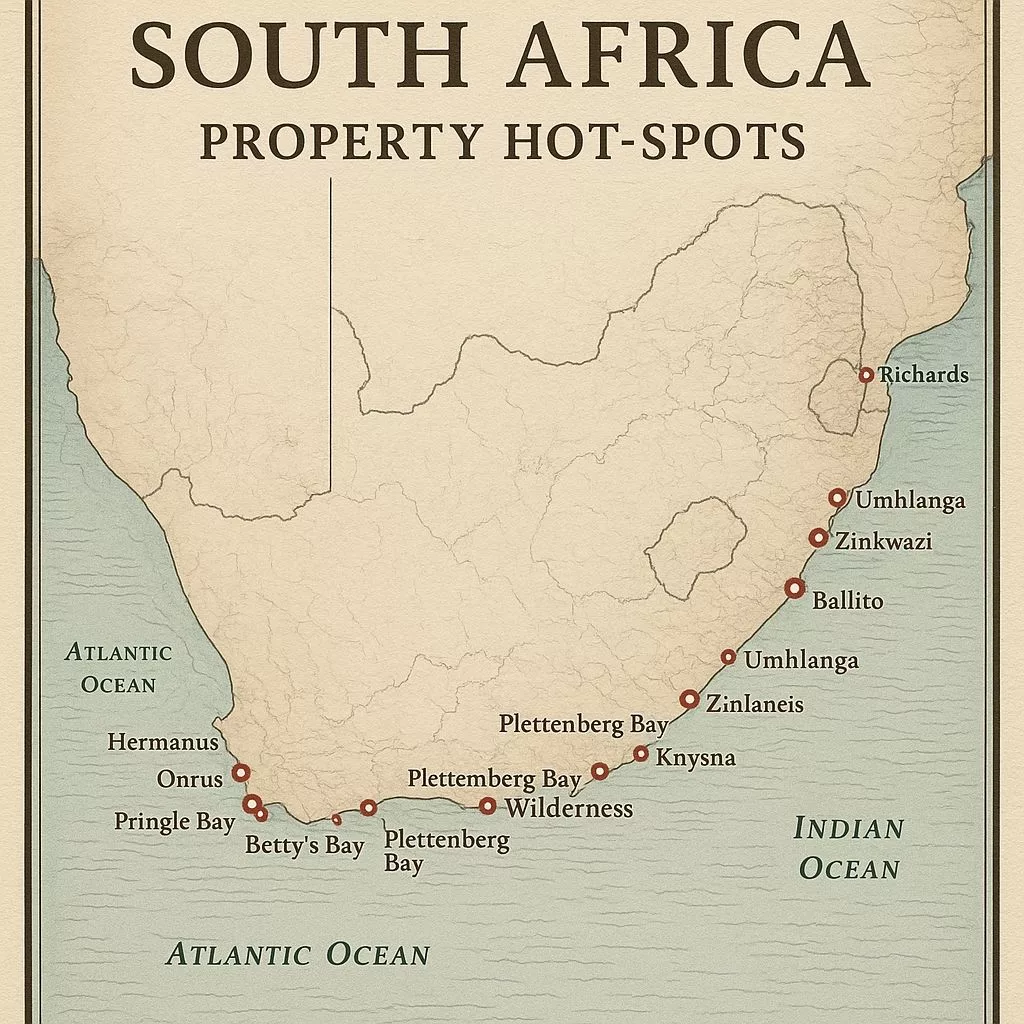

4. Fibre, Fear and the Future

Thirty years later the same poles that once carried surveillance microphones now hoist fibre-optic cables.

Kids queue for methylphenidate while their parents swipe through “ADHD Moms CT” Facebook feeds; smartboards and educational psychologists tote slogans about neurodiversity.

Yet WhatsApp still pings with updated hit lists, and mortuary vans collect bodies before the morning register is called.

Diagnoses have grown precise but porous.

A child branded “oppositionally defiant” will still duck when a scooter backfires; another labelled “twice-exceptional” might ace robotics but still tiptoe past the spot where a classmate caught a stray bullet.

Labels map inner galaxies while outer minefields stay active.

Abundance has bent time until it scrolls.

Where we once waited months to photocopy a Liverpool crest, today’s ten-year-old streams 4K goals before the final whistle.

Scarcity taught us to stretch minutes; algorithmic feeds compress them into dopamine hits calibrated to the millisecond.

Hope sprouts in unlikely cracks.

Libraries stock isiXhosa picture books that portray therapy as normal; barbers hand out free fades to boys who can recite the suicide hotline.

At a Lentegeur primary, Grade 6 learners practise box-breathing before maths, their bellies rising like shy moons over the examination horizon.

Even grandmothers have gone high-tech, hosting a Saturday radio slot called “Ouma’s Couch” where they debunk psychiatric myths in Kaaps and prescribe turmeric tea for the grandchildren’s panic.

Their diagnosis is still delivered in metaphor – “Daai kind draai draai, hy soek ‘n plek om stil te word” – but now it streams on podcast apps and earns citations in Columbia University dissertations.

Morning breaks over the same kerb where soldiers once shouldered rifles.

A boy lands his first skateboard ollie; a girl with vitiligo live-streams a homemade spectroscope that splits sunlight into its true colours.

Heart emojis rain down like distant gunfire, and for a moment the concrete savannah becomes a launchpad, proof that even white light carries multitudes, and that childhood – relabelled, rewired, but undefeated – will keep inventing itself faster than any system can name it.

[{“question”: “What was childhood like in the Cape Flats during apartheid?”, “answer”: “Childhood in the Cape Flats during apartheid was characterized by resourcefulness and resilience amidst hardship. Children transformed their environment into imaginative play spaces, learned in overcrowded classrooms, and developed a strong sense of community support. They adapted to violence and scarcity, finding ways to cope and thrive despite systemic challenges.”}, {“question”: “How did children in the Cape Flats use their imagination to cope with their surroundings?”, “answer”: “Children in the Cape Flats were incredibly resourceful, turning everyday objects and spaces into imaginative playgrounds. For example, a gutted Morris Minor became a ‘yellow submarine,’ a storm-water tunnel transformed into the ‘Nile,’ and an empty lot, ‘Die Veld,’ became their ‘Serengeti’ where they hunted imaginary lions with mop-stick spears. This imaginative play offered a vital escape from the harsh realities of apartheid.”}, {“question”: “What challenges did children face in overcrowded classrooms during apartheid?”, “answer”: “Classrooms were severely overcrowded, with up to forty-five students sharing limited resources like three sticks of chalk. Teachers often used physical discipline, and individual learning difficulties like dyslexia or ADHD were often dismissed as simply being ‘slow’ rather than receiving proper diagnosis or support. Despite these challenges, a ‘bazaar of mercy’ thrived where children secretly helped each other with schoolwork and emotional support.”}, {“question”: “How did technology and medical understanding evolve in the Cape Flats from apartheid to the present day?”, “answer”: “During apartheid, technology was scarce, with early computers like the Commodore 64 being rare contraband. Medical labels for conditions like ADHD and dyslexia were often delayed, translated poorly, and considered ‘luxury goods’ for wealthier communities. Today, fibre-optic cables crisscross the area, and children have access to 4K streaming. While medical diagnoses are more precise, the underlying social issues like violence persist. However, there’s also a growing movement towards accessible mental health support and neurodiversity awareness, even through community initiatives like ‘Ouma’s Couch’ podcasts.”}, {“question”: “What impact did the declaration of the Cape Flats as a ‘war zone’ in 1985 have on children?”, “answer”: “In 1985, the Cape Flats became a war zone with military vehicles like Buffels and Casspirs patrolling the streets. Children adapted by changing their games, for instance, playing ‘casspir-casspir’ instead of ‘cops and robbers.’ Death became a casual occurrence, and grief was often dealt with through unspoken understanding and immediate distraction, highlighting their profound resilience. They found ways to continue childhood activities like tape-ball cricket even amidst profound loss.”}, {“question”: “How is hope manifesting in the Cape Flats today, despite ongoing challenges?”, “answer”: “Hope is sprouting in various forms. Libraries now stock isiXhosa picture books that normalize therapy, and barbers offer free fades to boys who can recite suicide hotline numbers. Schools are implementing mindfulness practices like box-breathing. Even grandmothers are utilizing modern technology, hosting podcasts like ‘Ouma’s Couch’ to debunk psychiatric myths and offer community-based mental health advice, bridging traditional wisdom with contemporary platforms. These efforts show a continued spirit of resilience and adaptation, turning the ‘concrete savannah’ into a ‘launchpad’ for the future.”}]