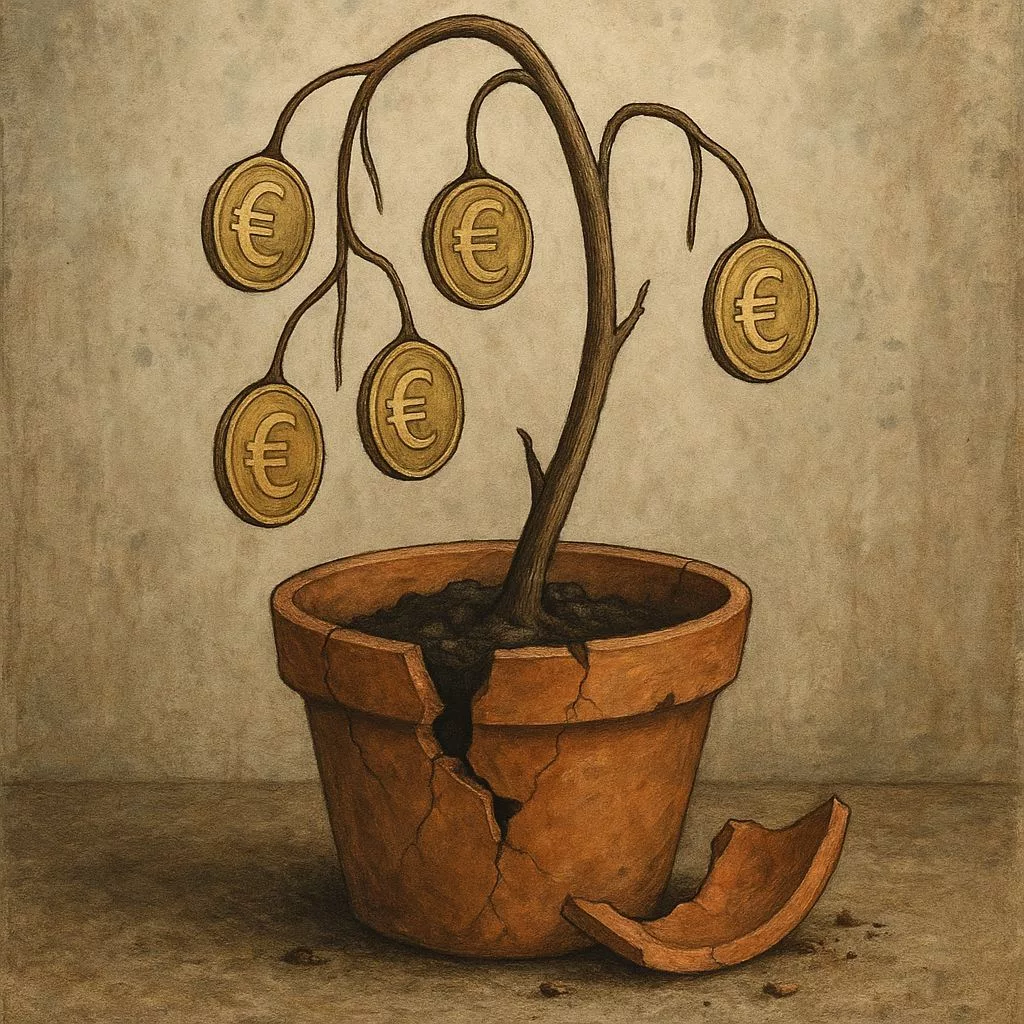

The ANC, once a powerful liberation giant, is now struggling to pay its employees. Its bank account is empty, leaving staff without salaries for months. This is happening because fewer people are paying membership fees, and the party has a lot of debt and unexpected legal bills. Even though employees are hurting, the ANC is finding it hard to get money, making payday a scary ghost story for many.

Why is the ANC struggling to pay its employees?

The ANC is struggling to pay its employees due to a significant drop in membership fees, increased short-term debt, and unplanned legal bills related to the Zondo Commission. These financial challenges, coupled with parallel campaign spending and limited avenues for fundraising, have left the party’s Luthuli House headquarters facing persistent salary delays and an empty vault.

1. Payday Becomes a Ghost Story

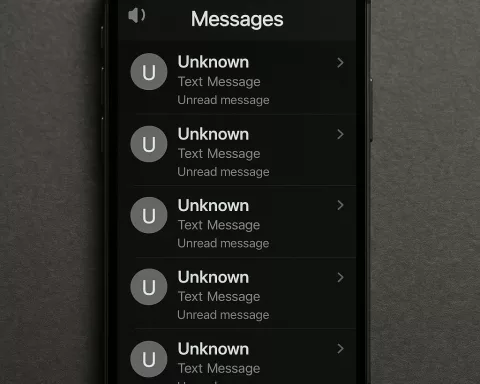

The last Friday of November was supposed to be ordinary: bank-alert pings, grocery queues, Soweto taxis filling up for the weekend. Instead, 150 ANC head-office employees stared at a two-line message from finance chief Patrick Flusk: “Your November salary will be delayed.” No date, no culprit, only the familiar line that “this default is not your fault.” Three business days later, balances still read zero.

Receptionists, researchers, the media desk and even the drivers who shuttle the party’s “Top Six” had been here before – this was the third dry month in eleven. Each time the pattern repeats: whispered assurances, a partial rescue from an overdraft extension, then another plunge. Workers say treasurer-general Gwen Ramokgopa has not addressed them since an August Zoom call that ended before questions.

The shock value is gone. In February the secretary-general himself, Fikile Mbalula, admitted publicly that his own payslip had bounced. What stings now is the uncertainty that follows every reprieve. “We celebrate too early when the money finally arrives,” an IT technician told Sunday World. “We know another hole is coming.”

2. A Payroll That Once Meant Pride, Now Means Panic

R14 million a month – that is the combined wage, medical-aid and pension bill for the nine-storey headquarters. In corporate Johannesburg it is petty cash; in liberation folklore it is the covenant that once said: “Join the struggle, the family will feed you.” Dozens on the list are ex-Robben Island prisoners, Umkhonto we Sizwe operatives or children of icons who gave up careers for “the movement.”

The unwritten contract started fraying when membership fees collapsed. Branches either rebelled against candidate lists or simply could not squeeze rands from the unemployed. Add the 2021 Electoral Commission decision to stop handing out free posters and the cash taps narrowed further. The average administrator is now 52 years old, with varsity bills and bond payments timed to a pay-cheque that no longer arrives on time.

A 59-year-old archivist, too embarrassed to give her name, fries vetkoek on a Noordgesig sidewalk every afternoon. “My neighbours still think I work for a proud organisation,” she told the Mail & Guardian. “I can’t shatter that illusion.”

3. Where the Coins Disappeared

Late, incomplete and politically sanitised numbers still tell a stark story. The 2022 audit, tabled in Parliament only in mid-2023, shows three gaping holes: membership income crawled in at R46 million against a budgeted R120 million; short-term debt climbed to R189 million, chewing R1.2 million in interest every 30 days; and Zondo-related legal bills added an unplanned R23 million as nine law firms kept their retainers ticking.

Parallel campaign spending deepened the wound. Factions pushing “renewal” or “radical economic transformation” ran WhatsApp, TikTok and community-radio blitzes that were never booked to the elections account. Those invoices are now being dumped on head-office books, shrinking the pool meant for salaries.

Insiders describe a monthly ritual: the finance team prepares a spreadsheet titled “liquidity stress,” leadership promises to cut external lawyers, then a court notice arrives in the mail and the cycle resets.

4. Magaliesburg, Merch and Mosquitoes: What Is Left to Sell?

Property agents value Luthuli House at R85 million, but FirstRand already holds a R55 million bond on the 1970s lease-hold. The party’s 300-hectare beet-and-cattle farm in Magaliesburg could bring in R28 million if rezoned for eco-lodges, yet hawks inside the alliance warn that “selling the revolution” will spark a factional war. A fleet of 42 mostly battered Toyota Quantums and one armoured Mercedes (ex-Jacob Zuma) would hardly clear R3 million at auction.

Archivists have floated the idea of monetising struggle songs, posters and documentary footage, but valuers struggle to price heritage. The laptop that once stored Nelson Mandela’s 1994 campaign schedules now sits with a mashonisa as collateral for a R5 000 loan; its encryption key has been disabled, creating a mini black market in liberation memorabilia.

5. Blocked Escape Routes and Creative Stunts

South Africa’s electoral law gives parties a once-off stipend for elections and parliamentary support, nothing more. Three rescue plans have already been vetoed: a 10 % parliamentary-caucus levy was killed by President Ramaphosa who dreaded the headline “MPs fund own party”; municipal managers in Ekurhuleni and eThekwini were quietly asked to divert electricity-surplus cash until Treasury threatened criminal charges; and a proposed R500 million Johannesburg Stock Exchange bond, backed by future state subsidies, collapsed when the 2023 budget trimmed party funding by a fifth.

Desperation is breeding ingenuity. A solidarity trip to Palestine returned with R4.3 million in donor surplus; the money was rerouted to the staff-catering account so that core payroll cash could breathe. R15 000-a-plate “Golf for Cuba” dinners are scheduled for Cape Town wine estates, promising 30 % of proceeds to “organisational maintenance” – a euphemism everyone understands.

6. Workers Fight Back – Without a Union

There is no recognised union at Luthuli House, but the self-styled ANC Employees Forum has drafted three legal letters since August. They threaten a joint CCMA case for unfair labour practice, a possible insolvency application under section 344 of the Companies Act, and a demand for 5 % interest on unpaid wages.

Harris & Co., the party’s labour lawyers, counter with grocery vouchers and the argument that “political parties enjoy special constitutional protection.” Labour attorneys call the claim shaky; the Forum continues to gather sworn affidavits and membership cards as evidence.

In the car park on Sauer Street, mashonisas idle in a white minibus offering R5 000 advances at 30 % interest over 14 days. Inside, cleaners still polish the granite lobby, security still salutes, and 24-hour news crews still wait for a sound-bite that will explain how a 112-year-old liberation movement became an employer that cannot employ.

Why is the ANC struggling to pay its employees?

The ANC is struggling to pay its employees primarily due to a significant decrease in membership fees, a substantial increase in short-term debt, and unexpected legal bills, particularly those stemming from the Zondo Commission. These financial pressures, combined with parallel campaign spending that was not properly accounted for and limited fundraising options, have led to persistent salary delays and an empty bank account at Luthuli House.

How long have salary delays been an issue for ANC employees?

Salary delays have been a recurring problem for ANC employees, with November’s delay being the third dry month in the past eleven. This consistent issue highlights a prolonged period of financial instability for the party, causing significant hardship for its staff.

What is the monthly payroll cost for the ANC headquarters?

The combined monthly cost for wages, medical aid, and pension for the approximately 150 employees at the ANC’s nine-story headquarters is R14 million. This substantial sum reflects the ongoing financial obligation the party faces, despite its current liquidity challenges.

What are the main reasons for the ANC’s financial deficit?

The ANC’s financial deficit can be attributed to several key factors: membership income in 2022 was only R46 million against a budgeted R120 million, short-term debt climbed to R189 million incurring R1.2 million in monthly interest, and unplanned legal bills related to the Zondo Commission amounted to R23 million. Additionally, unrecorded parallel campaign spending further depleted funds meant for salaries.

Has the ANC attempted to sell assets or find alternative funding?

Yes, the ANC has explored various options to generate funds. Potential asset sales include Luthuli House itself (valued at R85 million, but with a R55 million bond), and a 300-hectare farm in Magaliesburg (potentially R28 million). They also considered monetizing historical archives. Regarding funding, vetoed rescue plans included a 10% parliamentary-caucus levy, diverting municipal electricity-surplus cash, and a proposed R500 million Johannesburg Stock Exchange bond. Creative stunts include solidarity trips yielding donations and ‘Golf for Cuba’ dinners.

How are ANC employees addressing the non-payment of salaries?

ANC employees, despite lacking a recognized union, have formed the self-styled ANC Employees Forum. This forum has drafted legal letters threatening a joint CCMA case for unfair labor practice, a possible insolvency application under the Companies Act, and a demand for 5% interest on unpaid wages. They are actively gathering affidavits and membership cards to support their legal actions, pushing back against the party’s claims of special constitutional protection.