Cape Town is boiling hot in December because a big air system called the South Atlantic High moves too close. This system pushes air down, making it hot. Then, another air layer acts like a lid, trapping all that hot air. This makes the city feel super warm, much hotter than usual, causing everyone to reach for sunscreen and cold drinks.

What causes the extreme heat in Cape Town during December?

The extreme heat in Cape Town in December is primarily caused by the South Atlantic High-pressure cell sitting unusually close to the coast. This system drives air downwards, compressing and warming it. An upper-level ridge then acts like a lid, trapping the warm air and intensifying the heat.

Copper Dawn and a Mercury Chase

The sun cracks the horizon at 05:28 on Thursday, 11 December, painting a thin bronze rim along the Atlantic before it spills up the eastern flanks of Table Mountain. By seven the rooftops shine like newly pressed coins and the city is already gossiping about the 29 °C forecast. Mid-December afternoons normally linger in the mid-twenties, so a four-degree leap feels like a plot twist. Drivers top up coolant, pharmacists reorder sunscreen, and harbour fishmongers quietly add ten percent to the price of snoek; everyone knows a single scorcher can reshuffle traffic, tempers and dinner menus.

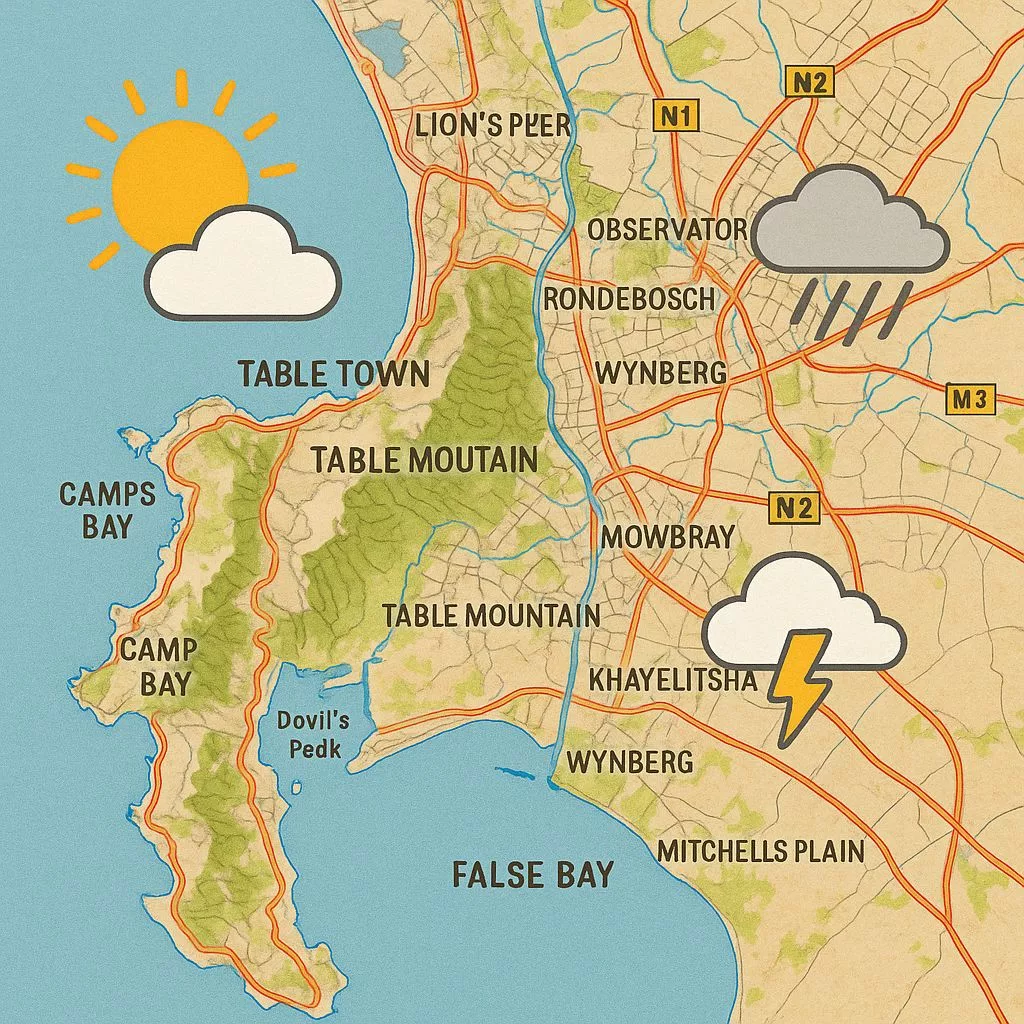

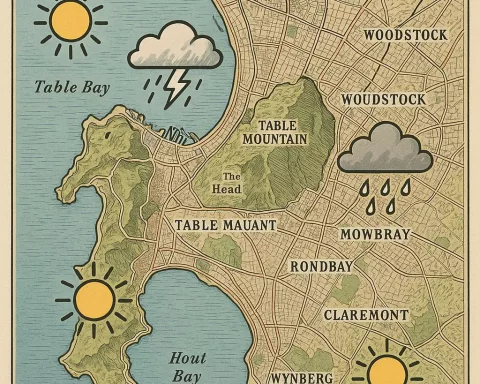

Behind the heat stands the South Atlantic High, a migrating pressure cell that usually idles 200 km farther out in the ocean. Today it has crept closer, anchoring itself just offshore. Its clockwise swirl drags air downward along the west coast, compressing and warming it at roughly one degree for every hundred metres it falls. That trick alone would push the downtown thermometer to 26 °C, but an upper-level ridge – seen on water-vapour imagery as a dark, narrow tongue – has settled over the interior. Acting like a saucepan lid, the ridge traps the low-level warmth, and by eleven the city bowl feels pre-heated, ready for roasting.

The cloud sheet tells a subtler tale than the blunt “82 % cover” figure. Stratocumulus undulatus arrives in soft, oval pads that graze the sky at roughly two kilometres. They drift on a 13 kph west-south-westerly, filtering rather than blocking light. The result is deceptive: the UV index still rockets to eight, enough to turn pale skin crimson in twelve minutes, only three minutes slower than under a cloudless sky. Queues outside Sea Point chemists stretch around the block by 09:30, every shopper clutching a bottle of SPF-50 like a talisman.

The Wind’s Sneaky Agenda

By ten the real protagonist steps onstage: the wind. The pressure gradient between the offshore high and a thermal low brewing over the Karoo tightens, and the onshore breeze surges from 13 kph to 25 kph. Funneled through the Milnerton gap, it punches the coast at 37 kph. Two kite-surfers at Blouberg watch their gear cartwheel into the surf before they can unclip, while up the west-coast road citrus growers fire up 15-metre wind machines to keep tender blossoms from drying out. Table Mountain’s north face turns into a natural gauge; dust spirals off the lower cable-station lot like upside-down waterfalls.

At fifteen hundred hours the breeze tilts thirty degrees toward the north-west, a quiet announcement that a mid-level trough is nibbling at the ridge. Sunbathers at Clifton notice nothing, but pilots landing on runway 01 feel a sudden tail-wind nudge and add five knots to their approach. In weather code, that backing wind is the opening line of a summer cold front still thirty-six hours away; tonight it will leave only the faintest calling card – high cirrus streaks that catch the dusk and turn the sky into rippled salmon silk.

Humidity behaves like a shy party guest. At dawn the city bowl lingers at a comfy %, yet once the sun climbs, the reading plummets to twenty-eight. The drop coaxes fynbos on Signal Hill to release terpenes, the rosemary-pinewax molecules that scent the air. By late afternoon the concentration is high enough to make a backyard braai in Camps Bay flare theatrically when the breeze shifts; one homeowner swears the steak finishes with a hint of protea.

Between Cool Water and Hot Asphalt

The ocean refuses to cooperate with the atmospheric bake. Three days of upwelling have left Muizenberg at 17.4 °C, a full degree below the December mean. Beach politics split along thermal lines: toddlers and British visitors huddle in rash-vests on the sandy arc, while locals trek to St James tidal pools, where dark rocks store solar heat and the water feels almost spa-like. From the air, shark-spotters count seven great whites between Strandfontein and Macassar; the cold, plankton-rich water turns the sea a pale, milky turquoise and sharpens every dorsal fin.

Back on land, concrete and tar keep soaking up rays. By five the urban core has stockpiled enough heat to stay two degrees warmer than the airport. Taxi ranks in District Six shimmer like asphalt mirages. Inside the Artscape Theatre the chillers guzzle 1.2 MW from the grid just as rooftop PV panels fade. Eskom’s control room records a 200 MW dip in demand – the “duck curve” in action – big enough to delay diesel-peakers by three-quarters of an hour. In Bellville a homeowner’s inverter clicks; lithium batteries shoulder the pool pump, and the city’s patchwork 38 MWh of distributed storage quietly hums through the evening surge.

The sun drops into the Atlantic at 19:51, yet twilight stretches for thirty-eight minutes thanks to the high cloud deck. Colour bleeds from blood-orange at the horizon to indigo overhead; Venus pops first, then Jupiter, so bright its reflection hits the Portside Tower like a second beacon. The air temperature free-falls from 27 °C to 22 °C in twenty minutes, restrained only by the slow release of latent heat from brick and tar. Outside the Grand Parade, vendors flip on battery LED strips; boerewors fat sizzles onto coals and rises as a low-level scent inversion that will linger until the wind veers after midnight.

Nightfall, Moths and a Front on the Horizon

By ten only five percent of the sky remains veiled, the last stratocumulus reduced to ghostly wisps. UV lamps above Long Street rooftop bars no longer compete with celestial glare; instead they lure moths whose wings beat soft tattoos against acrylic shields. Far above the Karoo the approaching front sketches its first high cirrus, but on the ground the city slips under a quilt of self-made warmth. Table Mountain stands ink-black against starlight, the Atlantic inhales and exhales with metronomic patience, and for a moment the wind forgets which direction it meant to blow.

Even in the dark the peninsula keeps whispering data: temperature probes on Signal Hill log a 0.3 °C micro-bump every time a taxi accelerates up Buitenkant Street; satellite receivers at the Hartebeesthoek tracking station clock a 4 % rise in atmospheric moisture as the distant trough nudges closer; and in suburban garages lithium-ion cells discharge in perfect synchrony, shaving peak demand by fractions of a kilowatt here, a kilowatt there. Every reading is a breadcrumb pointing toward tomorrow’s cold front.

For now, though, the city sleeps, lulled by the smell of fynbos, the afterglow of a copper sunrise and the promise that Friday’s south-westerly will arrive with cooler air, spitting drizzle on the promenade and flipping the meteorological script once again. Until then Cape Town keeps its windows open, its fans whirring and its dreams tuned to the hum of a wind that, for a few short hours, decided to blow indecisively from everywhere and nowhere at once.

[{“question”: “What causes the extreme heat in Cape Town during December?”, “answer”: “The extreme heat in Cape Town in December is primarily caused by the South Atlantic High-pressure cell sitting unusually close to the coast. This system drives air downwards, compressing and warming it. An upper-level ridge then acts like a lid, trapping the warm air and intensifying the heat, making the city feel much hotter than usual.”}, {“question”: “What is the significance of the South Atlantic High in Cape Town’s weather?”, “answer”: “The South Atlantic High is a migratory pressure cell that usually idles farther out in the ocean. When it creeps closer to Cape Town, it anchors offshore and its clockwise swirl drags air downward, compressing and warming it. This is a primary driver of high temperatures in the region.”}, {“question”: “How does an upper-level ridge contribute to the heat?”, “answer”: “An upper-level ridge, often seen on water-vapour imagery as a dark, narrow tongue, settles over the interior and acts like a ‘saucepan lid’. It traps the low-level warmth generated by the South Atlantic High, preventing it from dissipating and thus intensifying the heat felt in the city.”}, {“question”: “How do clouds affect the UV index during hot days in Cape Town?”, “answer”: “Even with stratocumulus undulatus clouds providing 82% cover, the UV index can still rocket to high levels (e.g., eight). These clouds filter rather than block light, meaning pale skin can still turn crimson in as little as twelve minutes, only slightly slower than under a cloudless sky. This highlights the importance of sunscreen even on seemingly overcast days.”}, {“question”: “What role does the wind play during these hot conditions?”, “answer”: “The wind, driven by the pressure gradient between the offshore high and a thermal low over the Karoo, becomes a significant factor. It can surge to high speeds, impacting activities like kite-surfing and agriculture. Later in the day, a shift in wind direction (backing wind) can signal the approach of a summer cold front, bringing cooler air.”}, {“question”: “How does the ocean temperature react to the atmospheric heat?”, “answer”: “The ocean often refuses to cooperate with the atmospheric heat. Due to upwelling, coastal water temperatures, like those in Muizenberg, can be significantly cooler than the December mean (e.g., 17.4 °C). This creates a stark contrast between cool water and hot land, influencing beach activities and even attracting marine life like great white sharks to the plankton-rich, cold waters.”}]