John Hume built the world’s largest private sanctuary for white rhinos in South Africa, hoping to save them by legally selling their horns like a renewable resource. His bold idea mixed business with conservation, drawing attention and hope. But soon, his plans were shadowed by serious legal troubles, with accusations that rhino horns were secretly smuggled to illegal markets. This sparked a fierce debate about whether treating wild animals like commodities helps or harms their survival. Hume’s story remains a powerful and complicated example of ambition clashing with the risks of exploiting nature.

What is John Hume’s legacy in rhino conservation?

John Hume created the world’s largest private white rhino sanctuary, using market-driven “conservation capitalism” to protect and sustainably harvest rhino horns. Despite initial success, his approach faced legal challenges and allegations of horn smuggling, sparking debate over private enterprise’s role in wildlife conservation.

A Vision Born on the Veld

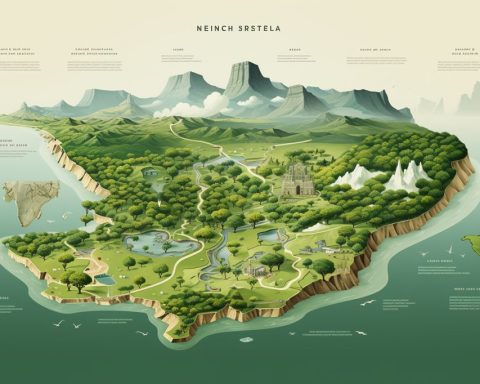

On the open plains near Klerksdorp, South Africa, the sight and sound of rhinos once offered a rare glimmer of hope for their embattled species. John Hume, a former hotelier turned conservationist, turned these grasslands into the world’s largest private sanctuary for white rhinos. Over more than a decade, his ranch became home to some 2,000 individuals – an astonishing one-eighth of the planet’s total rhino population. This achievement placed Hume at the center of a fierce debate: could private enterprise and market-driven strategies shield rhinos from extinction, or did these same forces imperil them further?

Hume cultivated an image as a pragmatic savior, fencing his property and layering it with security to protect his herd. He argued that the commercialization of rhino horn, if properly regulated, could disrupt illegal poaching by satisfying demand through legal channels. He frequently likened horn harvesting to sustainable forestry, noting that rhino horns naturally regrow and that careful management might allow humans to benefit without causing lasting harm to the animals.

This approach, which Hume called “conservation capitalism,” attracted global attention. His operation bustled with veterinarians performing horn removals under anesthesia, security teams on constant alert, and a steady stream of visitors observing what seemed an innovative merger of business and environmentalism. Yet, just as often, critics accused him of playing with fire – suggesting that the commodification of wildlife had historically led to tragedy, not salvation.

Market Logic Meets Legal Limits

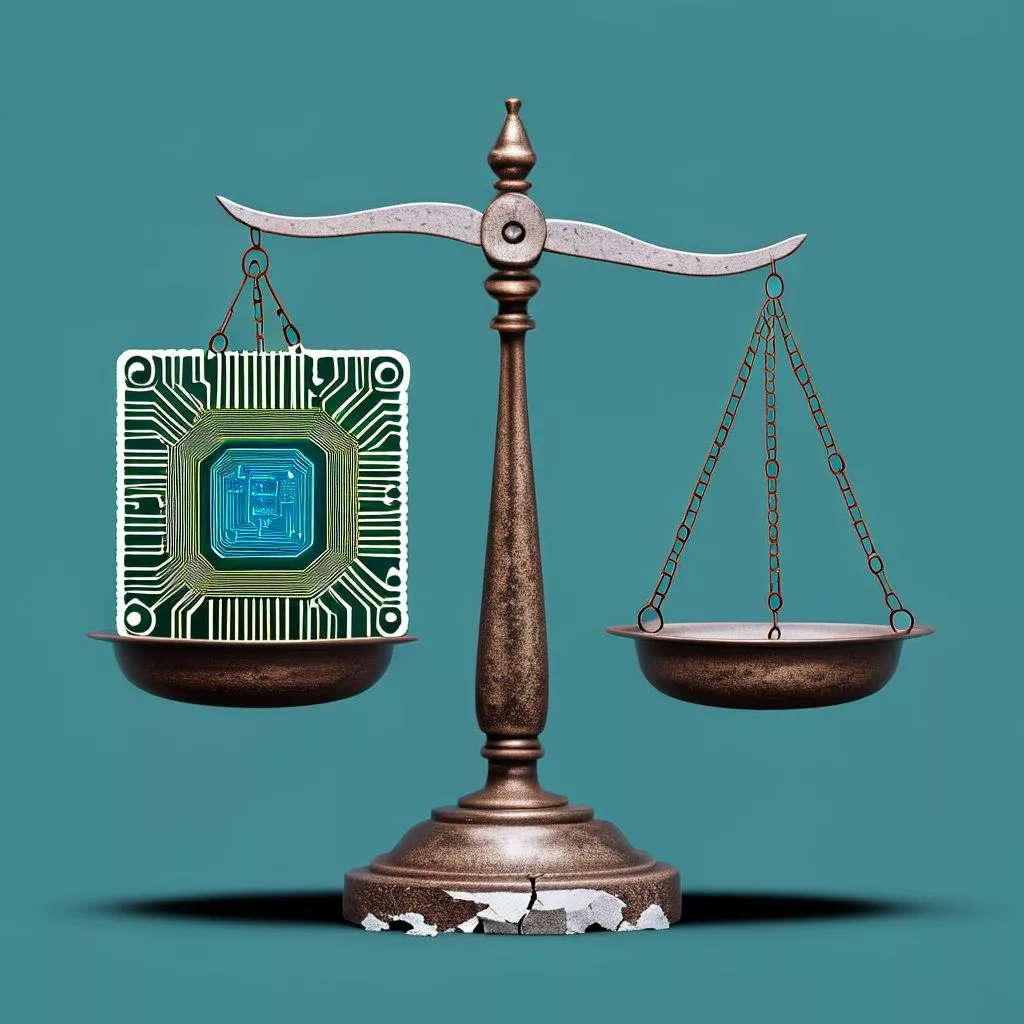

Hume’s philosophy found support among economists and policy thinkers who believed in aligning private incentives with public conservation goals. Academics from prestigious institutions in South Africa and abroad cited examples from other African countries where regulated sales of ivory appeared to aid elephant populations. These supporters argued that, by tapping into the profit motive, conservation efforts could unlock resources and innovation that government programs often lacked.

However, the international legal landscape proved far less accommodating than Hume had hoped. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) imposed a sweeping ban on commercial rhino horn exports. South Africa eventually permitted domestic trade in rhino horn after a protracted legal battle, but with virtually no local market, the regulatory gap widened. This left a tempting loophole – one that prosecutors now claim Hume and his associates exploited.

According to law enforcement, Hume’s syndicate utilized South Africa’s legal framework to mask the laundering of rhino horns destined for black-market buyers in Southeast Asia. The operation involved falsified permits, fraudulent documentation, and transactions that disguised illegal exports as legitimate domestic sales. Nearly one thousand horns, worth an estimated R250 million, reportedly vanished into the criminal underworld, where demand remains fueled by long-standing myths about rhino horn’s miraculous healing properties. These legends, especially prevalent in Vietnam and China, have persisted despite consistent scientific debunking.

Shadows and Syndicates

The cast surrounding Hume further complicates the narrative. Among those arrested alongside him are Clive Melville and Mattheus Poggenpoel, both of whom have previous convictions related to rhino horn crimes. Melville’s record includes a 2019 sentence for fraud and possession of illicit horns, while Poggenpoel pleaded guilty in 2009 to similar charges and currently faces additional accusations involving illegal ammunition and drugs. Their involvement suggests that Hume’s enterprise may have crossed a critical ethical and legal threshold.

Authorities allege that the group’s methods mirrored those of sophisticated multinational crime syndicates. They suspect the team laundered money, falsified official paperwork, and orchestrated a complex web of logistics to keep their activities hidden from law enforcement. The sheer scale of the alleged smuggling – nearly a thousand horns – echoes earlier periods in South Africa’s history, when fortunes were made and lost through gold and diamond smuggling. In each case, ambition blurred into opportunism, and the boundary between entrepreneurship and criminality grew indistinct.

This dimension of the story recalls cautionary tales from literature and history alike, where noble intentions devolve into exploitation. The parallels to Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” seem apt: ideals corrupted by greed, and lines between savior and exploiter erased by the relentless pursuit of profit.

The Debate Over Conservation’s Future

The charges against Hume have reignited fierce debates within conservation circles. Some warn that his fate illustrates the dangers of treating wildlife as mere commodities. The utilitarian logic behind market-driven conservation strategies – rooted in Enlightenment-era faith in rational self-interest – often fails when human appetites outpace nature’s capacity for renewal. History offers grim reminders: the near-extinction of the American bison and the total loss of the passenger pigeon did not result from regulatory failure alone, but from the overwhelming power of profit to drive exploitation beyond sustainable limits.

Still, Hume’s supporters counter that he devoted his life and fortune to protecting rhinos, especially when state-led efforts faltered. Former employees recall his deep personal involvement – from conducting dawn inspections to overseeing medical procedures and wrangling with bureaucrats. In their view, his actions arose from frustration with government inaction and the relentless escalation in poaching, which saw organized crime syndicates decimate wild populations, particularly in places like Kruger National Park.

For several years, data appeared to vindicate Hume’s experiment. His herd expanded, scientists flocked to the ranch to study genetics, and veterinarians refined best practices for horn removal. The ranch projected an image of enlightened stewardship, where commerce appeared to fund not just profit, but also scientific research and breeding programs that might otherwise have been impossible.

Unraveling and Uncertainty

Yet, the broader context of wildlife conservation changed rapidly. Global outrage against poaching stiffened resistance to any form of legal rhino horn trade. Non-governmental organizations launched aggressive campaigns, using graphic imagery to galvanize public opinion and pressure governments to adopt zero-tolerance policies. In this shifting landscape, legal and political setbacks mounted for Hume. Finally, in 2023, he sold his entire rhino herd and ranch to African Parks – a conservation non-profit bankrolled by European donors and aristocrats. This transfer ended a chapter in which private enterprise tried, and ultimately failed, to reconcile capitalist logic with the demands of conservation.

The fallout from these events continues to ripple through both legal and conservation communities. Hume’s legacy remains fiercely contested. Defenders argue that he attempted the near-impossible: making commerce serve the cause of species preservation. Detractors see confirmation that commodification cannot save living things from the marketplace’s inherent volatility and risk. The legal proceedings now unfolding in South African courts will determine personal culpability, but the philosophical debate they provoke runs much deeper.

As dusk settles on the South African veld, the rhinos that once symbolized Hume’s vision now graze under new stewardship. Their fate – like that of countless other endangered species – hangs in the balance, caught between competing models of protection. The fundamental question persists: how can humanity safeguard its natural heritage in a world shaped by both ambition and exploitation? The answer, as ever, remains elusive, but the urgency to resolve it grows with each passing day.

What was John Hume’s approach to rhino conservation?

John Hume pioneered a market-driven approach known as “conservation capitalism,” establishing the world’s largest private sanctuary for white rhinos in South Africa. His idea was to protect rhinos while legally harvesting and selling their horns as a renewable resource, similar to sustainable forestry. By doing so, he hoped to undercut illegal poaching by satisfying demand through regulated channels.

Why did John Hume’s rhino horn trade become controversial?

While initially seen as innovative, Hume’s operation soon faced serious legal allegations that rhino horns were smuggled illegally to black markets in Southeast Asia. Authorities accused his syndicate of falsifying permits and laundering horns under the guise of legal domestic sales. Critics argue that commodifying wildlife risks encouraging exploitation rather than preventing it.

How did international laws affect Hume’s plans?

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) bans the commercial export of rhino horn globally. Although South Africa allows domestic trade under strict rules, the lack of a local market created loopholes exploited by criminal networks. This complex legal environment limited the effectiveness of Hume’s business model and contributed to allegations of illegal horn exports.

Who were the other individuals involved, and what is their significance?

Alongside Hume, individuals such as Clive Melville and Mattheus Poggenpoel – both with prior convictions related to rhino horn crimes – were arrested. Their involvement suggests that Hume’s operation may have crossed ethical and legal lines, resembling tactics used by organized crime syndicates to smuggle and launder wildlife products.

What are the main arguments for and against treating wildlife as commodities?

Supporters of Hume’s model argue that market incentives can unlock funding, innovation, and sustainable management practices that government efforts alone may lack. Opponents caution that profit motives often outpace nature’s limits, historically leading to overexploitation and species decline, as seen with the American bison and passenger pigeon. The debate centers on whether commodifying wildlife can truly coexist with conservation goals.

What is the current status of John Hume’s rhino sanctuary and legacy?

In 2023, John Hume sold his rhino herd and sanctuary to African Parks, a non-profit conservation organization. This marked an end to his experiment with private enterprise-driven conservation. His legacy remains deeply contested: some view him as a visionary innovator who challenged the status quo, while others see his downfall as evidence that wildlife commodification poses serious risks. Legal proceedings against him continue, but the broader philosophical debate about conservation’s future persists.