South Africa is facing a terrible shortage of rape kits, which stops justice for survivors. This is because of slow paperwork, problems with getting supplies, and kits donated from other countries sitting unused. Without these kits, doctors can’t collect important evidence, making it impossible to catch attackers. This sad situation means many cases are closed, and survivors don’t get the justice they deserve.

Why is there a shortage of rape kits in South Africa?

South Africa faces a critical shortage of rape kits due to procurement delays, bureaucratic hurdles, and inefficient supply chain management. Orders are stalled by re-categorization demands and credit-gate issues, while donated kits remain unused due to import-exemption requirements, severely impacting justice for survivors.

- A front-line chronicle stitched together in Epping’s echoing depot, on clinic tiles, and inside the silent detours survivors are forced to endure.*

1. Doors Roll Up, Hope Rolls Down

No press notice warned the guards that Members of Parliament would appear at 07:30 sharp outside the SAPS depot in Epping Industria. Coffee still steamed in styrofoam when the roller-gates clattered open “for a routine look-around.” Neon tubes buzzed above a hangar-sized floor built for air-freight pallets; instead, row after row of shrink-wrapped concrete slabs stood naked – labels intact, contents missing. Within six minutes the inventory boss conceded the obvious: not one adult D1 kit, not one child-size D7, remained.

The SAPS 13 ledger told the rest: final D1 box signed out 28 October; final D7 three days later. Since that Halloween shift, 412 Western Cape survivors had opened cases stamped “forensic samples pending – kits unavailable.” Paper promises, nothing more.

A guard kicked an empty pallet; the hollow knock echoed like a starting pistol for every subsequent failure in the chain.

2. Why a Cardboard Carton Beats a Clinician’s Best Intentions

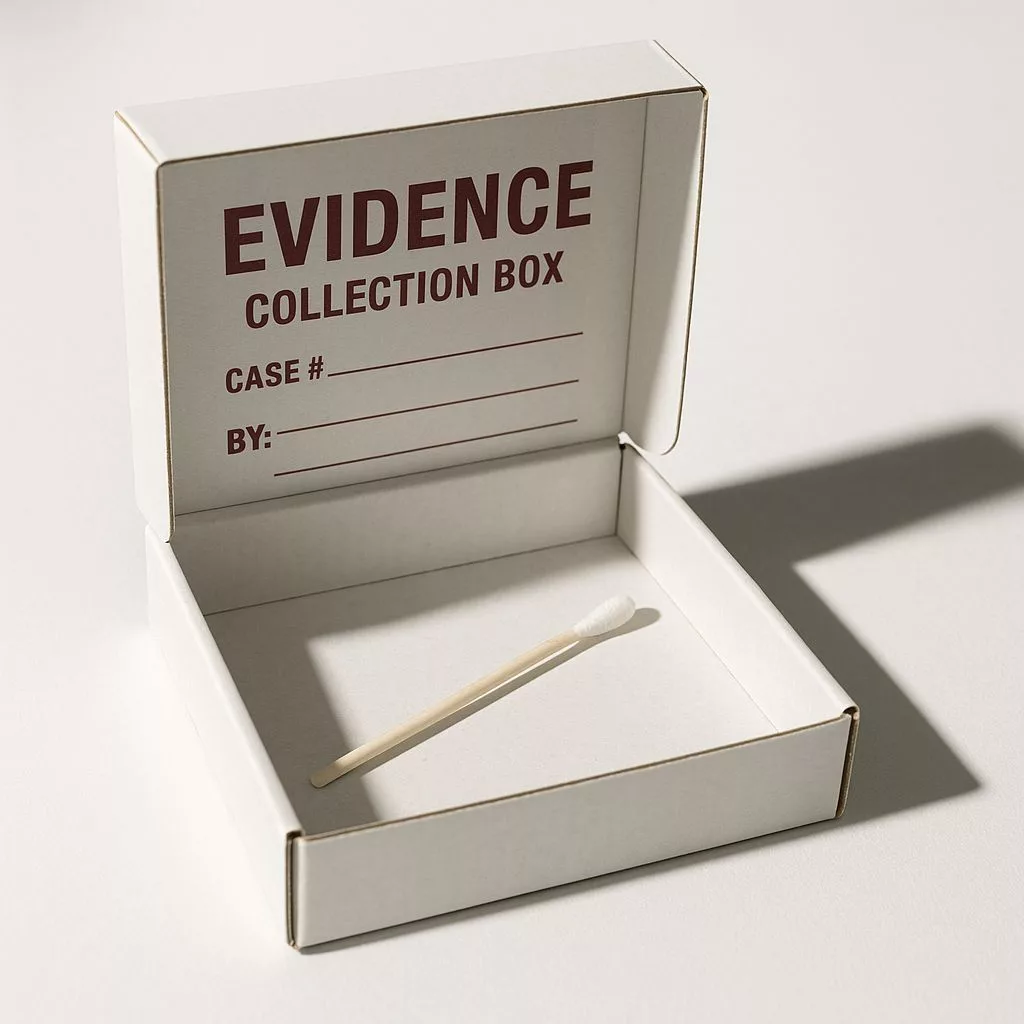

Strip away the tape and you find thirty-four bar-coded tools: knee-length paper sheets to catch stray fibres, twin combs for head and pubic hair, a dozen sterile swabs split between moist and dry stains, three blood tubes colour-coded for chemistry, micro-slides, nail-parings pouches, buccal swabs, tamper-evident tape, plus the consent form whose counterfoil is the first link to a courtroom.

Swap the D1 for a D7 and you get kid-friendly diagrams, smaller specula, and a foil blister of PEP dosed for a 25-kilo body. Every item carries a Lot number that can be walked back to an autoclave print-out in Germany or India; that traceability is what defence counsel grill over when contamination is alleged.

A doctor can stitch tears, dispense antiretrovirals, chart bruises on a body map – but without those cotton-tipped sticks the biological bridge between survivor and suspect rots within seventy-two hours. The investigation capsizes at step one.

3. A Pipeline Designed to Drip, Not Flow

Manufacture sits with two ISO-accredited plants – Durban and Pretoria – under a 2022 framework that vows “rolling thirty-day cover at 75 % burn rate,” bureaucrat-speak for a three-month cushion. Yet provinces cannot ring the factory; they e-mail a SAPS 275 wish-list to Pretoria’s Supply Chain Management. Western Cape analysts, watching December’s five-year spike, begged for 3 200 adult and 1 100 paediatric kits on 18 September. By early December the order had not even cleared Treasury’s new credit-gate. A re-categorisation demanded a fresh bank guarantee; the shuffle froze the province for nine weeks while assaults did not take a single day off.

National Treasury’s envelope lists R1.2 billion for “medical forensic supplies” – autopsy sutures, booze kits, paternity tests all swimming in the same bucket. Activists calculate full rape-kit coverage would siphon off R42 million, 3.5 % of the line. Nobody owns the budget; it drifts between SAPS, Health and Treasury like a hot potato dipped in red tape.

An NGO-chartered plane stuffed with 18 000 donated kits sat on the Waterkloof tarmac on 30 November. A late-night Treasury stop-order demanded an import-exemption only the SAPS Director-General can sign; he was reportedly “unreachable.” The fuel slot lapsed, pallets slid back into Hangar 3, and shrink-wrap still glints under floodlights while officials argue whether accepting charity amounts to “irregular expenditure.”

4. When the Swabs Never Arrive, the Law Grinds to a Halt

Picture the choreography after midnight: a teenager stumbles into a satellite police station; a constable opens CAS 480/12/2023, phones the district surgeon; the on-call locum drives 120 km to find a locker yawning bare. She can still offer PEP, a morning-after tablet, thirty minutes of trauma counselling – but the semen that could name the attacker slips past the 72-hour deadline while the docket races toward the 48-hour hand-in rule.

Up the ladder, the SVSO detective files a one-page summary: “Allegation of rape. No biological specimens.” The prosecutor sends it back for “further investigation,” code for indefinite limbo. At day 90 an SMS lands in the survivor’s inbox: “Case closed pending new leads.”

Nurses in Khayelitsha now bisect single kits – high-yield orifices only – turning one box into two. Detectives from Beaufort West clock 480 km to Kimberley to beg sister provinces for stock; defence lawyers later feast on chain-of-custody gaps. One Cape Flats mother froze an expired D7 in her kitchen; when a private doctor reopened the child, he sealed the swabs with supermarket cling-film because the evidence tape was missing. The detective accepted the bundle “under protest,” already rehearsing the cross-examination that will shred it.

Researchers extrapolate that 74 of the 412 November cases may already be fatally wounded; another 92 survivors simply never came back after hearing “no kits,” joining the invisible ledger of secondary attrition. Multiply that by nine provinces and the funnel widens into an abyss.

5. A Glimmer of Fixes – And the Clock That Keeps Ticking

Elsewhere, work-arounds breathe: Masimanyane in the Eastern Cape buys its own stock and invoices the province within ninety days; a WhatsApp group of 127 nurses posts shelf-selfies so cops can reroute survivors before the first tear falls; UCT chemists are 3-D printing bar-coded tubes that could shave 40 % off cost and dodge import gridlock.

Chile wrote a simpler ending: every clinic keeps kits under the health department’s lock; when inventory drops below fifteen, an overnight courier refills from the national lab at US $2.30 per survivor. Conviction rates climbed eleven percent in two years. South Africa’s own National Forensic Oversight Board has begged since 2018 for rapid-DNA printers that deliver a profile in ninety minutes, yet the Criminal Procedure Act still insists on cardboard continuity; the amendment bill has idled 1 084 days.

Parliament reconvenes 6 February. SAPS has seven working days to table a rescue plan; fail and the Speaker may subpoena the National Commissioner for the first time since 1997. A constitutional court bid is being drafted, arguing that stock-outs violate Section 12: the right to bodily integrity and State protection from violence. A structural interdict could force monthly sworn procurement returns – court-monitored shopping lists.

Until the pallets rise, every survivor who walks into a Western Cape charge office gambles on a 72-hour stopwatch the state cannot see. The cotton swab is 10 cm long and costs less than a loaf of bread, yet its absence stretches from the warehouse floor to the courtroom roof, drowning names, faces and futures in a silence no policy speech can fill.

Why is there a severe shortage of rape kits in South Africa?

South Africa is experiencing a critical shortage of rape kits due to a combination of bureaucratic inefficiencies, procurement delays, and supply chain mismanagement. This includes issues like re-categorization demands, credit-gate problems delaying orders, and donated kits sitting unused because of import-exemption requirements. These systemic failures prevent the timely acquisition and distribution of essential forensic tools.

What are the main components of a rape kit and why are they crucial?

A standard rape kit, such as the D1 for adults or D7 for children, contains approximately thirty-four bar-coded tools. These include sterile swabs for collecting biological samples, blood tubes, micro-slides, nail-paring pouches, buccal swabs, and tamper-evident tape, along with consent forms. Each item has a unique Lot number for traceability. These tools are crucial because they allow for the collection of vital physical evidence (like semen or fibers) within 72 hours, which is essential to link a survivor to an attacker and provide irrefutable evidence in court. Without them, investigations often collapse at the first stage.

How does the procurement process contribute to the shortage?

The procurement process is highly centralized and inefficient. Provinces cannot directly order from manufacturers; instead, they must send wish-lists to Pretoria’s Supply Chain Management. Orders face delays, such as those caused by Treasury’s ‘credit-gate’ requiring fresh bank guarantees for re-categorized items. This bureaucratic red tape can freeze orders for weeks or months, during which time assaults continue, exacerbating the shortage. The budget for ‘medical forensic supplies’ is also pooled, meaning rape kits compete for funds with other medical items, and no single entity ‘owns’ the budget for rape kits, leading to a lack of accountability.

What happens when a rape kit is unavailable for a survivor?

When a rape kit is unavailable, the collection of crucial biological evidence within the critical 72-hour window becomes impossible. While medical professionals can still offer emergency contraception, HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and trauma counseling, the lack of forensic evidence means the investigation is severely hampered. Cases may be filed as “forensic samples pending – kits unavailable,” often leading to their closure due to lack of leads. This denies survivors justice and allows perpetrators to evade prosecution. Some desperate measures include nurses bisecting kits or detectives traveling long distances to borrow stock, leading to chain-of-custody issues that can compromise evidence in court.

Are there any proposed solutions or workarounds to address the crisis?

Yes, several solutions and workarounds are being explored. Some NGOs, like Masimanyane, purchase their own stock. A WhatsApp group helps nurses share information about available kits to redirect survivors. UCT chemists are researching 3-D printing bar-coded tubes to reduce costs and avoid import delays. Other countries, like Chile, have simpler, more efficient systems for kit distribution. There are also calls for rapid-DNA printers to speed up analysis, an amendment to the Criminal Procedure Act, and a potential constitutional court bid arguing that stock-outs violate the right to bodily integrity, which could force court-monitored procurement returns.

Why are donated rape kits not being utilized?

Donated rape kits, even those arriving by chartered planes, often remain unused due to bureaucratic hurdles. For instance, a plane carrying 18,000 donated kits was reportedly grounded because of a late-night Treasury stop-order demanding an import-exemption. This exemption required the signature of the SAPS Director-General, who was reportedly unreachable. Such administrative obstacles, coupled with arguments over whether accepting charity constitutes “irregular expenditure,” prevent these much-needed kits from reaching the facilities where they are desperately needed, despite the urgent crisis.