African ministers met for breakfast, but it was no ordinary meal. They turned a simple pastry table into a war-room, fighting for Africa’s climate future. They need a lot more money for climate projects, about $50 billion each year. The ministers found $27 billion worth of projects that are ready to go, like green bonds and special funds. These projects aim to fix big problems like floods and droughts, proving that climate action is also about saving money and lives, not just the planet.

What is Africa’s climate finance gap and what solutions are being proposed?

Africa faces a significant climate finance gap, receiving only USD 19 billion annually while needing USD 50 billion by 2050 for adaptation. Ministers proposed USD 27 billion in ready-to-go projects, including green bonds, resilience funds, and innovative financing tied to environmental and social outcomes, to bridge this critical funding deficit.

The Croissant Calculus: From USD 19 Billion to a USD 50 Billion Cliff

While diplomats in the main halls of the UN Environment Assembly traded bracketed text, a smaller, fiercer math class convened over coffee. African environment bosses hunched around a linen-draped table at the UNON Complex, racing cyclone seasons, debt calendars and harvest failures that refuse to wait for another communiqué. They had come to turn the G20’s glittering promises – hammered out three months earlier under South Africa’s presidency – into balance-sheet facts for 54 nations whose joint carbon footprint is still lighter than any single OECD member.

The numbers on the napkins were merciless. The entire continent scrapes together roughly USD 19 billion a year in climate money – less than 3 % of the global pot – yet the UN Environment Programme now clocks Africa’s adaptation bill at USD 50 billion a year by 2050. In 2024 alone, governments will ship USD 74 billion offshore to service sovereign debt, four times what they receive to cool the planet. A single cloudburst in KwaZulu-Natal can lop 1 % off South Africa’s GDP in two days; last year’s Horn drought shoved four million herders below the USD 2.15 poverty line. Adaptation, ministers agreed, is no longer a line in the environment budget – it is macro policy with a hard hat.

Color-coded spreadsheets replaced polite speeches. Each row translated a floodplain, a drought corridor or a brown-coal plant into lost GDP, lost tax, lost jobs. The breakfast crowd swapped horror stories like trading cards: a port in Ghana silting up faster than dredgers can dig, a hydropower dam in Zambia dropping below turbine minimum before the bond coupon is even paid. By the time the jam pots were empty, the pastry table had become a balance-sheet battlefield where only projects that could outrun debt clocks and storm clouds deserved a seat.

Shovels, Not Slides: USD 27 Billion of Ready-to-Go Deals

Kenya’s Cabinet Secretary flipped open a laptop and live-streamed a dashboard of 46 “oven-hot” ventures – mangrove belts along the Tana, electric-bus lanes across Nairobi, micro-reservoirs in Kitui – tagged at USD 2.8 billion and able to avert USD 9.4 billion in flood damages plus carbon cash over fifteen years. Ghana countered with a USD 550 million green-bond recipe that folds cocoa-sector escrow, sovereign guarantees and rainfall-index insurance into one security. Investors earn a coupon that drops 35 basis points every year Accra’s air stays cleaner than the WHO interim target, elegantly marrying profit to public lungs.

Ethiopia floated a “resilience-for-resettlement” swap: development banks front USD 600 million to restore drought-battered watersheds and wire off-grid solar to displaced highlanders; in return they scoop future carbon credits under the COP28 Article 6.4 rulebook. Thirty percent of those credits are ring-fenced for host villages, a poison-pill clause against land-grab labels. The pitch landed hard because 4.6 million Ethiopians are already on the move, and every new refugee camp is a fiscal sinkhole that bond markets notice.

South Africa’s DBSA handed round a term-sheet for a Pan-African Resilience Finance Facility that bundles small adaptation tickets into USD 250 million parcels big enough for global pension funds. Nigeria’s NSIA and Botswana’s Pula Fund will eat the first-loss slice, flipping the old script that treats Africa as a borrower to be policed rather than a partner to be cushioned. A clever “debt-pause” clause freezes principal if the IMF declares a disaster, ensuring that a hurricane does not automatically morph into a default. By the time the orange juice ran out, the project pile hit USD 27 billion, each deal stamped with cash-flow models, escrow routes and gender-weighted impact metrics.

Beyond Megawatts: 160 GW, Hydrogen Grids and Garbage Bonds

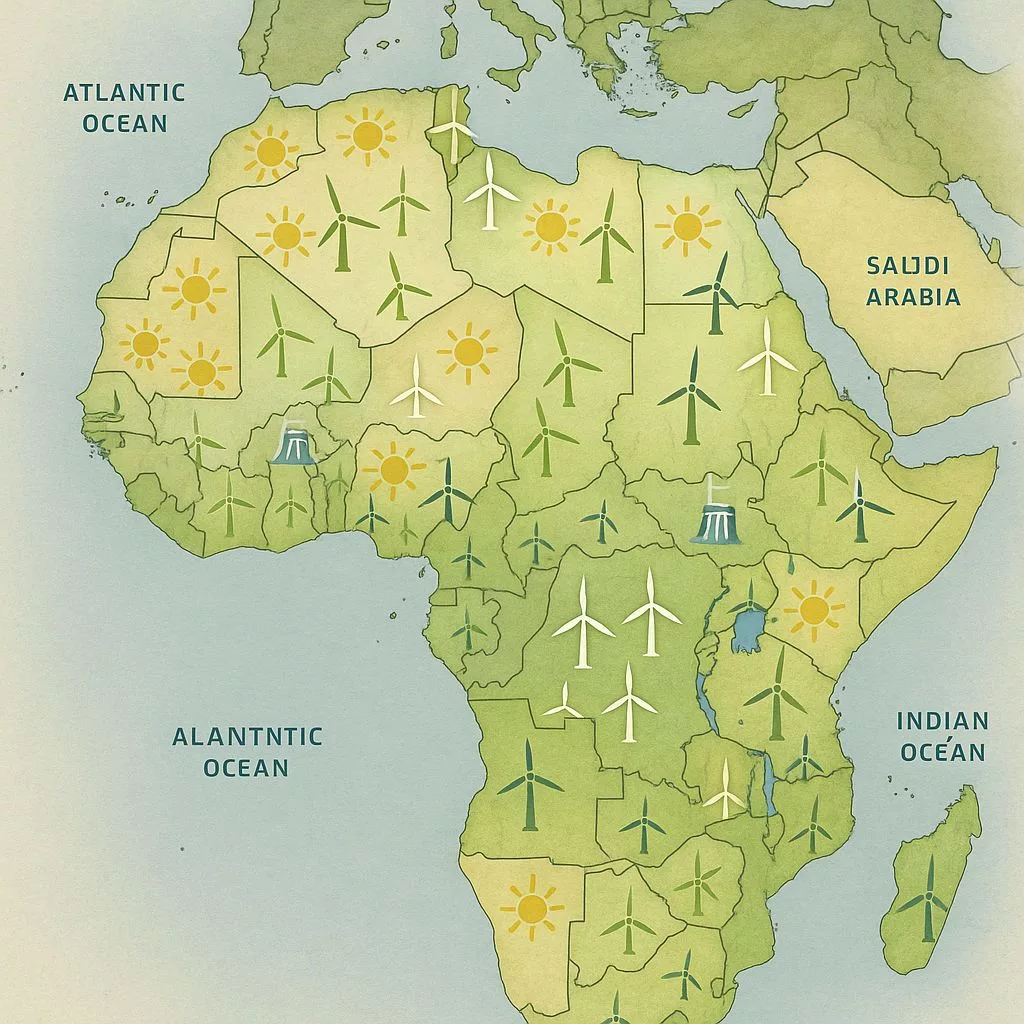

Uganda’s energy chief dismissed the fashionable “triple-renewables” mantra as kindergarten maths. Overnight modellers showed that universal access by 2030 demands 160 GW of new juice – eight times today’s installed base – of which 60 % must ride on rooftop solar and green-hydrogen micro-grids because legacy copper networks leak 18 % of every electron. Price tag: USD 350 billion. To unlock that, Uganda and Namibia drafted an African Green Hydrogen Bond Standard that clones Europe’s upcoming green-bond rulebook but grafts on a “just-transition score” weighted by how many female-headed households finally ditch charcoal for clean cooking. London Stock Exchange and Johannesburg bourse are already beta-testing disclosure templates so traders can price gender impact alongside basis points.

Waste got its moment in the sun when Rwanda’s minister dropped a stat that open garbage fires spew 13 % of Africa’s black-carbon footprint – equal to every cargo ship on the planet – yet only three capitals own engineered landfills. She circulated a draft statute that ties import duties to packaging recyclability, forcing brands to finance Extended Producer Responsibility or pay for the privilege of trash. A USD 200 million blended-finance window from the AfDB’s Sustainable Waste Infrastructure Trust sweetens the deal with 2 % loans for any city that locks in a decade of feedstock contracts with local recycling start-ups. Early models show 9 million tonnes diverted from dumps by 2030 and 300 000 informal jobs, a lifeline for ministers staring at youth unemployment north of 40 %.

Air quality – long the Cinderella no one invited – crashed the party. South Africa’s air-quality chief beamed up live data from NASA’s MAIA satellite married to sensors nailed to township schools. Since Eskom began decommissioning 8.4 GW of clunker coal, national PM2.5 has dropped 4 µg/m³, saving 650 lives and USD 190 million in health bills. Those numbers now sit in Treasury’s ledger as ammunition against lobbyists pushing a new 3 GW coal unit in Mpumalanga. Delegates from Lagos and Accra – where PM2.5 routinely tops 100 µg/m³ – begged for the open-source code, eager to replicate the life-and-death spreadsheet in their own backyards.

Smart Contracts, Crime Chains and a 90-Day Countdown

Coffee cups flew aside when Egypt demoed the “Africa Loss-and-Damage Ledger,” a blockchain that logs extreme weather every fifteen minutes from 4 000 automated stations. A verified flood or drought instantly pings the new Loss-and-Damage Fund, cutting claim-time from months to days. Alexandria pilots show payout costs down 22 % because satellite proof kills paperwork. Governance tokens split 50-50 between national weather services and community NGOs, so efficiency does not edge out local voices.

Crime disguised as commerce – illegal rosewood, pangolin scales, toxic sludge – drains Africa of USD 200 billion a year, double official aid. Ministers green-lit an expansion of the FATF “golden thread” rule, reclassifying environmental contraband as money-laundering predicates. Interpol and UNODC will embed customs agents in Mombasa and Dar with blockchain cargo-trackers that hash bill-of-lading data, making forgery a fool’s errand. A USD 50 million seed cheque from the Global Environment Facility kicks off the pilot; the end-game is a mandatory due-diligence gate for every box that leaves an African port, mirroring the EU’s incoming deforestation-free law.

Gender, once a conference garnish, was soldered into every tranche. Zambia’s Women-in-Renewable-Energy facility reserves 30 % of subordinated debt for firms run by female CEOs, betting on data that mini-grids led by women crash 45 % less often because they spend more on customer care. The target is 5 million last-mile consumers by 2028 and 1.2 billion hours freed from fuel-wood drudgery, a time gift worth USD 3.4 billion in forgone schooling and income.

As the clock struck noon, ministers inked a three-step delivery pact. Within 90 days the USD 27 billion pipeline lands at the G20’s Project Preparation Facility hosted by the AfDB. Before COP30 opens in Belém, at least 40 % must be covered by firm commitment letters – green bonds, DFIs, private equity, whatever works. By December 2025 every loan must carry outcome-based triggers: hectares of mangrove, households with clean stoves, micrograms of PM2.5 erased. Spreadsheets signed, they stepped into the Nairobi sun where Kenya’s silent electric buses slid past, proof that the prototype already hums. The only question left is whether the breakfast deals can move faster than the storm clouds now stacking over the Indian Ocean, visible from the cafeteria window and racing toward the next balance-sheet deadline.

What was the purpose of the breakfast meeting in Nairobi?

African ministers gathered for a breakfast meeting in Nairobi, which quickly transformed into a “war-room.” The primary purpose was to strategize and mobilize significantly more financing for climate projects across Africa, addressing the continent’s climate future and its substantial funding gap.

What is Africa’s current climate finance gap and its projected needs?

Currently, Africa receives only about USD 19 billion annually for climate initiatives. However, the UN Environment Programme estimates that Africa’s adaptation bill alone will reach USD 50 billion per year by 2050. This highlights a critical and growing climate finance gap.

What solutions and ready-to-go projects were identified during the meeting?

The ministers identified USD 27 billion worth of ready-to-go projects. These include innovative financing mechanisms like green bonds (e.g., Ghana’s cocoa-sector green bond), resilience funds (e.g., South Africa’s Pan-African Resilience Finance Facility), and projects tied to environmental and social outcomes. Examples include mangrove restoration in Kenya, electric-bus lanes, and off-grid solar solutions.

How are some of these proposed projects innovating climate finance?

Several projects showcased innovative approaches. Ghana’s green bond, for instance, links coupon payments to air quality improvements. Ethiopia proposed a “resilience-for-resettlement” swap, funding watershed restoration and solar for displaced communities in exchange for future carbon credits. The Pan-African Resilience Finance Facility bundles smaller adaptation projects for global pension funds and includes a “debt-pause” clause during disasters.

Beyond traditional climate projects, what other sectors were discussed for climate action?

The discussions extended beyond traditional climate projects to include universal energy access, targeting 160 GW of new capacity by 2030, with a focus on rooftop solar and green-hydrogen micro-grids. Waste management was also highlighted, with proposals for tying import duties to packaging recyclability and creating blended-finance windows for sustainable waste infrastructure. Air quality improvements, such as South Africa’s coal plant decommissioning, were also presented as having significant health and economic benefits.

How are accountability and transparency being integrated into Africa’s climate initiatives?

Ministers emphasized accountability and transparency through several mechanisms. Egypt demoed an “Africa Loss-and-Damage Ledger” using blockchain to track extreme weather events and expedite payouts from the Loss-and-Damage Fund. There’s also a move to reclassify environmental contraband as money-laundering predicates, using blockchain cargo-trackers to combat illegal trade. Furthermore, gender impact is being integrated, with initiatives like Zambia’s Women-in-Renewable-Energy facility reserving debt for female-led firms.