Even though it’s December and many are on holiday, South Africa’s Parliament is still hard at work in Cape Town. A small group of people virtually decides how billions of rand will be shared between provinces and cities. This is called DORA, and it’s super important because it’s the last chance to move money around for things like hospitals and schools. They argue a lot over who gets what, because every rand counts, and they have to finish before a deadline.

What is the Division of Revenue Amendment Bill (DORA)?

DORA is South Africa’s crucial annual legislation that reallocates existing national funds among provinces and municipalities. It is the final opportunity to adjust the budget, balancing needs like disaster relief, healthcare, and education by shifting funds, as no new money can be created.

The Coastal Campus That Never Switches Off

Long after the N2 fills with holiday-bound sedans and the first mangoes appear on street stalls, the red-brick complex on Plein Street stays lit. Coffee percolators keep burbling in near-empty passages, Wi-Fi routers flicker like deserted traffic lights, and a salt-laden southeaster rattles flag ropes above the main stairway. This is Parliament’s “dark-mode” fortnight – an eerie but scheduled ritual that arrives every December. The 400-seat National Assembly has already fanned out to constituencies, yet the 90-member National Council of Provinces still has constitutional homework: approving the 2025 Division of Revenue Amendment Bill, universally shortened to “DORA.”

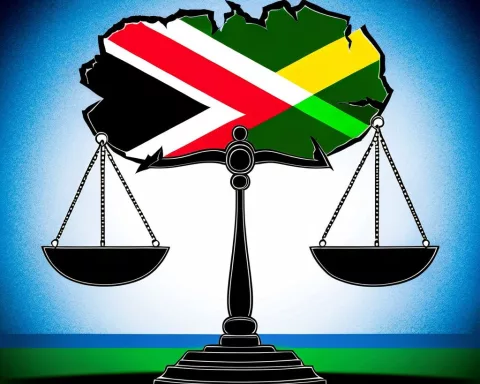

DORA looks dull on paper, but it is the last legal chance to shuffle the fiscal pack. The original Act was signed in February, yet by November the Treasury almost always finds fresh holes – currency slumps, unexpected debt-service spikes, or a department that suddenly “remembers” a multi-billion-rand contract inked in silence. Because South Africa’s money bills are zero-sum, Parliament cannot magic up extra cash; it can only nudge existing slices. Rural ambulances, library assistants, school nutrition, provincial road gangs – each stands to gain or lose in the blink of a committee vote.

While tourists photograph the Company’s Garden jacarandas, inside the precinct the stakes are measured in rands and in time. The NCOP has barely 48 hours between Monday’s select-committee vote and Wednesday’s plenary. If delegates miss the 20 December statutory printing deadline, the Finance Minister must invoke an emergency procurement clause – lawful yet politically radioactive – so every decimal point is fought over like gold dust.

The Amendment Bill Nobody Can Afford to Ignore

DORA is the third and final lap of the annual budget relay. Any new rand that appears on a provincial spreadsheet has to be counter-balanced by a rand deleted somewhere else; the pie stays the same size, only the slices move. Constitutionally the NCOP may accept, reject or tweak the Bill, yet rejection fires up a mediation process that could freeze billions earmarked for provinces already living invoice-to-invoice. In reality the Council almost always nods through Treasury’s plan, but only after a bruising 48-hour lobbying blitz.

WhatsApp groups light up with spreadsheets titled “EC – SONA cuts vs DORA upside.” Premiers who never text suddenly trade pleading-face emojis. Provincial treasuries hire retired budget specialists at R5,000 a day to craft slide-decks proving why an 0.8% tweak in the health-equity index is “non-negotiable.” One former KwaZulu-Natal official famously swung R400 million by convincing parliamentary researchers that April’s flood damage had lifted his province’s poverty score by 1.3 index points – satellite shots of submerged cane fields included.

Monday noon is decision zero. Nine delegates – one from each province – gather on Teams for the Select Committee on Appropriations. The chair screen-shares a 42-slide pack; slide 17 carries a heat-map of winners and losers. Gauteng and the Western Cape traditionally bleed points because their own tax bases look healthier, while Eastern Cape and Limpopo gain. The 2025 twist is a R5.8 billion disaster-relief pot for KZN roads, creating a fresh zero-sum war. Argue too long and the Bill overshoots the print deadline; Treasury then pulls the emergency cord and Parliament is sidelined. No delegate wants that headline, so compromise arrives in the final minutes, usually whispered through a muted phone.

Wednesday’s Virtual Stage and the Theatre Beneath It

At 10:00 sharp on 18 December the NCOP plenary opens on Microsoft Teams, the platform adopted after Zoom once booted the House mid-debate. Delegates beam in from lounges adorned with Zulu shields, Afrikaans psalters or family Christmas trees – an accidental ethnography for anyone bored by the balance sheet. The Speaker begins with farewell speeches: some syrupy, others blade-sharp. EFF proxies bewail “austerity that garrottes the poor,” ANC speakers laud “prudence that steers us from junk,” while the DA frets about “unfunded mandates shoved onto councils.”

Yet the real wrangling is already in the rear-view mirror. These orations are audition tapes for 2026’s local-government elections: a provincial back-bencher who lands a quotable line on textbook under-funding can expect WhatsApp forwards from ward councillors scouting mayoral candidates. Public deliberation, however patchy the Wi-Fi, doubles as internal party marketing. Still, the requirement that sittings be open to citizens is technically met: anyone can click the virtual-gallery link, even if December’s audience is usually one intern and a journalist scrolling for gift ideas.

Behind the screen a skeleton crew keeps the engine humming. Table clerks clock in at 06:00 to scan every schedule into the digital repository; a single malicious swap could divert billions. Interpreters work 30-minute shifts, stretching vowels so “adjusted appropriation” does not morph into “justice appropriation.” In the basement a 1997 offset printer nicknamed “Die Hard” spits 312 bound copies at R7.21 a page – more than R180,000 in toner and paper. Environmentalists protest; Parliament installs a recycling bin, then locks the security gate at 19:00 so no one can reach it.

Thursday’s Rear-View Reports and the Calendar That Never Ends

While the NCOP polishes DORA, the National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Appropriations must still adopt three reports: the 2025 MTBPS review, the Adjustment Appropriation Bill (two separate bills share the same name, distinguished only by annexure letters). This session, scheduled for 09:00 on 19 December, ratifies Treasury’s November numbers and dispatches them to the Auditor-General. Opposition parties use the slot to lodge minority opinions that live forever in the parliamentary archive. In 2023 the DA released a 14-page dissent accusing Treasury of “budgetary sleight-of-hand” to bankroll the wage bill; Moody’s later quoted that document in a credit opinion.

Watch for 2025’s controversy magnets: a R2.3 billion “unallocated” line Treasury refuses to detail, plus the sudden appearance of R950 million for “Presidential employment stimulus – phase III,” a programme whose Phase II results have never surfaced. Once adopted, these reports close the formal ledger for the year – yet they also pre-load next year’s battles. The Speaker must table the draft 2026 annual programme by 15 January; whips need to know if February’s State of the Nation Address will clash with African Continental Free Trade Area festivities. Committee chairs angle for larger offices; veteran MPs angle for overnight oversight trips that fatten pensionable service days.

Within 48 hours Parliament’s website will publish the DORA Amendment, but the document instantly begins a second life. Provincial treasuries have until 31 January 2026 to table their own adjustments; councils must align 2026/27 integrated development plans by 31 March, even though upcoming local-government elections may redraw ward maps. The Auditor-General has already pencilled 14 March 2026 for the first compliance hearing – a date booked before the Bill is law. In the foyer an antique clock minus its 2018 bell keeps ticking, reminding staff that in South Africa’s legislative machinery the December recess is simply another gear that never stops turning.

[{“question”: “

What is DORA and why is it important?

\n

DORA, which stands for the Division of Revenue Amendment Bill, is South Africa’s crucial annual legislation that reallocates existing national funds among provinces and municipalities. It’s incredibly important because it’s the final opportunity to adjust the budget for the year, balancing essential needs like disaster relief, healthcare, and education by shifting funds. No new money can be created at this stage; Parliament can only reallocate existing resources. Without DORA, critical services and projects might not receive the necessary funding.

\n”,”answer”: “”},{“question”: “

Why is Parliament still working in December, even during the holidays?

\n

Even though December is a time when many South Africans are on holiday, Parliament in Cape Town remains operational, particularly for the approval of the Division of Revenue Amendment Bill (DORA). This is referred to as Parliament’s \”dark-mode\” fortnight. The 90-member National Council of Provinces (NCOP) has the constitutional responsibility to approve DORA before a strict statutory printing deadline, usually around December 20th. Missing this deadline would necessitate the Finance Minister invoking an emergency procurement clause, which is lawful but politically sensitive.

\n”,”answer”: “”},{“question”: “

How does DORA work if no new money can be created?

\n

DORA operates on a \”zero-sum\” basis, meaning that Parliament cannot generate additional cash. Instead, it can only reallocate existing funds. If a new rand appears on one provincial spreadsheet, it must be counter-balanced by a rand deleted somewhere else. The total size of the financial \”pie\” remains the same; only the slices move. This often leads to intense debates and lobbying among provinces and departments over their share of the national budget for essential services like rural ambulances, school nutrition, and provincial road maintenance.

\n”,”answer”: “”},{“question”: “

Who are the key players involved in the DORA approval process?

\n

While the 400-seat National Assembly may have dispersed, the 90-member National Council of Provinces (NCOP) is central to DORA’s approval. Specifically, nine delegates, one from each province, gather virtually for the Select Committee on Appropriations to debate and decide on the allocations. The Treasury plays a significant role in identifying fresh budgetary holes that necessitate these reallocations. Although the NCOP has the constitutional power to accept, reject, or tweak the Bill, rejection is rare due to the potential freezing of billions in funds. The Finance Minister is also a key figure, especially if emergency measures are needed due to missed deadlines.

\n”,”answer”: “”},{“question”: “

What happens if the DORA Bill misses its deadline?

\n

If the delegates miss the statutory printing deadline, typically around December 20th, the Finance Minister must invoke an emergency procurement clause. While lawful, this is considered politically \”radioactive\” and undesirable. The urgency of meeting the deadline means that every decimal point of allocation is fiercely debated, as missing it could sideline Parliament and force the Treasury to act unilaterally, potentially leading to political fallout. Therefore, compromise often arrives in the final minutes to ensure the Bill is passed on time.

\n”,”answer”: “”},{“question”: “

What other parliamentary activities are linked to DORA in December?

\n

While the NCOP is finalizing DORA, the National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Appropriations also has crucial tasks. They must adopt three reports: the 2025 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) review and two Adjustment Appropriation Bills. These sessions, typically held around December 19th, ratify Treasury’s November numbers and send them to the Auditor-General. Opposition parties often use this opportunity to lodge minority opinions, which become part of the parliamentary archive and can even be cited by external bodies like Moody’s. These reports effectively close the formal ledger for the year but also lay the groundwork for next year’s financial battles.

\n”,”answer”: “”}]