Langa’s Special Quarters hostel, a dark symbol of apartheid and urban decay, was finally torn down. This sad place, once a “bachelor barracks,” became a dangerous, crime-filled building over 50 years. But in just one day, this nightmare structure crumbled into a harmless hill of dust and grit. Now, new dreams for mixed-income homes and a theater can sprout from its ashes. The fear that once lived there has blown away with the wind.

What was the fate of Langa’s Special Quarters hostel?

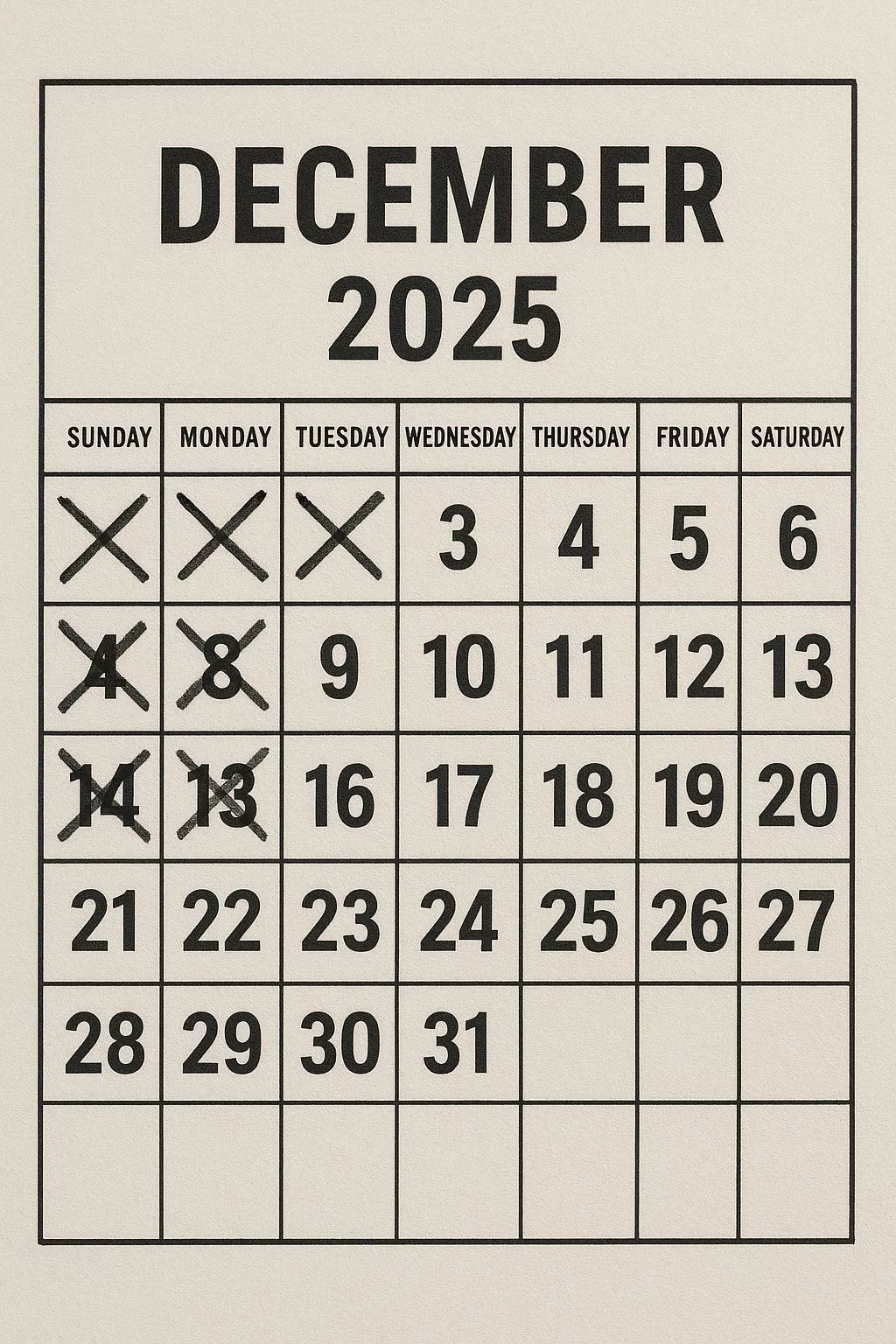

Langa’s Special Quarters hostel, a symbol of apartheid’s neglect and subsequent urban decay, was demolished in one day. Originally a “bachelor barracks” built in 1976, it became a crime-ridden structure in legal limbo before its demolition in December, transforming into a hill of grit.

Dawn of Dust and Diesel

Langa woke up tasting diesel. By first light, Washington Street already throbged with idling trucks and spectators hugging takeaway coffee. A lone yellow excavator inched forward, hydraulic arm raised like a boxer studying a battered opponent. The opponent was Special Quarters: four weather-punched storeys that had loomed over the township since 1976. Each time the bucket slammed in, cement coughed, cheers jumped, and another layer of history collapsed inward. No one needed a programme; every neighbour knew the script – this was the final scene of a horror story written in violence, neglect and court injunctions.

Children balanced on boundary walls, counting swings: “…eight, nine, ten!” A gogo clutched her Bible, whispering that the cracks resembled Moses’ broken tablets. Vendors threaded through the crowd selling fried dough and conspiracy theories about hidden treasure in the basement. None of it slowed the machine. By late afternoon the hostel had shrunk to a neat hill of pink grit and twisted rods, as harmless as a sandcastle awaiting the tide. The smell of wet cement lingered, but fear – fear was already blowing away with the wind.

Concrete Dreams Gone Sour

The block had risen in the same year that Soweto’s students took to the streets. Apartheid planners called it a “bachelor barracks”: 312 single cells, communal taps, latrines at both ends, a bell that tolled curfew at 22:00. Migrant men from the Ciskei and Transkei poured in, their pay packets seeding Cape Town’s white economy. Weekend courtyards pulsed with marabi keys, home-brew fermenting in enamel baths, and church harmonies that drifted across the railway line. Family day – last Saturday of each month – turned corridors into colourful outdoor lounges where women rewove torn bonds and kids tasted city life for twenty-four precious hours.

Freedom in 1986 dissolved the influx controls and the hostel’s fragile formula. Husbands fetched wives, fathers brought children; 312 rooms became 600, then 800. Municipal budgets dried under sanctions; lifts died, the borehole pump vanished, walls were sledge-hammered into double cubicles. After 1994 the new council tried to regularise occupancy, but paperwork was a maze – original tenants dead, rooms sub-let, title claims tangled. Courts blocked evictions; renovation funds evaporated. The building stalled in legal limbo while mushrooms sprouted from buckled parquet and roofs became a scrap-metal bazaar.

Violence wrote the next chapters. Gangs carved turfs, pimps booked ground-floor cubbyholes, tik addicts turned top storeys into a copper-burning cinema. Two street-patrollers were flung from the roof in 2007; after that, even paramedics radioed “no-go.” By 2003 only old Mr. Mzimeli remained legally on the ledger; a chunk of staircase in his lap persuaded officials to move him to a Gugulethu care home. From then on the structure breathed only through crime stats: 312 emergency calls in twelve years, 87 for GBH, 43 for “gravity incidents,” a police stamp that read Priority 1 Crime Generator.

When Ruins Sang

Even nightmares hum. After 2010, European graffiti crews bribed local teenagers with paint and beer, hunting “authentic” walls. They left Walter Sisulu in lime, Brenda Fassie in canary, a hooded kid releasing a pigeon that morphed into cassette ribbon. Architecture students followed, calling the shell “Africa’s High Line.” UCT graduate Anele Gwangwa wrote of the central air-shaft acting as an “urban drum,” its acoustics once boosting marabi, later kwaito basslines, making dereliction itself an instrument. While detectives joked about rubber-stamping “unknown male, stairwell,” artists Instagrammed sunlit shots of shattered chandeliers, proof that culture can colonise collapse.

Salvation, when it came, wore court robes and price tags. In 2018 inspectors labelled the block “unfit for rats,” placing it on the city’s Top 30 Dead Buildings list. An August 2019 expropriation ruling compensated only verifiable original tenants – eleven grandfathers, two widows – at 1998 valuations, enough for backyard shacks, little else. Demolition tender started at R4.2 million, ballooned to R6.8 million once asbestos was discovered. Treasury’s urban grant, a re-routed cycling-lane fund, and a hush-million from an adjacent developer finally closed the gap. Activists cried privatisation; officials warned of another Marikana if the place caught fire. Paperwork signed, the city bit the bullet.

Site prep felt like ritual cleansing. A leather-clad snake man pulled twenty-eight spitting cobras and one pregnant python from the sump, freeing them in N-2 wetlands. Moon-suited specialists peeled asbestos sheets, double-bagging for hazardous landfill. Then artists returned, diamond-sawing 4 m² portrait slabs. Sisulu’s gaze now greets visitors at the District-Six museum annexe; Brenda Fassie waits for 2027 inside the future Museum of Contemporary Art Africa at the Waterfront. Memory, like asbestos, needs careful handling.

Last Light on Washington Street

10 December played like New Year’s Eve. Sheep-head pots bubbled, a flat-bed truck pumped gqom, Methodist elders pressed hymnbooks to chests. At 9:00 sharp Alderman JP Smith crowned himself with a flag-painted helmet and pronounced the nightmare dead. A priest splashed holy water; a sangoma sent impepho spiralling skyward. The Cat 336 took the first bite beside the fading “Welcome Home” sign. By noon the facade hung like opera scenery: cables dangled like violin strings, a single ballet shoe and rusted Okapi knife clinging to rubble ribs. Spectators pointed – “Room 217, that’s where whoonga kings ruled”; “Head found here, body never” – half thriller, half home movie.

Thandeka Mbola, 68, fried vetkoek yards from the fence. She can still trace TM + DM carved on a third-floor brick: her and her late husband, 1981 newlyweds. She will build those initials into a garden bench so visitors ask and she can answer, “Love lived even here.” When the final slab collapsed, voices rose in “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” LED phones swarmed like fireflies, and for once no one flinched at shadows. Streetlights flickered on, fed by a cable the crews had re-routed; children zig-zagged through white cones without glancing back.

Midnight left only silence and security tape. Tomorrow topsoil will carpet the debris, shipping-container play structures will arrive painted in rescued mural colours. By March 2025 the City will invite bids for mixed-income flats, a 500-seat theatre cut into the old ground slab, a pedestrian spine linking Langa station to the new BRT terminus. Budget storms may yet shred those blueprints, but tonight residents walk home past Brenda blaring “

[{“question”: “What was Langa’s Special Quarters hostel?”, “answer”: “Langa’s Special Quarters hostel was originally built in 1976 as a \”bachelor barracks\” during the apartheid era to house migrant men. It contained 312 single cells with communal taps and latrines. Over its 50-year history, it transformed from a functional hostel into a dangerous, crime-ridden building, eventually becoming a symbol of urban decay.”}, {“question”: “When was the hostel demolished and what was the outcome?”, “answer”: “The hostel was demolished in one day, on December 10th. The structure, which had been a \”nightmare\” of crime and neglect, crumbled into a \”harmless hill of dust and grit.\” The demolition was a highly anticipated event, with residents gathering to witness the end of an era.”}, {“question”: “What were the conditions like in the hostel after apartheid ended?”, “answer”: “After the end of apartheid and the dissolution of influx controls in 1986, the hostel’s original structure and formula collapsed. Families moved in, leading to overcrowding (312 rooms became 600, then 800). Municipal budgets dried up, infrastructure failed, and the building fell into disrepair. It became a hub for gangs, crime, and drug activity, with incidents of violence making it a \”no-go\” area even for paramedics.”}, {“question”: “What attempts were made to address the hostel’s issues before demolition?”, “answer”: “Post-1994, the new council tried to regularize occupancy, but legal and administrative complexities (dead tenants, sub-lets, tangled claims) created a legal limbo. Renovation funds evaporated, and the building was eventually labeled \”unfit for rats\” in 2018, placing it on the city’s Top 30 Dead Buildings list. An expropriation ruling in August 2019 compensated some original tenants, and after overcoming financial hurdles and asbestos removal, the demolition tender was finalized.”}, {“question”: “Were there any cultural or artistic activities associated with the dilapidated hostel?”, “answer”: “Yes, even in its state of decay, the hostel attracted attention from artists and architects. After 2010, European graffiti crews created murals of figures like Walter Sisulu and Brenda Fassie. Architecture students, including UCT graduate Anele Gwangwa, wrote about its unique acoustics, calling the central air-shaft an \”urban drum.\” Some of these art pieces were salvaged before demolition, with portrait slabs now displayed in museums.”}, {“question”: “What are the future plans for the site of the former hostel?”, “answer”: “The site is planned for redevelopment with new dreams for mixed-income homes and a 500-seat theater cut into the old ground slab. There will also be a pedestrian spine linking Langa station to a new BRT terminus. Shipping-container play structures painted with rescued mural colors are also planned, with bids for the new developments expected by March 2025.”}]