A huge storm hit Kloof Road, making the mountain crumble! This road, built over 120 years, couldn’t handle the rain because of old cracks, tree roots, and acid rain. A big chunk of the mountain slid down, blocking the road and cutting off important internet cables. Now, fixing it is a tricky job, mixing old building ways with new tech to make the road safe again.

What caused the Kloof Road collapse in September 2023?

The Kloof Road collapse on September 8, 2023, was caused by an unprecedented storm delivering 76 mm of rain, which, combined with pre-existing cracks from drought, eucalyptus root damage, and acid rain, led to a landslide of 400 tonnes of material, disrupting vital infrastructure and transportation.

1. The Night the Mountain Let Go

At 03:42 on 8 September 2023, the wind gauge on Table Mountain’s upper cable station whipped round to 156 km/h, a figure no-one in Cape Town’s 210 years of weather-keeping had ever written down. A cut-off low – category nine – had parked itself 30 km south-south-west of Cape Point and was flinging a solid sheet of water at the city. Between 02:00 and 04:00, 76 mm of rain landed on the thin sandstone bench that carries Kloof Road. The 1890s stone walls – laid by Italian prisoners of war and pre-cracked by the 2017 drought – filled like ornamental ponds. Then the western flank of the Queen’s Cutting silently peeled away for 42 m. A 400-tonne cocktail of quartzitic sand, gum-tree roots and Victorian brick shot downhill at 9 m/s. When the debris stopped 120 m below, it had amputated the uphill lane, 35 m of century-old culvert, two fibre cables that carry 18 % of the country’s overseas data, and the only direct link between the City Bowl and Camps Bay. detours: 9 km over Kloof Nek or the hair-pin ballet of Victoria Road.

2. Why the City’s Pulse Beat Through This Three-Kilometre Shelf

Kloof Road began life in 1894 as a maintenance track for the Woodstock Reservoir; by the millennium it had become the Atlantic Seaboard’s jugular. Roughly 18 000 vehicles – dawn taxis, dusk ride-hails, seafood reefers, refuse rigs, 4×4 school-runners, e-bike food riders – squeeze along the 3,2 km between Kloof Nek circle and Camps Bay High every day. Its 1:8,5 gradient and the famous CamelBack hairpin slice eleven minutes off the peak-hour crawl. More importantly, the lowest 1,1 km is the sole driveway for 2 400 cliff-hanging mansions inside Table Mountain National Park, a World Heritage site whose fynbos torches itself every 12-15 years. When the road disappeared, the Risk Centre fed a 45 km/h north-westerly and a January fire day into a Monte-Carlo model: evacuation time for Clifton and Camps Bay ballooned from 72 minutes to 178 minutes – past the 120-minute survival limit of the oldest beachfront flats, built before fire escapes were imagined.

3. The Stack of Brittle Plates Nobody Noticed

Kloof Road does not sit on Table Mountain; it is stapled to its mid-slope scarp. The 520-million-year-old Peninsula Formation quartzites dip 25° south-east, looking reassuringly solid yet behaving like a pile of china plates. Where Victorian navvies sliced the Queen’s Cutting they uncovered a 14 m wedge of iron-stained, shattered rock. For 129 years, invasive eucalyptus roots levered the joints apart, summer heat-shock cycled daily ranges beyond 22 °C, and acid rain quietly dissolved the iron cement. The result: coarse gravel held together by friction and hope. The September storm supplied the final 4 % of pore-water pressure; the friction angle dropped below 18° and the mountain shrugged.

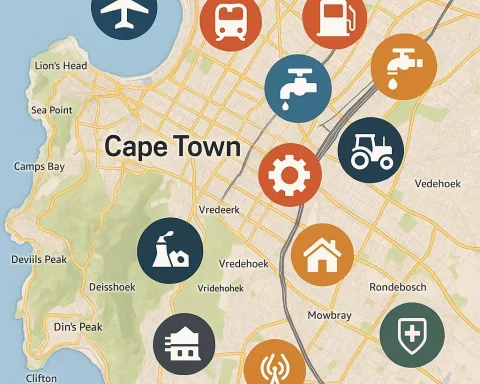

4. The Utilities That Went Over the Edge With the Asphalt

Before a single tyre can return, the City must rebuild the invisible city that lived in the collapsed shoulder. A 300 mm mild-steel water main that delivers 35 % of Camps Bay’s drinking supply burst, back-siphoning the 2-megalitre local reservoir dry in 42 minutes and forcing an instant Level-6 restriction. A 250 mm asbestos-cement sewer rising-main snapped, flushing 65 L/s of raw effluent down the kloof for 36 hours and pushing Clifton 4th beach past Blue Flag E-coli limits. A 22 kV bundled conductor on 1950s lattice poles sheared at pole 4K17, punching a 3 000-volt earth fault that blacked out 4 200 residents for two nights. Four 96-core fibre bundles – two City MetroConnect, two private back-hauls to Equinix CT1 – were severed, shaving 180 Gbit/s off South Africa’s international bandwidth and forcing Amazon Web Services to swing traffic to the JB3 cable at Mtunzini. Finally, a 1,2 m × 1,2 m brick culvert laid in 1908 – already throttled to a 1-in-2-year capacity by silt – lost 180 m. Winter runoff now free-falls over the scar, gnawing 30 mm deeper into the uphill lane every storm.

5. The Permit Maze Inside a World Heritage Site

Because the alignment lies inside Table Mountain National Park, reconstruction must run four statutory gauntlets simultaneously. A NEMA section 24G rectification – granted after 18 months and R2,3 million of specialist studies – kicked things off. Heritage Western Cape demanded a section 34 permit: the Queen’s Cutting is older than 60 years, so every masonry block had to be laser-scanned and RFID-tagged before touch. SPLUMA required a municipal board of inquiry because the temporary construction platform intrudes 4 m into the 1:20 flood-line of Camps Bay Stream. Lastly, a National Water Act licence controls dewatering of two perennial seeps that feed the last breeding population of the endangered Cape sand frog; the March 2025 permit insists a residual trickle of 0,8 L/s – about a garden hose – must run for the entire 11-month build.

6. Stitching a Mountain Back Together – Victorian Stone Meets Space-Age Mesh

The dream team – SMEC, Cullinan & Associates, and conservation engineer Dr. Louisa Brink – opted for a hybrid “stitch-and-sling” fix. First, a BROKK 400D robot scalps 1 200 m³ of loose sandstone while humans keep a 20 m buffer. Over the fresh face they fling 8 000 m² of 4 mm TECCO G65 mesh, stapled with 3 m self-draining stainless spikes rated at 150 kN/m – enough to park a loaded city bus on the slope. The collapsed 42 m of wall will rise again using the original 1894 sandstone, each block cleaned, catalogued and re-bedded on a 1 m-deep concrete grade-beam tied into bedrock with 32 mm threaded bar. Lime-pozzolan mortar (zero cement) keeps heritage purists happy and lets future engineers re-mine the stones if the mountain shifts. To slim the load, the new carriageway is a 9 m steel–concrete composite deck on 900 mm micropiles, shedding 35 % of dead weight and freeing a 2 m bio-corridor upslope for chacma baboon passage – an explicit TMNP condition. A 1,5 m French trench of geotextile and silcrete will intercept seepage, feeding twin 250 mm HDPE drains that daylight below the 2023 failure plane, ensuring the critical 4 % water rise never repeats. Eighteen wireless tilt-meters, five spider crack-meters and a 3 cm-resolution ICEYE SAR satellite feed will watch the slope; 0,2 mm/day of cumulative movement and the road closes automatically.

7. Building a Site That Has No Road In

Every nut, bolt and bag of cement must descend from the sky or be winched up the cliff. The only flat ground is an old quarry at the kloof foot, now a restoration site for the Red-List Erica verticillata. After six months of appeals, the City secured a 0,8 ha temporary lease on draconian terms: zero diesel plant inside the quarry – only battery-electric or Euro Stage-V kit with idle-stop; helicopter lifts restricted to dawn and dusk so thermal-riding Verreaux’s eagles (nesting 600 m east) can hunt in peace; 1 200 invasive gums to be felled, chipped and air-slung to a biomass boiler 34 km away in Atlantis, offsetting 1 100 t of CO₂ – roughly the embodied carbon of the new deck. Workers commute in a 42-seat battery-electric bus that trickle-charges overnight at Green Point depot; private cars are banned.

8. Who Foots the R298 Million Bill – and When Will It End?

The price tag, expressed in March 2025 rands, splits four ways: geotechnical stabilisation R132 m, road deck R71 m, utilities R48 m, compliance R22 m, helicopter logistics R25 m. Funding is a three-legged pot: R200 m from the City’s self-insurance fund (held up for six months while actuaries argued whether a storm is an “event” or “gradual geological decay”), R78 m re-allocated from the stalled Winelands bus-rapid-transit grant, and R20 m prepaid by Telkom, Vodacom, Amazon Web Services and the Camps Bay Ratepayers’ Association for five years of way-leave in the new embankment. The chronogram now reads: tender award January–February 2026, site hand-over March, anchors and mesh April–June, deck launch July–September, final surfacing October. If the frog continues to breed, the eagles keep hunting and the mountain stays put, the first commuter should drive the new CamelBack hairpin on 1 November 2026 – exactly 37 months after the mountain shrugged.

What caused the Kloof Road collapse?

The Kloof Road collapse on September 8, 2023, was primarily triggered by an unprecedented storm that delivered 76 mm of rain in just two hours. This heavy rainfall exacerbated existing vulnerabilities, including pre-cracked stone walls from a 2017 drought, damage from invasive eucalyptus tree roots, and the corrosive effects of acid rain. These factors collectively led to a 400-tonne landslide, severing vital infrastructure.

How old was the engineering that failed?

The initial construction of Kloof Road dates back to 1894, meaning the mountain engineering that failed was over 120 years old. The stone walls were laid by Italian prisoners of war, and while robust for their time, they were not designed to withstand the combination of modern stresses and extreme weather experienced in 2023.

What critical infrastructure was affected by the collapse?

The collapse had significant impacts beyond just the road itself. It severed two fibre optic cables responsible for carrying 18% of South Africa’s overseas data, disrupted a 300 mm water main supplying 35% of Camps Bay’s drinking water, broke a 250 mm sewer rising-main, and damaged a 22 kV power line, causing blackouts for 4,200 residents. A 1908 brick culvert was also destroyed.

Why is Kloof Road so important to Cape Town?

Kloof Road is critical as it serves as the main artery for approximately 18,000 vehicles daily between the City Bowl and Camps Bay. It’s also the sole direct access for 2,400 cliff-side residences within Table Mountain National Park, a World Heritage site. Its closure significantly increased evacuation times for coastal communities in case of emergencies like wildfires.

What is involved in repairing Kloof Road given its location?

Repairing Kloof Road is a complex undertaking due to its location within Table Mountain National Park, a World Heritage site. This requires navigating four simultaneous statutory gauntlets: NEMA section 24G rectification, a Heritage Western Cape section 34 permit for the 1894 walls, a SPLUMA inquiry for temporary construction, and a National Water Act license to protect endangered Cape sand frog habitats. The repair also involves a hybrid “stitch-and-sling” method using both Victorian stone and modern mesh technology.

When is Kloof Road expected to reopen and what is the cost?

Kloof Road is projected to reopen on November 1, 2026, approximately 37 months after the collapse. The total estimated cost for the repairs is R298 million (in March 2025 rands). This funding comes from a combination of the City’s self-insurance fund, re-allocated grants, and pre-payments from major utility and community organizations.