South Africa’s system for taking guns from abusers is broken. Court orders to grab weapons often go missing, like a ghost’s footprints. Different government offices don’t talk to each other, so abusers with protection orders can still get gun licenses. Even security guards can keep their work guns at home, turning normal weekends into danger zones. This broken system lets dangerous people keep their guns, putting many lives at risk.

How does South Africa allow abusers to keep their firearms despite protection orders?

South Africa’s system has several critical flaws allowing abusers to retain firearms: a “phantom trail” where court orders to confiscate guns are not consistently followed or documented, parallel and uncommunicative government software systems that fail to flag protection orders during license applications, and a lack of enforcement regarding service weapons used by security personnel. These systemic issues create significant loopholes, endangering victims of intimate partner violence.

The 18 Minutes That Changed Everything

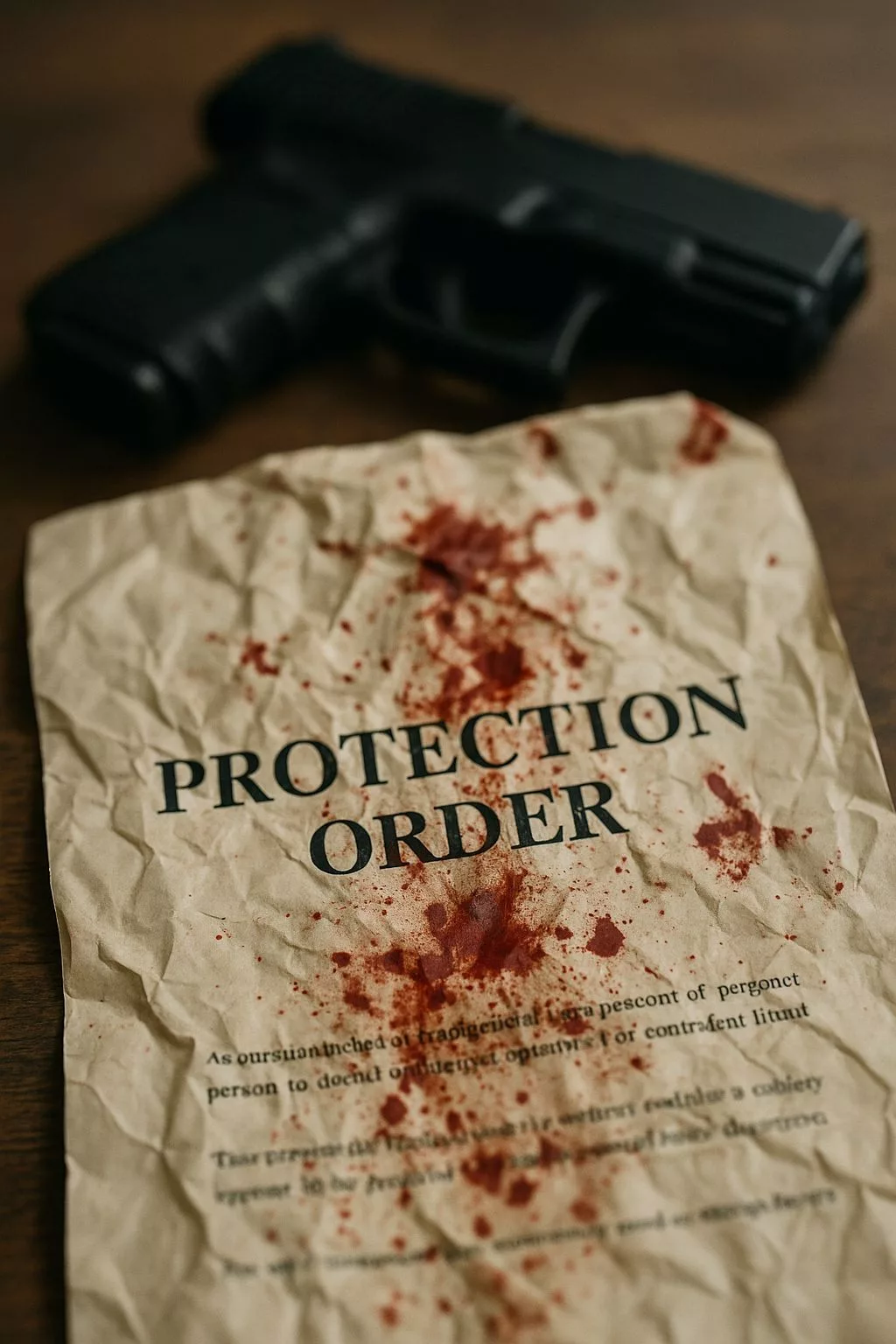

Just after half-past two on a humid September Sunday, Sasha Lee Shah updated her WhatsApp status to a single plea: “Help.”

Eighteen minutes later her ex-boyfriend, Kyle Inderlall, stood in her bedroom and emptied a company-owned 9 mm Z88 into her body.

The first slug tore through her shoulder while she frantically dialled 10111; the last shattered the phone still transmitting a three-minute-44-second call that nobody answered.

When Berea police reached the scene twenty-three minutes later, the handset was warm, the call still open.

A protection order, granted barely four weeks earlier, sat curled on the passenger seat like a discarded sweet wrapper.

Those eighteen minutes now headline a 112-page study, “Armed and Intimate,” unveiled this week by the Remove the Trigger coalition at Cape Town’s Saartjie Baartman Centre.

Researchers logged 431 intimate-partner gun killings between 2017 and 2022.

More than one in three weapons was fully licensed; another eleven percent were service pistols issued to security staff, police or cash-in-transit guards.

The report argues that the celebrated Firearms Control Act of 2000 works fine inside the state armoury and leaks like a colander once the gun walks through a private front door.

Paper That Disappears and Laws That Lie Dormant

Gender-violence specialist Lisa Vetten calls the deadliest hole the “phantom trail.”

A court may order the station commander to confiscate every firearm a respondent owns, yet no uniform form rides shotgun with the sheriff.

“The docket turns right, the court order turns left, the pistol goes straight back to the night-stand,” Vetten told the Athlone audience.

Her team demanded 89 court files from five magisterial districts.

Clerks produced the protection order in seventy-two instances; detectives could show a return-of-service slip proving guns were removed in only two.

The remaining slips were AWOL – wedged under car-boot spare tyres, filed under “domestic–miscellaneous,” or simply never uploaded to the CAS system.

Without that slip the court cannot cite the police for contempt; without contempt the weapon stays within arm’s reach.

South African statute already bars anyone hit with a final protection order from holding a firearm licence.

Reality tells a different tale.

Home Affairs and the Central Firearm Registry run parallel software that “greet each other like strangers sharing a lift,” says an insider.

A protection order issued in Pietermaritzburg is invisible to the licensing desk in Pretoria unless the applicant herself couriers a copy for R117.

Even when the document lands, the system lacks a drop-down field marked “domestic-abuse flag”; staff must open fourteen screens to locate a scanned PDF.

Between 2017 and 2022 a grand total of ninety-two new licence applications were formally rejected because of intimate-partner violence – 0.03 percent of all submissions.

When the Paycheck Comes With a Holster

Kyle Inderlall was no rogue outlier.

Researchers matched the 431 killings against PSIRA’s register and found fifty-three active security guards among the killers.

Industry slang calls the practice “weekend carry”: book the pistol out on Friday, stash it at home until Monday.

One Durban firm hands each guard forty live rounds on a Friday “for personal protection” and asks only for leftovers on Monday morning.

Nobody logs how many bullets leave the barrel in between.

Henrietta du Preez, a former police constable, told the launch how her police-ex husband turned breakfast into a ballistics class.

“He wiped down his service pistol while the children ate cereal.

When he lost his temper he’d yank the slide and bounce a live round onto my plate.

Gun-oil odour still makes me vomit.”

She obtained a protection order in 2019; the station commander refused to touch the firearm, claiming it was state kit and confiscation would be “theft.”

Du Preez eventually fled the province; her ex patrols Upington streets with the same weapon today.

The economic toll is equally chilling.

Each femicide costs the state roughly R4.7 million – ambulance, autopsy, lost wages, funeral, trauma counselling, investigation.

Multiply by 431 gun-related intimate-partner killings and the bill tops R2 billion in five years, enough cash to open twenty-six new Thuthuzla Care Centres or hire fourteen hundred specialist domestic-violence officers.

The cheapest remedy – taking away the gun – costs almost nothing.

In 2021 the Western Cape Department of Community Safety trialled a single-page “firearm-removal checklist” for magistrates and trained cops to file a DA-7 form within twenty-four hours of a protection order.

Seventy-eight weapons were seized during the six-month pilot; the same period the previous year saw twelve.

Treasury refused a R3.8 million rollover; the initiative died.

Ghost Rounds, Ghost Laws, Real Bodies

Roughly one in five murder weapons was never recovered; dockets list “unknown 9 mm” or “possible R5.”

Many are grey-market firearms – licences not cancelled after death, or police rifles rented out for “weekend jobs.”

A Durban pawn-broker on hidden camera bragged he leases police R5s for R500 a night, no ID required.

Victims increasingly document threats on WhatsApp: 412 of 3,200 analysed messages contained direct firearm threats, sixty-four included a photo of the gun.

Only seventeen threads made it into evidence because the Electronic Communications and Transactions Act demands a 65-step chain-of-custody affidavit costing R2,800 within forty-eight hours.

Most survivors cannot pay; most stations lack the extraction software.

Remove the Trigger wants three quick fixes:

– a mandatory DA-11 “Firearm Surrender Form” that must land in court within forty-eight hours;

– an automatic domestic-violence flag that freezes any licence linked to the abuser’s ID the moment a final protection order is granted;

– an annual public audit by the Civilian Secretariat listing guns seized, disciplinary actions against non-compliant officers and licences denied because of intimate-partner abuse.

The ministry received the proposals in March 2023; officials have yet to respond.

While bureaucracy stalls, women adapt.

The Ballistic Feminists of Gugulethu meet each Saturday to learn field-stripping on decommissioned police pistols – turning metal into testimony.

In Mitchells Plain volunteers conduct “gun-free home” visits; 634 firearms have been swapped for R50 grocery vouchers, half of them linked, within weeks, to affidavits describing previous threats.

A Cape Town start-up is beta-testing an app that opens an eighteen-minute countdown the moment a user views her protection-order PDF.

Fail to punch in a safe code and your microphone streams the last two minutes of audio to a secure evidence locker.

The developers offered the platform free to the Justice Department; the file has gathered dust since January.

Back in Athlone the launch ended with 431 black T-shirts pegged along a corridor – each printed with a name, a date, a calibre.

Visitors clipped blank pages beside them, placeholders for return-of-service slips that never appeared.

By sunset eighty-seven pages flapped in the Cape Doctor wind.

One, already fading, read: Sasha Lee Shah, 18 September 2022, 9 mm – still missing.

How does South Africa allow abusers to keep their firearms despite protection orders?

South Africa’s system has several critical flaws allowing abusers to retain firearms: a “phantom trail” where court orders to confiscate guns are not consistently followed or documented, parallel and uncommunicative government software systems that fail to flag protection orders during license applications, and a lack of enforcement regarding service weapons used by security personnel. These systemic issues create significant loopholes, endangering victims of intimate partner violence.

What is the “phantom trail” and how does it contribute to the problem?

The “phantom trail” refers to the breakdown in the process of confiscating firearms after a court issues a protection order. Gender-violence specialist Lisa Vetten describes it as court dockets turning one way while court orders turn another, leading to firearms remaining with abusers. This happens because there’s no uniform form that accompanies the sheriff to ensure confiscation, and return-of-service slips proving guns were removed are often missing or improperly filed, making it impossible for courts to cite police for contempt and enforce the order.

How do government systems fail to prevent abusers from getting or keeping gun licenses?

Home Affairs and the Central Firearm Registry operate on parallel software systems that don’t communicate effectively. This means a protection order issued in one jurisdiction is often invisible to the licensing desk in another. Even if a physical copy of the protection order is provided, the system lacks a dedicated “domestic-abuse flag” field, requiring staff to navigate through multiple screens to locate scanned documents. This inefficiency results in a shockingly low number of license applications (0.03%) being rejected due to intimate-partner violence between 2017 and 2022.

What is “weekend carry” and why is it a significant risk?

“Weekend carry” is industry slang referring to security guards booking out their company-issued service pistols on Friday and taking them home until Monday. This practice turns normal weekends into danger zones, as these weapons can be used in domestic disputes. The report found that 11% of intimate-partner gun killings between 2017 and 2022 involved service pistols issued to security staff, police, or cash-in-transit guards, highlighting the severe risk posed by this unregulated practice.

What are the economic consequences of intimate partner gun violence in South Africa?

The economic toll of intimate partner gun violence is substantial. Each femicide costs the state approximately R4.7 million, covering expenses such as ambulance services, autopsies, lost wages, funerals, trauma counseling, and investigations. With 431 gun-related intimate-partner killings between 2017 and 2022, the total cost exceeds R2 billion over five years. This amount could otherwise fund 26 new Thuthuzla Care Centres or hire 1,400 specialist domestic-violence officers, demonstrating that the cheapest and most effective remedy – taking away the gun – is often overlooked.

What immediate solutions has the “Remove the Trigger” coalition proposed?

The “Remove the Trigger” coalition has proposed three quick fixes to address the systemic failures: 1) A mandatory DA-11 “Firearm Surrender Form” that must be submitted to the court within forty-eight hours of a protection order being granted. 2) An automatic domestic-violence flag that instantly freezes any firearm license linked to an abuser’s ID once a final protection order is issued. 3) An annual public audit by the Civilian Secretariat detailing guns seized, disciplinary actions against non-compliant officers, and licenses denied due to intimate-partner abuse. These proposals aim to introduce accountability and streamline the process of removing guns from abusers.