South Africa’s prisons are bursting at the seams, mainly because many people wait too long for their trials and alternatives to jail aren’t used enough. Laws like Section 49G and 62F were made to protect detainees from long waits and offer supervised bail, but slow courts and scarce resources make these rules hard to follow. Inside overcrowded cells, people lose hope as they wait months or years just for a chance to be heard. Some small community efforts bring help and light, but real change needs more than laws—it needs the justice system and society to care deeply and act quickly.

What causes overcrowding in South African prisons and how is it addressed?

Overcrowding in South African prisons is primarily caused by lengthy pre-trial detention and limited use of alternatives to incarceration. Laws like Section 49G and Section 62F aim to reduce this by enforcing timely judicial reviews and supervised bail, but challenges like court backlogs and resource shortages hinder effective implementation.

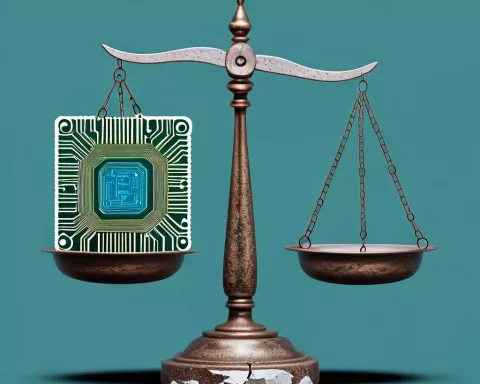

The Weight of Overcrowding in South African Prisons

South Africa’s correctional facilities have reached a critical point, with overcrowding dominating every debate in the justice sector. As officials and lawmakers examine the roots of this persistent crisis, the Portfolio Committee on Correctional Services recently dove into the heart of the issue, asking tough questions about the laws designed to prevent prisons from bursting at the seams. Their discussions, often charged with urgency and exasperation, centered on two pivotal legal mechanisms: Section 49G of the Correctional Services Act and Section 62F of the Criminal Procedures Act. Both sections were crafted to act as pressure valves, aiming to reduce the relentless influx of detainees and stem the tide of overpopulation.

A walk through one of the country’s bustling remand centers quickly reveals the human toll. Detainees dwell in a state of limbo, caught between the presumption of innocence and the reality of confinement. Section 49G was enacted to shield individuals from indefinite pre-trial imprisonment. This law clearly states that no remand detainee should be held for more than two years without a judicial review of their case. Heads of correctional facilities must submit these extended cases to court three months before the two-year threshold, allowing a judge to decide whether continued detention remains necessary. The process doesn’t end there—if the court determines detention should continue, a similar review must recur every year.

Despite these safeguards, the system frequently stumbles. During a 2024 committee briefing, officials revealed that, of the 12,283 cases referred to the courts under Section 49G in the 2022/23 financial year, judges approved only 1.25% for release. In some regions, such as the Eastern and Western Cape, not a single remand detainee benefited from the review process. This minuscule approval rate highlights a justice system weighed down by caution, administrative backlog, and public pressure to appear tough on crime. Each denied release adds another body to already strained facilities, compounding the crisis year after year.

Beyond the Letter of the Law: Practical Barriers and Lived Experiences

During the committee’s investigation, members shared personal accounts that painted a vivid picture of the crisis on the ground. One member recounted meeting a detainee in Cape Town who had waited thirty-two months—almost three years—before his trial even began. His story echoes that of countless others, all waiting for the slow gears of justice to recognize their plight. These narratives bring to life the gap between legislative ideals and the daily reality experienced by thousands of men and women behind bars.

Section 62F of the Criminal Procedures Act offers another tool, letting courts place awaiting-trial detainees under supervised bail rather than in crowded cells. In theory, this could ease overcrowding while ensuring accused persons remain accountable. Yet in practice, authorities struggle to monitor those released under supervision, especially in rural regions where resources and infrastructure are limited. Overstretched correctional staff find themselves unable to keep up with the demands of both supervising released individuals and managing those still incarcerated.

Chairperson Kgomotso Anthea Ramolobeng summed up the dilemma by highlighting the persistence of long-term incarceration. Roughly 40% of sentenced prisoners are serving fifteen years or more, with a significant portion facing life sentences. Unlike short-term offenders, these individuals rarely leave, which means their beds remain occupied for decades. With new detainees arriving constantly, the system never gets a break, and the available space shrinks even further. This entrenched reality means that, no matter how many new laws get passed, the problem of overcrowding cannot be solved by simply moving people through the system faster.

The Broader Context: Historical Legacies and International Parallels

The challenge facing South African prisons is not unprecedented. Debates about the purpose and function of incarceration stretch back centuries, from Enlightenment-era thinkers like Jeremy Bentham to modern critics such as Michel Foucault. Every correctional system, shaped by its own history and culture, must balance the goals of punishment, rehabilitation, and the preservation of human dignity. Nowhere does this balancing act carry more weight than in South Africa, a country still wrestling with the legacies of apartheid and striving to transform its justice system.

The roots of lengthy pre-trial detention run deep, tracing back to colonial laws that prioritized state control over individual rights. In the post-apartheid era, lawmakers aimed to correct these injustices, embedding new protections into statutes like the Correctional Services Act. Unfortunately, well-intentioned laws often prove inadequate when confronted by clogged courts, limited resources, and political reluctance to change. Defense attorneys commonly voice their frustration: “South Africa has progressive laws on the books, but in reality, my clients wait years for a fair hearing.”

Inside the prisons, the overcrowded conditions feed countless problems. Cells designed for twenty inmates sometimes house forty. This overcrowding erodes any sense of safety or dignity, fueling violence, illness, and hopelessness. Creative expressions, such as murals of birds or endless staircases, decorate the walls—a testament to the longing for freedom and the need for hope. Overworked staff struggle to provide even basic services, while rehabilitation and educational programs often fall by the wayside.

Searching for Solutions: Alternatives, Innovations, and the Road Ahead

Many reformers argue that the solution lies in turning away from custodial sentences for non-violent offenders. They propose alternatives such as community service, restorative justice circles, probation, and electronic monitoring. These ideas draw inspiration from indigenous justice traditions and more recent experiments in Europe and North America. However, each approach faces significant obstacles. Politicians often fear being labeled “soft on crime,” while logistical and financial constraints limit what can be implemented on the ground.

Some provinces have turned to innovative partnerships to ease the crisis. In Gauteng, for example, civil society organizations now join forces with correctional officials to offer legal aid and mediation. These grassroots efforts, though still small, show what a responsive and humane system might look like. Volunteers have shared stories of individuals released thanks to timely mediation or legal assistance, experiences that highlight the potential for positive change when communities get involved.

The international community closely watches South Africa’s efforts. Agencies like the United Nations note the country’s paradox: it boasts some of the continent’s most advanced legal frameworks for detention but continues to struggle with overcrowding and lengthy pre-trial detention. Similar patterns can be seen in countries like Brazil, India, and the United States, where legal reforms often fall short when measured against institutional inertia and public anxiety.

Inside the walls, inmates and staff continue to adapt. Prisoners create chess sets out of bread or organize study groups, seeking meaning amid the chaos. Correctional officers, faced with daily challenges, sometimes display remarkable creativity by organizing literacy classes or mediating disputes with limited resources. These acts of resilience and ingenuity offer hope and underscore the human capacity to endure and even thrive, despite systemic shortcomings.

By examining the workings of Section 49G and Section 62F, the Portfolio Committee shines a light on more than just legal failings. Their scrutiny exposes the complex intersection between law, bureaucracy, and lived experience. The challenge goes beyond drafting new statutes—it demands a renewed commitment to the values that fueled South Africa’s journey to democracy. As long as thousands remain trapped in a cycle of uncertainty and delay, the call for reform—and for compassion—will only grow louder.

What are the main causes of overcrowding in South African prisons?

Overcrowding in South African prisons is primarily caused by lengthy pre-trial detention periods and the limited use of alternatives to incarceration. Many detainees wait months or even years for their trials to begin, contributing significantly to the number of inmates held in remand centers. Additionally, systemic issues such as court backlogs, slow judicial processes, and scarce resources hinder the effective implementation of laws designed to reduce prison populations.

How do Section 49G and Section 62F help address prison overcrowding?

Section 49G of the Correctional Services Act mandates judicial reviews for detainees held on remand for more than two years, aiming to prevent indefinite pre-trial detention. Heads of correctional facilities must refer cases to the courts three months before the two-year mark, and courts must review continued detention annually if necessary.

Section 62F of the Criminal Procedures Act allows courts to grant supervised bail to awaiting-trial detainees instead of keeping them behind bars, providing an alternative to incarceration. Both sections are intended as legal tools to reduce overcrowding by ensuring timely case reviews and promoting alternatives to detention.

Why are these laws not effectively reducing overcrowding?

Despite the safeguards offered by Sections 49G and 62F, several practical barriers limit their effectiveness. Courts are burdened by backlogs and administrative delays, resulting in very few detainees being released through judicial review. For example, only about 1.25% of cases referred under Section 49G led to release in 2022/23, with some regions granting no releases at all.

Supervised bail under Section 62F faces challenges due to insufficient infrastructure and personnel to monitor released individuals, especially in rural areas. Additionally, political pressure to appear tough on crime and limited resources hinder the adoption of non-custodial measures.

What are the living conditions like inside overcrowded prisons?

Overcrowded prisons often house twice the intended number of inmates, with cells built for twenty people sometimes holding forty. This congestion severely impacts safety, sanitation, and mental health. It fuels violence, the spread of diseases, and feelings of hopelessness among prisoners.

Despite these harsh conditions, prisoners and staff show resilience. Inmates create art and organize study groups to maintain hope, while correctional officers sometimes run literacy classes and mediate disputes using limited resources.

What are some proposed solutions to reduce overcrowding in South Africa’s prisons?

Reformers advocate for expanding alternatives to custodial sentences for non-violent offenders, such as community service, probation, restorative justice, and electronic monitoring. These measures draw on both indigenous justice practices and international innovations.

Grassroots partnerships between civil society and correctional services have begun to offer legal aid and mediation, helping some detainees secure release. However, political reluctance, public fear of crime, and resource constraints remain obstacles to scaling these solutions nationwide.

How does South Africa’s prison overcrowding issue compare internationally?

South Africa’s struggle with overcrowding and lengthy pre-trial detention reflects a global challenge seen in countries like Brazil, India, and the United States. While South Africa has progressive legal frameworks to protect detainees’ rights, institutional inertia, court delays, and social pressures undermine these protections in practice.

This situation highlights the complex relationship between law, bureaucracy, and societal attitudes toward crime and punishment, underscoring the need for comprehensive reforms that go beyond legislation to include judicial efficiency, resource allocation, and community involvement.