South Africa is making a huge change to its fuel by 2027! All petrol and diesel must be super clean, with very little sulfur. This means big factories have to spend lots of money to upgrade their machines, and even the long pipes that carry fuel need a special scrub. Drivers will pay a little more for this cleaner fuel, but it will make cars run better and help the air. It’s a race against time to get everything ready, and the whole country is watching this big fuel makeover!

What is the “Cleaner Fuels Two” standard in South Africa?

The “Cleaner Fuels Two” standard mandates that by September 1, 2027, all petrol and diesel sold in South Africa must contain no more than 10 parts per million (ppm) of sulfur, significantly lowering previous limits. This regulation also caps benzene at 1%, aromatics below 35%, and requires a diesel cetane of 51 or higher, aligning South Africa’s fuel quality with European standards.

1. From Embargo to Regulation: Why 2027 Changes Everything

South Africa’s fuel industry is bracing for its biggest shake-up since Sasol built coal-to-liquid plants during the apartheid oil embargo. This time the trigger is not a shortage of crude but a legal deadline: after 1 September 2027 every litre of petrol or diesel sold anywhere in the country must contain no more than 10 parts per million of sulphur. The Department of Mineral Resources and Energy locked the so-called “Cleaner Fuels Two” standard into law in 2022 and, after two postponements, says the date is now non-negotiable.

The new spec sheet reads like a European sticker: 10 ppm sulphur, benzene capped at one per cent, aromatics below 35 per cent and diesel cetane at 51 or higher. While the chemistry looks dry on paper, it is already redrawing import maps, igniting a race for hydrogen and quietly deciding who will actually still manufacture fuel inside the Southern African Customs Union.

Domestic refinery capacity tells the story. Four years ago the country could theoretically process 704 000 barrels of crude each day; today only two plants remain on-stream. Engen’s Durban refinery never reopened after the July 2021 riots, BP-Shell’s Sapref has been cold since 2022 and PetroSA’s gas-to-liquids complex was mothballed in 2020. Roughly sixty per cent of South Africa’s 490 000 bbl/d liquid-fuel appetite is now satisfied by imports, with the diesel share closer to eighty per cent. Officials concede that if Durban’s Island View tank farm loses electricity for more than a day and a half, Gauteng’s fuel supply becomes a single-point-of-failure statistic.

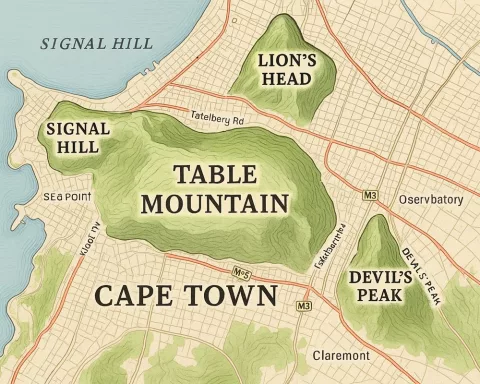

2. Inside the Only Two Plants Still Running

Astron Energy’s 100 000 bbl/d Cape Town site and Sasol’s 180 000 bbl/d Natref plant in Sasolburg are the only refineries left that can still crack crude. Both have committed to spend big or shut. Astron has already sunk USD 110 million into front-end designs for a 35 000 bbl/d continuous catalytic reformer and a 22 000 bbl/d naphtha hydrotreater, the kit needed to squeeze benzene below one per cent. A second wave of USD 218 million adds a 40 000 bbl/d diesel hydrotreater and an 8-tonne-per-hour green-hydrogen compressor; mechanical completion is pencilled for the last quarter of 2026, giving a slim nine-month margin before the law kicks in.

Natref is choosing a different chemistry set. Instead of a classic diesel hydrotreater it will retrofit its 1993 mild hydrocracker with a high-pressure sulphuric-acid alkylation unit and a 15 MW electrolyser able to pump 2 400 normal cubic metres of hydrogen every hour, the largest such unit in Africa outside Egypt. The electrolyser will run on renewable power wheeled through Eskom from a 200 MW solar park that Sasol signed in Sasolburg. Both sites have locked in Johnson Matthey’s newest SynSat catalysts, able to push sulphur from 500 ppm to below five ppm in a single pass, a performance engineers say was impossible with South Africa’s naphthenic crudes only five years ago.

Durban’s old Sapref footprint could yet rise again, but only if time and money bend. A leaked government paper floats a 250 000 bbl/d “Durban Clean Fuels Complex” with a condensate splitter and a 1.2 million tonne aromatics train, a USD 3.5 billion dream being peddled to Saudi Aramco, Oman’s OQ and a Japanese group led by JGC. Environmental auditors warn that 1.8 million cubic metres of oil-soaked soil must be bioremediated first, a 30-month choreography even with forced aeration. First oil could not flow before 2029 unless the minister grants a conditional licence, something he has so far refused to entertain.

3. Pipelines, Ports and the Invisible Clean-Up

Even if local plants hit the 10 ppm mark, South Africa will still need to import roughly 180 000 bbl/d of clean product by 2028. The catch is the 1 200 km multi-product pipeline network that links Durban to Gauteng was laid in 1965 for 500 ppm fuel. Sulphur molecules cling to pipe walls and later bleed into fresh batches, a ghost contamination that can push readings above 15 ppm at the inland end. Transnet has therefore embarked on a chemical scrub never tried at this scale: every kilometre of 16–24 inch pipe will be scoured with biodegradable biosurfactants, then coated with an epoxy-phenolic lining normally reserved for aviation hydrants.

The exercise demands six rotating 21-day shutdowns and 1.6 billion litres of temporary storage hired in Johannesburg and Kroonstad. The bill comes to R4.3 billion and will be clawed back through an inland-tariff surcharge of 8.7 cents per litre starting January 2026. While motorists will feel the extra cents, the alternative is a permanent contamination loop that would make a mockery of the new sulphur cap.

Hydrogen is the hidden ingredient in every ultra-low-sulphur recipe. Diesel hydrotreaters guzzle 1.1–1.3 normal cubic metres of hydrogen for every cubic metre of 500 ppm feedstock. South Africa’s lone merchant plant, Air Products’ 30 000 Nm³/h unit in Umbogintwini, already runs at 92 per cent capacity. Three new sources are sprinting to plug the gap: Sasolburg’s 2 400 Nm³/h green stream in 2026, Richards Bay’s “South Green” 600 MW solar-to-hydrogen venture targeting 5 000 Nm³/h by 2027, and a 20 000 Nm³/h blue-hydrogen plant linked to PetroSA’s revived GTL scheme that will import Mozambican gas and store 1.1 million tonnes of CO₂ a year in the depleted Oribi field off Mossel Bay, the country’s first carbon-sequestration project.

4. Show Me the Money: Who Pays and Who Profits

Clean-fuel hardware is classed as “strategic infrastructure”, which lets refiners recover costs through regulated levies that sit on top of the basic fuel price. National Energy Regulator of South Africa has already stamped a 14.8 c/l “CF2 regulatory levy” that will show up on every petrol and diesel receipt from April 2026; a further 7.2 c/l for the pipeline scrub follows in 2027. Together the 22 c/l surcharge adds R110 to a 50-litre fill-up, enough to shove the petrol price above R25 per litre if Brent lingers at USD 75 per barrel. Treasury softened the blow by scrapping the old 10 c/l demand-side levy, but economists warn taxi fares could still climb six per cent unless provinces expand fuel-voucher subsidies.

Vehicle technology is already waiting for the fuel to catch up. Forty-six per cent of South Africa’s passenger engines are Euro 5/6 ready, yet assemblers deliberately “derate” injection pressures to protect pumps from 50 ppm sulphur. Once 10 ppm is ubiquitous, OEMs can unlock full Euro-6 calibrations, cutting urban NOx by 28 per cent even if the car mix stays the same. Truck fleets stand to save R18 000 per articulated vehicle each year because cleaner fuel lets oil-drain intervals stretch from 40 000 km to 65 000 km.

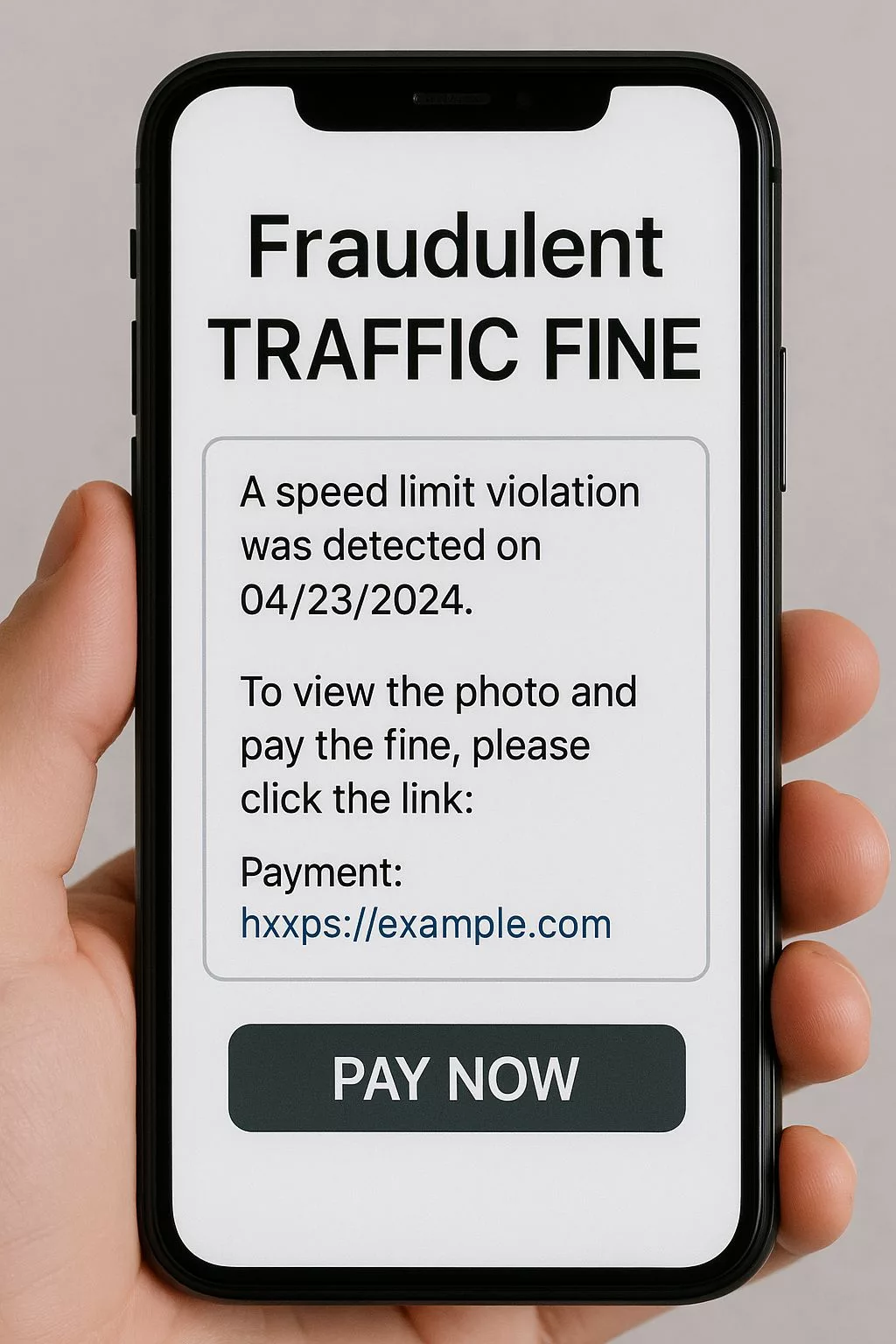

None of this will matter if the informal diesel trade keeps dodging the rules. Bakkie traders currently move 160 million litres of 500 ppm diesel a year to mines, farms and construction sites. From 2027 any distributor who knowingly off-loads non-compliant fuel outside the licensed network faces five years in jail. Revenue inspectors are already dosing diesel with micro-dotted dye and scanning sulphur with handheld X-ray guns in 30 seconds, a trick borrowed from Ghanaian anti-smuggler units. Mining houses are signing direct-lift agreements with Sasol and Astron, willing to pay a 25 c/l premium for traceable 10 ppm batches rather than risk criminal liability.

Neighbours feel the ripple. Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho and Eswatini buy 70 per cent of their fuel through South African pipelines or Durban berths. None has legislated 10 ppm, yet they will be dragged along because coastal blending happens in South African tanks. Botswana’s state oil firm has told customers that 50 ppm diesel will simply disappear after February 2027; Maputo’s Matola terminal is scrambling to triple storage to 900 000 m³ in case SACU members decide to reroute their business.

Skills shortages, labour clauses and carbon accounting add extra layers of drama. The country needs 2 400 specialised welders for chrome-rich reactor alloys but only has 900 on its red-seal books. A training blitz is under way, yet unions have secured EIA clauses that force 60 per cent local labour and ban retrenchments during commissioning. Ironically, the sulphur cleanup will also shave 350 kilotonnes of CO₂-equivalent each year simply because engines burn cleaner, giving South Africa a 5 per cent head-start toward its 2030 climate pledge without touching electricity demand.

The calendar is now measured in months. If Astron’s diesel hydrotreater is not mechanically complete by October 2026, inland tanks will miss the 90-day clean-batch cushion Transnet needs. If Sasol’s electrolyser is not 95 per cent available by May 2026, Natref will have to buy merchant hydrogen and pump refining margins up nine per cent, a cost that goes straight onto the garage price board. Officials whisper that 2026 is “the year nobody can blink,” and still keep a temporary 5 ppm waiver in their back pocket should both refineries stumble. Such a safety valve would leave the country cleaner than today, yet shatter its hard-won Euro-5 credibility with every global carmaker watching from the sidelines.

[{“question”: “

What is the ‘Cleaner Fuels Two’ standard in South Africa and when does it take effect?

\n

The \”Cleaner Fuels Two\” standard, mandated by the South African Department of Mineral Resources and Energy in 2022, requires that by September 1, 2027, all petrol and diesel sold in South Africa must contain no more than 10 parts per million (ppm) of sulfur. This is a significant reduction from previous limits. Additionally, the standard caps benzene at 1%, aromatics below 35%, and requires a diesel cetane number of 51 or higher, aligning South Africa’s fuel quality with European standards. This legal deadline is now considered non-negotiable after two postponements.

\n\n

Why is South Africa implementing these new fuel standards?

\n

South Africa is implementing these new fuel standards primarily to improve air quality, enhance vehicle performance, and align with international environmental and technological advancements. Cleaner fuel with lower sulfur content reduces harmful emissions like nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter, which are detrimental to public health and the environment. It also allows modern vehicle engines (many of which are already Euro 5/6 ready) to operate at their optimal performance, leading to better fuel efficiency and longer component life for vehicles, especially for heavy-duty trucks.

\n\n

What are the major challenges for refineries in meeting the 2027 deadline?

\n

The major challenges for refineries include the substantial capital investment required for upgrading existing infrastructure and the tight timeline. Only two refineries, Astron Energy’s Cape Town site and Sasol’s Natref plant, remain operational and are undertaking significant upgrades. These upgrades involve installing new units like continuous catalytic reformers, naphtha hydrotreaters, and diesel hydrotreaters, as well as integrating green hydrogen production. The mechanical completion of these projects is scheduled perilously close to the September 2027 deadline, leaving very little margin for error or delays.

\n\n

How will the new fuel standards affect fuel prices for consumers?

\n

Consumers will experience an increase in fuel prices due to the \”Cleaner Fuels Two\” regulatory levy and the cost recovery for pipeline cleaning. A 14.8 c/l CF2 regulatory levy will be added from April 2026, followed by a 7.2 c/l surcharge for the pipeline scrub in 2027, totaling an additional 22 c/l. This means an extra R110 for a 50-liter fill-up. While the old 10 c/l demand-side levy has been scrapped to soften the blow, economists warn that taxi fares could still increase by about six percent without additional subsidies.

\n\n

What infrastructure changes are needed beyond the refineries?

\n

Beyond the refineries, significant changes are required for the country’s fuel distribution network. The 1,200 km multi-product pipeline network connecting Durban to Gauteng, originally laid for 500 ppm fuel, must undergo extensive cleaning to prevent ghost contamination. This involves a chemical scrub with biodegradable biosurfactants and coating the pipes with an epoxy-phenolic lining. This process requires multiple 21-day shutdowns and the hiring of 1.6 billion liters of temporary storage, costing R4.3 billion, which will be recovered through an inland-tariff surcharge.

\n\n

How will the new standards impact South Africa’s neighbours?

\n

South Africa’s neighbours, including Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho, and Eswatini, which purchase about 70 percent of their fuel through South African pipelines or Durban berths, will be directly impacted. Although none of these countries have legislated 10 ppm fuel, they will effectively be dragged along as coastal blending and supply will conform to the South African standard. For example, Botswana’s state oil firm has already informed customers that 50 ppm diesel will disappear after February 2027, and terminals like Maputo’s Matola are scrambling to increase storage capacity in anticipation of potential rerouting of business.