South Africa is facing a big problem with driver’s licences because an old, single machine broke down, stopping over 600,000 licences from being printed. This mess came from years of poor planning and delays, leaving many drivers stuck and worried about their legal right to drive. The government is trying new ideas, like making a new printing machine with help from another department, and giving drivers a grace period while they fix things. Despite the troubles, people keep hoping and working together to find solutions and get back on the road.

What is causing the driver’s licence crisis in South Africa?

The crisis is caused by procurement failures, reliance on a single outdated card printing machine, and resulting backlogs of over 600,000 unprinted licences. Government collaboration, innovation, and temporary grace periods aim to resolve delays affecting millions of South African drivers.

Historical Fault Lines: Procurement Woes and the Road to Crisis

Deep within the machinery of South African bureaucracy, a far-reaching challenge has emerged, emblematic of wider systemic fragility and the occasional flash of resilience. The saga of the driver’s licence card crisis finds its origins not in the present-day offices of the Department of Transport, but in a troubled legacy of mismanaged tenders. For years, irregularities in awarding government contracts have haunted major projects, feeding into an ecosystem marked by inefficiency and mistrust. As time passed, these failings left the Department of Transport reliant on a solitary, antiquated card printing machine—the only one of its kind serving the needs of millions.

This structural dependence proved catastrophic when that lone machine faltered again in February, halting the issuance of new driver’s licence cards across the country. Overnight, thousands of South Africans found themselves in a precarious legal position, their ability to drive suddenly suspended by a mechanical failure far beyond their control. The backlog of unprinted cards, already substantial before the breakdown, began to swell rapidly, trapping ordinary motorists in a bureaucratic limbo.

As the crisis deepened, the impact rippled through the daily lives of South Africans from all walks of life. Whether navigating Johannesburg’s crowded thoroughfares or winding coastal routes in KwaZulu-Natal, drivers carried not just passengers but the constant worry that their legal right to drive could be revoked at any moment. Licensing centres grew crowded with anxious citizens, while frustration mounted within government ranks. Minister Barbara Creecy, newly responsible for the embattled portfolio, responded unusually directly—acknowledging the scale of the problem and describing the department’s efforts to clear the backlog as a relentless, round-the-clock undertaking. Yet, every day, more licences expired, and the task remained Sisyphean in scope.

Numbers That Tell the Story: The Human Cost of Bureaucratic Breakdown

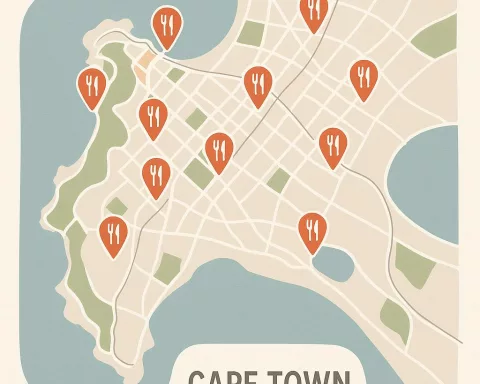

By July 2025, the data revealed the true magnitude of the crisis. More than 600,000 South Africans waited for their plastic driver’s licences—an administrative bottleneck of immense proportions. The province of Gauteng, always a focal point for both population growth and bureaucratic delays, bore the brunt of the crisis, with nearly 200,000 cards trapped in the queue. Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, both familiar with their own infrastructural challenges, followed closely in the tally of pending cards.

However, these statistics only scratch the surface of the issue. Each unprinted card symbolizes hours spent standing in lines, repeated visits to understaffed licensing facilities, and the constant anxiety about potential fines or legal trouble. The backlog is not just a logistical challenge; it has become a daily source of stress for hundreds of thousands. For many, a driver’s licence is not merely a plastic rectangle but a key to employment, independence, and social legitimacy.

Amid these difficulties, the Ministry sought new approaches to alleviate the crisis. Minister Creecy, eschewing bureaucratic delays, reached out to the Department of Home Affairs for assistance—a rare act of interdepartmental cooperation in a government often criticized for its siloed operations. The urgency of the request and the positive response from Home Affairs signaled a willingness to break from tradition and pursue creative solutions.

Innovation Amid Crisis: Collaborative Solutions and Technological Hurdles

The partnership between the Department of Transport and Home Affairs marked a pivotal shift in strategy. Rather than simply lending equipment, Home Affairs proposed to design and construct a prototype card printing machine specifically for Transport’s needs. This endeavor, both ambitious and steeped in South African traditions of improvisation, offered a path out of dependence on a single, aging machine. However, given the sensitive nature of identification documents, the State Security Agency must first approve the new technology—a process Minister Creecy publicly committed to completing within three months.

This effort to build new capacity recalls the resourcefulness that has long characterized South African society, particularly during periods of scarcity and challenge. The creation of a prototype machine represents not just a technical fix, but a reaffirmation of the country’s ability to adapt and innovate when circumstances demand it. Through collaboration and ingenuity, officials hope to restore the ability to provide timely, secure identification to citizens—a fundamental function of any modern state.

While the blueprint for the new machine moves through regulatory hurdles, the department has introduced practical stopgaps to shield motorists from the worst consequences of the backlog. Authorities have granted a six-month grace period for those whose licence cards have expired, acknowledging that the problem lies not with diligent citizens, but with systemic failures. Still, this grace is conditional—motorists must retain their renewal receipts to prove their status, and the temporary fix highlights the ever-present reliance on paperwork in South African daily life.

Everyday Realities: Adaptation, Resilience, and the Road Ahead

Beneath the surface of government announcements and statistical reports lies a tapestry of everyday struggles and small victories. In the minibus ranks of Soweto, taxi drivers exchange stories about their attempts to check on licence applications, flipping through thick wads of receipts. In Cape Town, a single mother anxiously awaits news from her local licensing office, her routine commute haunted by the risk of being stopped and fined. These individual stories bring the crisis into sharp focus, transforming abstract figures into lived experience.

This moment of crisis also serves as a reminder of South Africa’s long-standing tradition of finding creative solutions amid adversity. The concept of “bricolage”—making do with available resources—has shaped both its artistic output and its public administration. From township artists assembling works from found materials to jazz musicians improvising with what they have, the nation has cultivated a culture of adaptation that extends into the corridors of power. The prototype printing machine, crafted in response to pressing need, stands as a modern-day artifact of this enduring spirit.

Yet, the driver’s licence crisis is but one thread in a much larger pattern of public sector challenges. Instances of tender irregularities and procurement failures stretch far beyond Transport, touching sectors from energy to housing and social services. Each collapse in state capacity erodes public trust and underlines the importance of reform. The ongoing crisis around driver’s licences, though acute, is only the latest example of a deeper struggle to align aspiration with action in South Africa’s public administration.

Lessons and Opportunities: Building a More Responsive State

Despite the magnitude of these challenges, there are promising signs amidst the turmoil. The rapid response and willingness to seek help across departmental lines suggest a potential shift toward more effective governance. If sustained, such collaborations could become models for tackling other entrenched problems within the state. South Africa’s public sector, shaped by the legacies of colonialism and apartheid and tested by the demands of democracy, still holds considerable untapped potential for innovation and renewal.

At a foundational level, the crisis forces a broader reflection on the role of technology and documentation in modern governance. In an era where digital infrastructure underpins both security and convenience, the inability to produce a simple card highlights vulnerabilities that extend well beyond paperwork. Identification cards, driver’s licences, and passports are more than bureaucratic requirements—they are critical instruments of legal recognition, economic opportunity, and social inclusion.

Ultimately, the ongoing driver’s licence backlog weaves together stories of systemic dysfunction, everyday determination, and flashes of creative hope. The numbers may fluctuate and the actors may change, but the core question endures: How can South Africa transform its aspirations for efficient, reliable public service into tangible reality for its people? The answer lies, as always, in the interplay between state institutions, the resilience of ordinary citizens, and a collective willingness to build something better from the resources at hand.

FAQ: South Africa’s Driver’s Licence Crisis

What caused the driver’s licence crisis in South Africa?

The crisis stems from years of procurement failures and reliance on a single, outdated card printing machine. When this machine broke down in February 2025, over 600,000 licences stopped being printed, creating a massive backlog and leaving many drivers unable to renew their licences on time. This failure highlights broader systemic issues in government contract management and infrastructure maintenance.

How many South Africans are affected by the licence backlog?

By mid-2025, over 600,000 driver’s licences were unprinted nationwide. Gauteng province, the most populous, accounted for nearly 200,000 of these pending cards, with Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal also heavily impacted. The backlog affects millions indirectly, causing long queues at licensing centers and anxiety over legal driving status.

What steps is the government taking to resolve the crisis?

The Department of Transport, led by Minister Barbara Creecy, is collaborating with the Department of Home Affairs to design and build a new prototype card printing machine. This initiative aims to reduce reliance on the broken device. Additionally, a six-month grace period has been granted to drivers whose licences have expired, provided they keep their renewal receipts as proof. The new machine still requires security clearance before becoming operational.

Why is the driver’s licence printing process so vulnerable?

The vulnerability comes from dependence on a single, aging printing machine and a history of procurement irregularities that hindered upgrades or replacements. This bottleneck reflects deeper challenges in South Africa’s public sector, including inefficient tender processes and siloed government departments that have struggled to coordinate solutions promptly.

How is the licence backlog affecting everyday South Africans?

The backlog causes significant stress and inconvenience. Many have spent hours waiting in long queues at licensing centers, making repeated visits. For many, a valid driver’s licence is crucial for employment and mobility. Without it, drivers face legal uncertainties, potential fines, and loss of independence, impacting households and businesses across the country.

What does this crisis reveal about South Africa’s broader public administration challenges?

The driver’s licence crisis is symptomatic of longstanding systemic issues such as procurement failures, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and underinvestment in technology. However, it also highlights opportunities for reform, interdepartmental collaboration, and innovation. The government’s response—including the prototype printing machine and grace periods—reflects a willingness to adapt and improve public service delivery despite entrenched challenges.