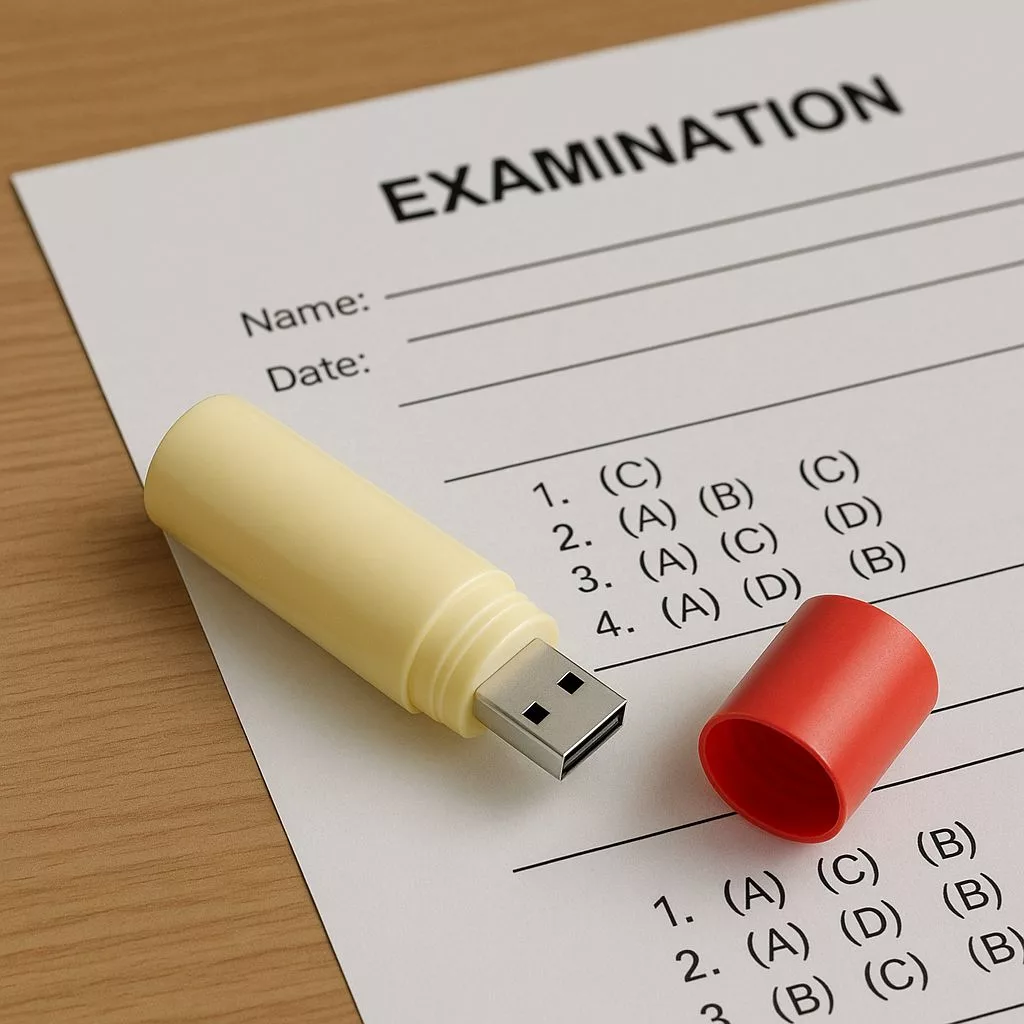

The 2025 South African Matric exam was leaked by a systems administrator named Lethola Mokoena. He copied the exam papers onto a special USB drive shaped like a lip-balm. Then, these secret papers were shared through WhatsApp and sold to students weeks before the actual test. This shocking event caused a big problem for the exams, making everyone wonder about safety and fairness.

How was the 2025 South African Matric exam leaked?

The 2025 South African Matric exam was leaked when a systems administrator, Lethola Mokoena, copied digital exam papers onto a USB drive disguised as a lip-balm. These papers were then distributed through WhatsApp and sold on other devices to students weeks before the official exam date.

1. Monday 21 October – The Moment the Wall Cracked

Most of Gauteng was still swallowing its first coffee when veteran marker Nokuthula Mbatha froze over essay number 207. The script began with a sentence that would not be legal to read until seven days later: “Shakespeare’s depiction of ambition finds its darkest echo in tomorrow’s elective governments…” By 08:15 the DBE’s internal server carried the code “E-P2 ANOMALY-001”. Before sunset, identical wording surfaced in 26 Maths and 11 Physical Sciences booklets. The most protected exam cycle since 1994 had been punctured from the inside.

The discovery ricocheted through the marking dome. Cluster supervisors sealed the row of tables, collected every booklet, and marched the markers to a quarantine room normally reserved for COVID-19 outbreaks. Scripts were photographed, bar-codes compared, and a statistics engine built by Umalusi and the CSIR calculated the probability of such overlap at 0.0003 %. The number was low enough to trigger Protocol 9C: total lock-down of the Vodacom marking centre, surrender of cell-phones, and sworn affidavits under the Protected Disclosures Act.

Within 24 hours the breach had a name: the “Tshwane leak”. Yet nobody knew where the pages had come from. The papers had been printed at 03:00 under SAPS guard, transported in GPS-tagged crates, and unsealed that morning by a double-lock system that needs a principal and a circuit manager to turn keys simultaneously. The only remaining possibility was that the leak had happened weeks earlier, while the masters were still digital.

2. Inside the Pipeline – A Castle Designed to be Impregnable

Understanding the heist means touring the fortress first. Eighteen months before pupils sharpen their HB pencils, item writers – retired teachers, university lecturers, subject advisers – gather inside Pretoria’s four-storey ATE campus. Air-gapped laptops generate questions; each file is encrypted with AES-256 keys split into three slivers held by the DBE director-general, the ATE campus manager, and an external audit firm.

Once questions are frozen, they move to an internal “Red Zone” server. The machine is isolated from the web yet reachable by 112 authorised staff through a fibre loop that also carries humdrum HR traffic. Printing happens in Midrand at 3 a.m.; police mark every crate with tamper seals and track them to 9 287 district vaults. On exam morning a principal and a DBE circuit manager must twist their keys together, cinema-style, to liberate the papers.

The 2025 breach skipped every one of these cinematic hurdles. Police escorts, GPS trackers and double padlocks were rendered useless because the papers left the building three weeks early, tucked into a 128-gigabyte thumb-drive painted to look like a lip-balm.

3. The Nine-Night Heist – How a USB Lip-Balm Drained the Vault

Forensic auditors have now rebuilt the timeline. On 30 September at 19:42 a folder called “SBA-Support” ballooned by 312 megabytes. CCTV shows Lethola “Lethu” Mokoena, a 29-year-old systems administrator, sliding a chrome-plated drive into Server Rack 12B. Mokoena had joined the DBE only eleven months earlier, seconded from the teacher-payroll section, and held Level-4 security clearance.

For the next nine evenings the same device surfaced on four separate machines. Each appearance lasted 37 seconds and coincided with a data spike that perfectly matched the byte-size of the 2025 English Home Language Paper 2, Mathematics Paper 1, and Physical Sciences Paper 2. By 04 October the master folder had been cloned into a WhatsApp group titled “Tshwane A-Team”, administered by Mokoena’s former roommate, 32-year-old tutor Sipho Nkosi.

From there the papers became nail-polish merchandise: crimson sticks for English, silver for Maths, gold for Science. A Soshanguve tuck-shop sold the devices for R350 each, smuggled inside empty lip-gloss canisters. Investigators have since retrieved 1 847 screenshots from 43 phones, proving that the same papers floated through iCloud drives, Telegram channels and even a 15-second Instagram reel that clocked 42 000 views before deletion.

4. Fallout, Courtrooms and the 700 000 Waiting Lists – What Happens Next

Seven schools in Tshwane North got the contraband earliest, among them Hoërskool Overkruin, Langabuya Secondary and Nellmapius. At Nellmapius the Physical Sciences HOD ran a “mastery clinic”: R100 bought you a brown envelope stamped “Open 27 Oct, 20:00”. Students re-photographed the sheets under orange light to wash out timestamps, then swapped summaries on Insta stories.

The law has since moved in. Criminal docket CAS 741/10/2025 lists charges under the Basic Education Act, the Prevention of Corrupt Activities Act and the Cyber Crimes Act. Mokoena and colleague Dimakatso Radebe surrendered passports after posting R10 000 bail each. The 26 learners whose scripts were isolated face Umalusi hearings that could void results for up to five years, citing the precedent set in the 2020 Maths Paper 2 leak when 46 candidates were ordered to rewrite.

Minister Gwarube has limited the national rewrite to the 26 implicated pupils, a decision equal-education groups call “statistical roulette”. Umalusi counters that a mass re-sit would cost R420 million and delay university registration. A compromise is emerging: a spot-verification oral for 1 200 pupils whose scores deviate more than 1.5 standard deviations from their mid-year average.

Meanwhile the DBE is spending R180 million on a 2026 security reboot: Faraday-caged server rooms, blockchain tokens for every question, biometric turnstiles that demand iris plus fingerprint, and AI models that flag any download burst above 50 megabytes. Random “canary” questions – fake items that glow like dye-packs – will help trace future leaks within minutes, not weeks.

For 700 000 honest candidates the finish line is still 15 December, when Umalusi must ratify results. Universities have agreed to delay registration by seven days; residence halls and NSFAS bursaries hang in the same balance. Hidden in the chaos is 18-year-old Anele Mngadi from Tsogo High, who rejected the leaked papers and reported the WhatsApp offer. Lobbyists want her rewarded with a full “Integrity Bursary”, proof that South Africa can celebrate honesty as loudly as it punishes greed.

[{“question”: “How was the 2025 South African Matric exam leaked?”, “answer”: “The 2025 South African Matric exam was leaked by a systems administrator named Lethola Mokoena. He copied the digital exam papers onto a USB drive disguised as a lip-balm. These papers were then shared through WhatsApp and sold to students weeks before the official examination date.”}, {“question”: “Who was responsible for the leak?”, “answer”: “Lethola Mokoena, a 29-year-old systems administrator seconded from the teacher-payroll section at the DBE, was identified as the individual who copied the exam papers. He had Level-4 security clearance.”}, {“question”: “When and how was the leak discovered?”, “answer”: “The leak was discovered on Monday, October 21st, when a veteran marker, Nokuthula Mbatha, noticed a sentence in an essay that was not supposed to be publicly known until seven days later. This led to an internal investigation, and by the end of the day, identical wording was found in 26 Maths and 11 Physical Sciences booklets, triggering a total lockdown and initiating the ‘Tshwane leak’ investigation.”}, {“question”: “How did the leaked papers circulate among students?”, “answer”: “After Mokoena copied the papers, they were transferred to a WhatsApp group titled ‘Tshwane A-Team,’ administered by his former roommate, Sipho Nkosi. From there, the papers were sold to students, often disguised as lip-gloss canisters, for R350 each. They also circulated through iCloud drives, Telegram channels, and even a 15-second Instagram reel.”}, {“question”: “What legal and academic consequences have arisen from the leak?”, “answer”: “A criminal docket (CAS 741/10/2025) has been opened, listing charges under the Basic Education Act, the Prevention of Corrupt Activities Act, and the Cyber Crimes Act. Mokoena and Dimakatso Radebe surrendered their passports after posting R10,000 bail each. The 26 learners whose scripts were isolated face Umalusi hearings that could void their results for up to five years. While a mass re-sit was considered, it was deemed too costly and disruptive, leading to a compromise of a spot-verification oral for 1,200 pupils with significantly deviated scores.”}, {“question”: “What measures are being implemented to prevent future leaks?”, “answer”: “The DBE is investing R180 million in a 2026 security reboot. This includes Faraday-caged server rooms, blockchain tokens for every question, biometric turnstiles requiring iris and fingerprint scans, and AI models to flag large download bursts. Additionally, random ‘canary’ questions will be introduced to help trace future leaks quickly.”}]