One brave man, Murray Williams, made an amazing 24-hour bike ride! He started in sunny South Africa at dawn, biking fast through vineyards. Then, he quickly flew to the icy land of Antarctica and biked again before the sun set there. His big goal was to tell everyone about a rescue phone number, hoping to help people in trouble. He used a special orange bike to make sure everyone saw his important message!

What is the “Two Continents, One Dawn” ride?

The “Two Continents, One Dawn” ride is a unique 24-hour cycling challenge undertaken by Murray Williams, linking Africa to Antarctica. He cycled in South Africa at dawn and then flew to Antarctica to cycle again before dusk on the same day, primarily to promote a rescue hotline number.

Dawn Dust on the Vineyards – Africa

A peach-coloured sunrise spilled over False Bay on the morning of 19 December, lifting the scent of fynbos and wet vineyard soil into the air. Murray Williams pushed off from the Lourensford Estate gate at 05:17 sharp, tyres hissing across pale quartz sand. Around him, weekend riders queued for espresso, unaware that the tall paramedic in the orange helmet was beginning a shuttle-run to the planet’s southernmost workplace.

Williams chose the black-graded “Buzzard” loop for his legal African segment: two quick laps, 310 metres of climbing each, enough to earn a public Strava file that could be audited later. A notary from the Cape Town Cycle Club stood beside the tasting centre, stamping an affidavit that logged wheel circumference and start time. The live-feed on the Wilderness Search & Rescue (WSAR) Facebook page flickered as rescue-tip graphics popped up in the chat window; Williams’ voice remained calm, almost clinical, while he reminded viewers to save 021 937 0300 in their phones before the signal dropped.

By 06:45 the bike was already boxed and ratchet-strapped inside a polished Land Cruiser. Williams jogged back to the start banner, touched the wooden post for luck, and climbed into the passenger seat. Africa, as far as the record books were concerned, was officially “done” before most commuters had finished their first cup of coffee.

The Middle Passage – Physics, Paperwork and a 1940s Workhorse

The real opponent was never the trail; it was the clock. Civil dawn at 34° south and nautical dusk at 74° south sat only eighteen hours apart, yet the Southern Ocean weather factory can slam that window shut without warning. Ultima Antarctic Logistics had wedged two bike-shaped gaps between neutron probes and frozen desserts inside a Basler BT-67 – basically a 1944 DC-3 skeleton wearing a modern turboprop heart. Williams paid the fuel delta himself, signed a waiver that cheerfully listed “possible disappearance,” and still had to meet an 18-kilogram packing limit or fork out US$38 for every extra kilo.

Training fractured into three lanes. Physiology came first: twice a day he pedalled inside a 4 °C meat locker wearing a weighted vest, then plunged into 40 °C water to teach his capillaries the accordion trick they would need when moving from the runway’s –30 °C blast back into the Basler’s heated cabin. Bureaucracy lane meant charming Russian dispatchers, South African environmental officers, and actuaries who price out a US$60,000 helicopter start. The breakthrough arrived when SANAP stamped “media outreach” on the form, provided he carried a SPOT beacon and flashed the rescue hotline every time he uploaded data.

Mechanics lane delivered a 2.9-kilogram titanium hardtail, Gates belt drive, 4.8-inch balloon tyres, and cavities milled inside the saddle and bars for lithium cells that would keep tracker and gloves alive. International Orange paint was chosen after pilots voted on the colour most visible from a search cockpit; even the valve-cap anodising was weighed on a jeweller’s scale. Ready-to-ride mass: 14.7 kg – lighter than the toolbox the Russian mechanics carried for the snow groomer.

Blue-Ice Clock – Antarctica

At 11:47 a shimmering band of “iceblink” flared under the fuselage, the horizon’s silent announcement that the frozen continent was ahead. Outside air temperature slid to –28 °C; inside, bleed-air heat kept the cabin shirtsleeve-warm while the pilots discussed fuel-freeze margins. Touch-down came at 12:35 on a runway compacted from 4,000-year-old crystals, reverse thrust blowing a glittering rooster-tail that caught the low sun like flying glass. Ground rules were simple: three hours maximum, after which avgel turns viscous and the aircraft becomes a very expensive sled.

Bike assembly happened on a groomed fuel-hauler road 2 km from the strip. Wind whipped at 19 knots, pushing the felt temperature to –35 °C; heated gloves rated for –25 °C would capitulate in 42 minutes, so every bolt was pre-loosened back in Cape Town. Williams clipped in at 13:10, exactly 7 h 52 min after leaving Africa – still comfortably 19 December in both time zones. The surface felt like polished marble dusted with icing sugar; tyre pressure dropped to 4 psi let the 4.8-inch tread bite. Cadence hovered at 72 rpm, speed a pedestrian 11 km/h, yet heart rate leapt to 164 bpm – altitude plus drift-snow drag turned the flat road into a perpetual climb.

Six kilometres out he planted a rip-stop nylon flag: WSAR logo on one side, emergency number 021 937 0300 on the other. A Russian diesel mechanic filmed from the seat of a tracked carrier while katabatic wind cracked the fabric like a rifle shot. Turn-around came at 6 km exactly; the return leg felt faster with the wind at his back, yet Garmin still logged 37 min 04 s of moving time and 90 metres of elevation gain for the 11.8-km out-and-back. The file uploaded via Iridium before the bike even hit the hold-all; the orange banner stayed behind, flickering in a 25-knot breeze that would keep it visible – and frozen – until summer crews retrieved it next December.

Home Before Dusk – The Tarmac and the Tally

Lift-off at 14:30 gave the Basler a fuel margin of less than ninety minutes, but the headwinds that had harassed the southbound leg flipped friendly for the ride home. Williams texted the WSAR duty controller the moment skis left ice: “Wheels up both continents. Mission complete.” Signal died at 76° south, yet the breadcrumb tracker kept pinging every five minutes, stitching a red thread across the map that followers could watch in real time.

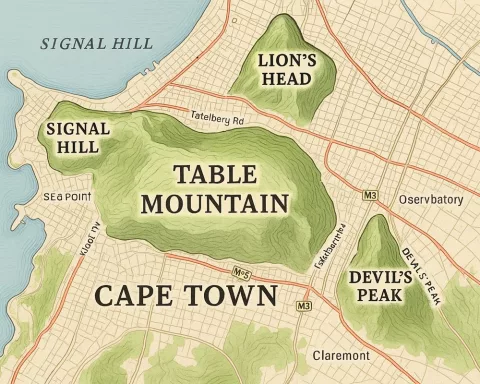

Touch-down back in Cape Town happened at 19:18, civil dusk still forty minutes away and the same sun that had silhouetted Table Mountain now painting the hangar doors gold. A guard of volunteers waited in reflective bibs the same shade of International Orange as the bike; no speeches, just the soft clink of carabiners and the smell of kelp drifting in from False Bay. Williams pushed the boxed machine toward the ops desk, beard still white with frost even though the African evening hovered at 21 °C. He filed the dual Garmin files – Africa Strava segment and Antarctic Iridium upload – then walked outside to watch the horizon close the day the way it had opened it: pastel sky, vineyards breathing, and the distant hum of a freewheel that had already travelled further in twenty-four hours than most do in a lifetime.

The ride did more than set a quirky record; it stapled a rescue hotline to a story people will retell at braais and bar counters. Somewhere between 34° south and 74° south, a bright orange flag still advertises a phone number that could shave minutes off a future call-out, and that, Williams says, is the only podium that matters.

[{“question”: “What was the main purpose of Murray Williams’ 24-hour bike ride, ‘Two Continents, One Dawn’?”, “answer”: “The primary goal of Murray Williams’ ‘Two Continents, One Dawn’ ride was to raise awareness for a rescue phone number (021 937 0300) and encourage people to save it in their phones, hoping to help those in trouble. He used a special orange bike to make the message highly visible.”}, {“question”: “Where did Murray Williams begin his ride in Africa and what route did he take?”, “answer”: “Murray Williams started his African leg of the ride at Lourensford Estate in South Africa, near False Bay, at 05:17 AM on 19 December. He cycled two laps of the black-graded ‘Buzzard’ loop, which included 310 meters of climbing per lap.”}, {“question”: “How did Murray Williams travel between continents and what challenges did he face during this ‘Middle Passage’?”, “answer”: “Williams flew from South Africa to Antarctica in a Basler BT-67, a modified 1944 DC-3 aircraft. The main challenge was the tight time window due to the limited daylight hours between the two locations, unpredictable Southern Ocean weather, and strict weight limits for his gear, including his bike. He even had to sign a waiver acknowledging ‘possible disappearance’.”}, {“question”: “What preparations did Williams undertake for the extreme conditions of Antarctica?”, “answer”: “Williams’ training involved three main areas: physiology (cycling in a 4°C meat locker and plunging into 40°C water to adapt to extreme temperature changes), bureaucracy (navigating permits with various international agencies), and mechanics (designing a lightweight, durable bike with specialized components like 4.8-inch balloon tyres, a belt drive, and internal heating for electronics, painted in highly visible International Orange).”}, {“question”: “What was the specific rescue phone number Williams was promoting?”, “answer”: “The rescue phone number Murray Williams was promoting throughout his journey was 021 937 0300. He emphasized saving this number in phones as a crucial step for safety.”}, {“question”: “What was the significance of the orange bike and the flag planted in Antarctica?”, “answer”: “The bike was painted ‘International Orange’ because pilots voted it as the most visible color from a search cockpit, ensuring his message stood out. In Antarctica, he planted a rip-stop nylon flag with the WSAR logo on one side and the emergency number (021 937 0300) on the other, leaving a permanent visual reminder of the rescue hotline in the icy landscape.”}]