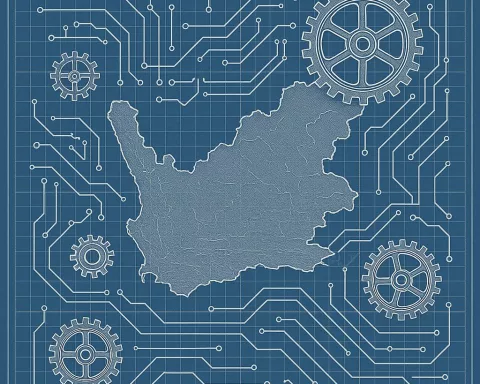

{“summary”: “The Western Cape is building a \”digital twin\” of its public buildings and roads. This means creating a live, digital copy that uses sensors and data to predict problems and help with planning. It all started with a small grant of €97,500, showing how even a little money can kickstart big changes. This project will help the province manage its infrastructure better, making things last longer and run more smoothly.“}

What is the Western Cape’s Digital Twin project?

The Western Cape’s Digital Twin project is an ambitious initiative to create a living, breathing digital replica of the province’s public infrastructure. It integrates physical data from buildings, roads, and pipes with sensors and rules to simulate scenarios, optimize maintenance, and inform urban planning, funded initially by a €97,500 EU grant.

A Suitcase-Sized Grant That Can Carry a Province

In February 2024 an A4 envelope left Brussels and landed on the desk of the Western Cape’s infrastructure chief. The slip of paper inside promised €97 500 – about the price of a mid-range BMW – yet the provincial government greeted it like winning lottery ticket. The modest sum is the seed capital for “Towards a Digital Twin Province”, an ambitious programme that wants to wire every public building, road and pipe into one living, breathing digital mirror. The channel is the EU’s Dialogue Facility 3.0, the final slice of a €30 million technical-assistance pool that previously helped South Africa write its carbon-tax law and ocean-management rules. For the first time a province, not National Treasury, is the signatory – proof that sub-national governments are now the speedboats of African public-sector reform.

The Department of Infrastructure (DOI) oversees R19 billion worth of roofs, courts, schools and hospitals; €97 500 is loose change against that backdrop. Yet the money is pure oxygen for the boring-but-vital layer that usually kills mega-projects: standards, software licences, cloud credits and governance playbooks. Those euros will underwrite the first eighteen months of design, a reference scan of 150 “sentinel” buildings and the procurement templates needed to scale to the full 28 000 facility estate. In EU-speak the grant is classed as “non-repayable technical assistance”; in Cape Town slang it is simply the cheat-code that turns concrete into code without another begging-bowl trip to the National fiscus.

What a Digital Twin Means Down South

Forget glossy renderings that collect dust on a planner’s shelf. In the Western Cape a digital twin is a four-layer organism that updates itself while you sleep. Layer one, the Shape tier, is a millimetre-accurate skin built from drone LiDAR, backpack scanners and crowd-sourced phone photos. Layer two, State, is a fire-hose of cheap IoT sensors pushing vibration, humidity, energy and leak data into an open MQTT broker. Layer three, Rules, is a graph database that remembers every bolt, by-law and maintenance receipt; it knows which window still has a valid warranty and which ramp fails the 2011 disability code. Layer four, Scenario, is a GPU-powered crystal ball that stress-tests the asset against floods, budget cuts or heatwaves before a single brick is ordered.

The €97 500 will not scan every school toilet; it will pay for the architecture, data dictionaries and a proof-of-concept covering 150 strategically chosen buildings: a 1920s Cape-Dutch magistrate’s court, a 1970s brutalist hospital, a 2000s prefab primary school and 2019 cross-laminated-timber flats. Those sentinels give the province a typological spread wide enough to debug the system before the real tsunami of data arrives. If the standards hold, subsequent scanning sorties can be crowd-funded, bond-financed or baked into maintenance tenders without re-inventing the wheel.

Estonia: The Unlikely Fairy Godparent

Hidden in Annex 3 of the grant agreement is a clause that forces the Western Cape to co-write every standard with Estonia’s e-Governance Academy. The Baltic state – population 1.3 million – already runs the world’s most advanced state-owned twin: the €70 million “e-Estonia KSR” covers every road, school and title deed back to 1993. Two pieces of Estonian wizardry will be copy-pasted straight into the Cape. First is the X-Road twin connector, a zero-trust data highway that lets the province pull vendor invoices from National Treasury’s BAS accounting system without ever duplicating sensitive files. Second is the SILK compression codec, an algorithm that trims point-cloud data by 83 %, allowing a township clinic to be captured over a 4 G link and stored on a dust-proof Raspberry Pi.

The deal is not one-way traffic. The Western Cape will hand over its “thermal poverty map”, a machine-learning model that fuses satellite heat-loss imagery with census income data to spot roofs most in need of insulation – analytics Estonia now craves as it wrestles with Nordic winter-energy shortages. The exchange is a reminder that in the digital era the global South can sometimes ship innovation north instead of the other way around.

Hardware, Backpacks and Phone Swarms

Fieldwork began on 1 March 2024 when GeoPulse Survey, a woman-run SME, flung a DJI Matrice 300 over Beaufort-West’s 126-year-old magistrate’s court. The drone’s LiDAR puck fired half a million points per second while a 45-MP camera grabbed texture. Indoors, surveyors strapped on a NavVis VLX backpack that looks like rejected Ghostbusters kit yet delivers 2 mm accuracy at strolling pace. Citizens were invited to play too: the open-source Polycam app stitched 2 500 phone snaps into a 10 cm mesh; learners from COSAT science school in Khayelitsha earned R5 000 airtime and a tour of the drone hangar for uploading 1.2 GB of corridor data.

All captures land on an Azure Data Box Edge bolted to a 200 W solar trailer. Where the grid fades, LoRa repeaters clipped to lampposts ferry the last mile. The result is a scanning ecosystem that can survive load-shedding, bandwidth deserts and tight budgets – conditions that would sink a conventional metro-wide survey.

Who Owns the Pixels?

Raw point clouds are gifted to the public under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 – anyone can remix them as long as the work stays non-commercial and open. Derived analytics – energy baselines, seismic fragility curves – sit on the provincial Open Data Portal but require a free login to stop tender sharks from gaming the numbers. Faces, licence plates and Wi-Fi probe requests are blurred on-device by a YOLOv7 nano model before upload; the hashing of every file to the LTO blockchain every 30 seconds creates a tamper-evident chain that future corruption investigators will bless. A privacy-impact assessment signed by the provincial Information Officer binds every partner to POPIA and GDPR equivalency, so personal data never becomes political ammunition.

Paying for the Party After the Grant Runs Dry

Seventy-five grand buys standards and swagger, not 28 000 building scans. The DOI’s CFO has sketched a three-phase finance ladder. Phase 1 (2024-25) diverts R12 million from the “routine maintenance” budget line, justified by studies showing digital twins chop forensic audit costs by a third. Phase 2 (2025-27) issues a R150 million green bond certified by the Climate Bonds Initiative; coupons are serviced by verified electricity-savings contracts pegged at 0.8 kWh/m²/year. Phase 3 (2027-30) unlocks land-value capture: developers along the Tygerberg well-field corridor can earn an extra 0.5 floor-area ratio if they bankroll twin nodes – sensors and edge servers – in their basements. Estonian pension funds have already signalled appetite for the rand-denominated paper, hunting for 5 % green exposure that carries a juicy emerging-market kicker.

From Bricklayer to Data Steward

Technology is only 20 % of the recipe; the rest is people. A SETA discretionary grant will upskill 300 artisans into “digital stewards” over three years. Bricklayers learn to tag corbel cracks in Autodesk Tandem; plumbers install LoRaWAN leak sensors; clerks morph into PostgreSQL curators. Every micro-credential is hashed to a blockchain wallet the worker carries if they later move to Gauteng – or Tallinn. The EU grant demands 40 % female participation; the first cohort is already 52 % women, led by former meter-reader Nontando Mbuli whose Python script auto-detects water-meter tampering with 94 % accuracy, saving the province millions in lost revenue.

Quick Victories in Three Iconic Buildings

Within three weeks the twin served three piping-hot wins. At George Regional Hospital a GPU simulation showed that shoving the chemotherapy ward to the north block would slice HVAC energy by 18 % by riding the passive stack effect; the move is on the June 2024 build schedule. Langa High School’s new vibration sensors felt after-hours tremors that led inspectors to an illegal basement nightclub; eviction is forecast to save R2.3 million in cracked-slab lawsuits. Over at the Provincial Archives in Roeland Street humidity micro-clusters revealed a 7 % RH spike every Sunday; a rogue swamp cooler was fixed, sparing 1.2 linear kilometres of 19th-century slave-registry papers from archival mould and a public-relations nightmare.

Spectrum, Power Cuts and Trust Deficits

No good story is complete without dragons. The twin gulps 4 TB a week, but regulator ICASA has issued only experimental 6 GHz licences to two metros. The province has applied for a dedicated “Internet of Government” spectrum block, invoking disaster-management override clauses. Eskom’s stage-6 darkness starves edge servers for up to six hours; lithium buffers fade after 45 minutes. The workaround is a scavenger’s dream – 100 Ah second-life EV batteries harvested from scrapped Metrorail buses give four-hour autonomy at one-third the price of fresh lead-acid packs. Meanwhile, informal traders side-eye drones as covert tax collectors. The DOI counters with monthly “scan-and-braai” gatherings: residents watch their shacks appear on screen, walk away with free roof-insulation tips and a 3-D printed key-ring of their home – alchemy that converts sceptics into street-level evangelists.

Laws Rewritten by the Twin

Data is power, and power soon drafts its own rules. A draft Infrastructure Data Bill – open for public comment until 15 September 2024 – makes a digital handover mandatory for every new state building. BIM models, sensor schedules and asset tags must be uploaded before the occupancy certificate is signed; non-compliance triggers a 2 % retention penalty – small enough to survive constitutional scrutiny, large enough to change behaviour. An amendment to the Western Cape Planning and Development Act inserts a “digital servitude” clause: any private development within 500 m of strategic state infrastructure must share survey-grade models, ensuring the twin stays evergreen long after the ribbon-cutting champagne dries.

Spill-overs, Leapfrogs and Green Side-quests

Gauteng’s infrastructure department has already asked for the open-source playbook and will pilot its own twin on the R4.5 billion Tshwane judicial precinct. Mpumalanga, broke but ambitious, wants to skip LiDAR altogether and generate “synthetic twins” with AI-drawn 3-D meshes from 2-D photos – an 80 % solution at 10 % cost that could force the Western Cape to justify its premium-accuracy approach. Minister Simmers has quietly widened the twin’s remit to “green-grey infrastructure”; drones now calculate vegetation stress so that Working for Water teams can target invading eucalyptus with chainsaw precision. Clear one hectare of aliens and the Berg River gains 43 000 extra litres a day – R1.2 billion in avoided dam-expansion bills over 30 years, proving that pixels can pay for pipes.

Smell, Self-healing Concrete and Quantum Keys

The future queue is already visible. Nano-MOS e-nose sensors that sniff mould spores and sewer gas will plug into the twin in Q2 2025. Self-healing concrete laced with limestone-producing bacteria is on trial; ultrasonic probes will watch cracks seal themselves. Estonian cryptographers have pre-loaded CRYSTALS-Kyber quantum-safe keys so that sensor packets stay unreadable once quantum computers crack RSA – insurance against a 4 096-logical-qubit monster that may still be a decade away but will not wait for bureaucrats to upgrade.

A Province That Thinks in Real Time

By 2030 the Western Cape twin will not be a single dashboard in a control room; it will be a living nervous system that smells, sees and heals itself. Every roof insulation grant, every riot heat-map, every cracked dam wall will feed back into simulations that refine the next budget, the next by-law, the next job ad. The €97 500 that arrived in a plain envelope is the butterfly wing-flap that sets a province-sized storm of data, skills and opportunity in motion – proving that in the digital age the smallest grant can carry the heaviest briefcase of change.

[{“question”: “What is the Western Cape’s Digital Twin project?”, “answer”: “The Western Cape’s Digital Twin project is an ambitious initiative to create a living, breathing digital replica of the province’s public infrastructure. It integrates physical data from buildings, roads, and pipes with sensors and rules to simulate scenarios, optimize maintenance, and inform urban planning. This project aims to make infrastructure last longer and run more smoothly by using real-time data and predictive analytics. It was initially funded by a modest €97,500 grant from the EU’s Dialogue Facility 3.0.”}, {“question”: “How did the project get started with such a small amount of funding?”, “answer”: “The project began with a €97,500 grant from the EU’s Dialogue Facility 3.0. While this amount is small compared to the province’s overall infrastructure budget, it was crucial for funding the ‘boring-but-vital’ aspects of the project, such as developing standards, acquiring software licenses, securing cloud credits, and establishing governance playbooks. This initial sum will cover the first eighteen months of design, a reference scan of 150 ‘sentinel’ buildings, and the procurement templates needed to scale the project to the full 28,000 facilities.”}, {“question”: “What are the four layers of the Western Cape’s Digital Twin?”, “answer”: “The Western Cape’s Digital Twin is built on a four-layer organism designed for continuous updates:\n\n Shape: This layer provides a millimeter-accurate skin of the infrastructure, created using drone LiDAR, backpack scanners, and crowd-sourced phone photos.\n State: This layer collects real-time data from cheap IoT sensors (vibration, humidity, energy, leaks) and feeds it into an open MQTT broker.\n Rules: A graph database in this layer stores every detail, from bolts and by-laws to maintenance receipts, knowing the warranty status of components and compliance with codes.\n Scenario: This GPU-powered ‘crystal ball’ layer stress-tests assets against various scenarios like floods, budget cuts, or heatwaves to predict outcomes before physical changes are made.”}, {“question”: “How is Estonia involved in the project?”, “answer”: “Estonia’s e-Governance Academy is a key partner, co-writing every standard for the Western Cape’s Digital Twin. Estonia, known for its advanced state-owned digital twin, e-Estonia KSR, is sharing two crucial technologies: the X-Road twin connector for secure data exchange with entities like National Treasury, and the SILK compression codec, which significantly reduces point-cloud data size, enabling efficient data capture and storage even in areas with limited connectivity. In return, the Western Cape will share its ‘thermal poverty map’ analytics, which identifies areas most in need of insulation, benefiting Estonia’s efforts to address winter-energy shortages.”}, {“question”: “How will the project be funded after the initial grant runs out?”, “answer”: “The Department of Infrastructure’s CFO has outlined a three-phase financing plan:\n\n Phase 1 (2024-25): R12 million will be diverted from the ‘routine maintenance’ budget, justified by expected savings in forensic audit costs.\n Phase 2 (2025-27): A R150 million green bond, certified by the Climate Bonds Initiative, will be issued. The coupons for this bond will be serviced by verified electricity-savings contracts.\n Phase 3 (2027-30): This phase will involve land-value capture, where developers in specific corridors can gain extra floor-area ratio if they invest in twin nodes (sensors and edge servers) within their developments.”}, {“question”: “What challenges does the Digital Twin project face, and how are they being addressed?”, “answer”: “The project faces several challenges, including:\n\n Data Volume and Spectrum: The twin generates 4 TB of data weekly, but regulator ICASA has only issued experimental 6 GHz licenses. The province has applied for a dedicated ‘Internet of Government’ spectrum block.\n Power Cuts (Load-shedding): Eskom’s power cuts impact edge servers. The solution involves using 100 Ah second-life EV batteries from scrapped Metrorail buses, providing four hours of autonomy at a lower cost than new batteries.\n Public Trust: Some informal traders view drones with suspicion. The Department of Infrastructure addresses this through ‘scan-and-braai’ gatherings, where residents can see their homes on screen, receive free roof-insulation tips, and get 3D-printed keyrings of their homes, building trust and engagement.”}]