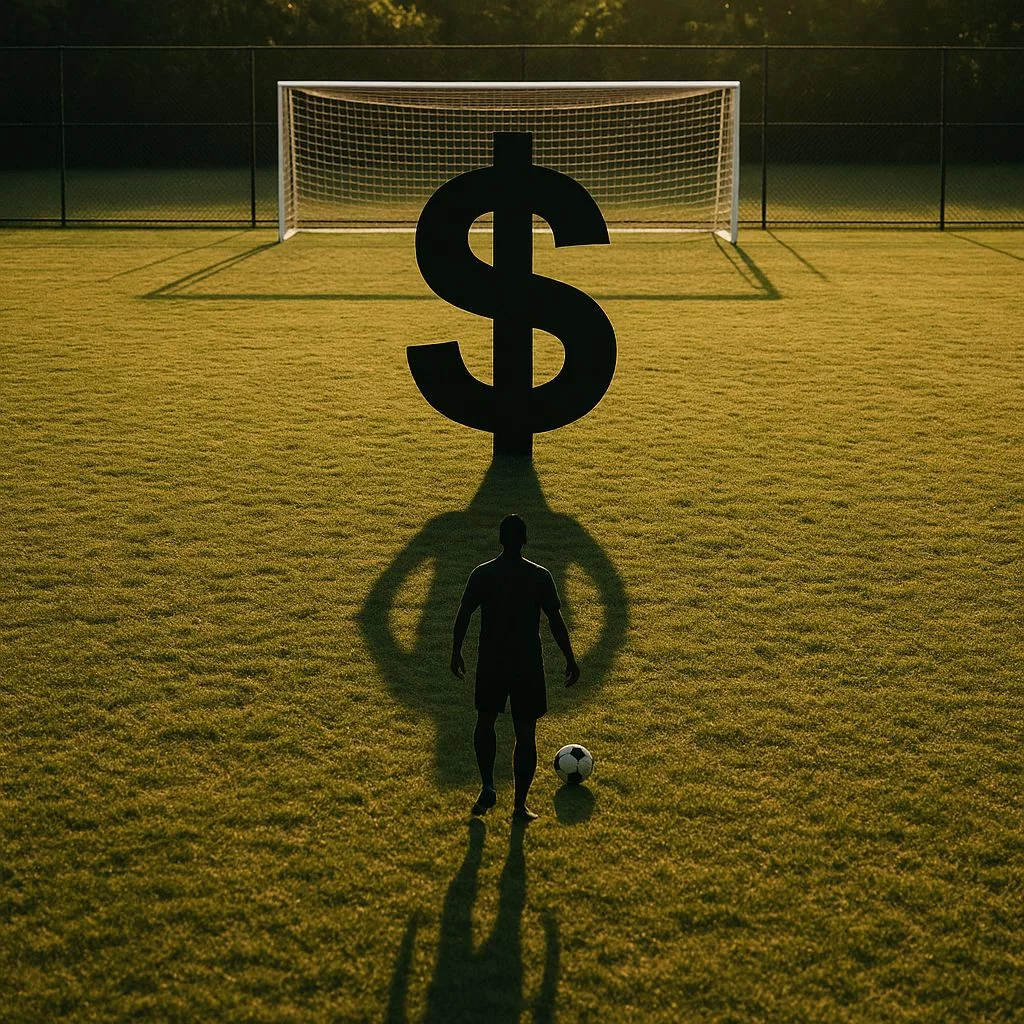

Adriaan Richter, a 1995 Springbok rugby hero, had to auction his World Cup medal because life tackled him hard. After business dreams crashed and debts piled up, that shining medal became his last hope. It wasn’t just gold; it was a lifeline, sold to cover his children’s school fees and keep his family afloat. This once-proud symbol of victory became a stark reminder of life’s tough scrums, showing how even a hero’s glory can turn into groceries.

Why did a 1995 Springbok rugby medal end up being auctioned?

Adriaan Richter, a 1995 Springbok rugby player, auctioned his World Cup medal due to severe financial distress. After various business failures, including mining gear sales, farming, and a tool-hire franchise, he faced mounting debts, school-fee arrears, and a meager rugby annuity, making the medal his last valuable asset.

1. Ellis Park, 24 June 1995 – A Whisper in a Tunnel

The final whistle had barely finished shaking the posts when a damp concrete corridor swallowed the Springbok pack. A wooden fruit-box stuffed with sparkling disks waited on a plastic table. No ceremony, no cameras – just a volunteer handing out cheap blue pouches while security guards smoked against the wall. Adriaan Richter tucked the gilt coin inside his sock, terrified it would slip through the drain of celebration.

That night he drilled two pin-holes through the ribbon so his toddler could parade it at pre-school dress-up days. The pouch vanished within a season; the ribbon frayed like old lace; the disk itself collected a hair-line scratch where it rattled against Toyota keys on the bedside table. What started as proof of masculinity ended, almost three decades later, as the only negotiable asset in a house groaning with red-ink statements.

When the gavel struck, the crack travelled farther than the auction-room walls. It ricocheted back through every ruck, every bar-room handshake, every chorus of Shosholoza that once floated above the upper tier. The new custodian got a numbered lot; Richter kept the echo – and the school-fee arrears.

2. Balance Sheets That Tackle From Behind

The slide was never a single spear-tackle – it resembled one of those interminable scrums that wheel through four reset calls. Thirty-four Tests, one winter at Leicester for £450 a Saturday, and a suitcase of pounds that melted against a wobbling rand. The cash bought physiotherapy for knees that still pop like bubble-wrap on cold mornings.

He came home to sell yellow-metal mining gear on hire-purchase; 2008 shredded commissions overnight. He swapped spreadsheets for 200 hectares of maize outside Delmas; a single hail-grenade in 2012 turned silks into silage. A tool-hire franchise followed; customers defected to Chinese knock-offs sold for cash at taxi ranks. Each venture peeled back another layer of collateral signed when optimism was tax-deductible.

By lockdown 2020 the arithmetic was merciless: two boarding-school invoices equalled the after-tax annuity SARU dribbled out – R9 800. The Navara that once carried Craven Week hopefuls went to a Zimbabwean farmer for spot-rand; match-worn jerseys fetched R1 500 apiece from nostalgic expats in Dubai. The medal was the final negotiable relic, the last tangible thing that still carried compound interest of the heart.

3. The Strange Economy of Bronze, Silver and Story

South Africans will pay eye-watering prices for ghosts: Piet Visagie’s 1970 jersey, Joost’s 1999 studs, even a tooth-marked mouthguard said to belong to James Small. Yet winners’ medals almost never surface. Rugby heroes hoard them the way retired Marines guard Purple Hearts; scarcity breeds suspicion rather than frenzy.

When Richter consigned, the room knew distress like a blood-smelling shark. Rael Levitt set the reserve at fifty grand; 87 seconds of telephone ping-pong nudged it to sixty-two-five. The ledger calls the buyer “Sharks 15” – no face, no Instagram handle, just a Durban area code and a courier bag. Experts mutter that a Pienaar or Stransky disk would have doubled the tally; a flanker who started twice in the pool stages lives in the memorabilia hinterland, adored but not posterised.

Replicas sprouted overnight at R1 900 a pop, blurred just enough to dodge trademark lawyers. A mining house ordered forty, laser-etched its own crest on the reverse and handed them out at a “Madiba-themed” team-build. The real metal is only 65 g of silver washed with gold – melt value about eighteen hundred rand. The rest is pure narrative, the same dark magic that lets a Picasso canvas outrun the cost of pigment.

4. Safe-Deposit Boxes Cannot Store Smell

The disk now rests in nitrogen-filled perspex at 18 °C and 45 % humidity, couriered between mall pop-ups sponsored by Swiss watch brands. Visitors scan a QR code, pose beside the sparkle, drift out through a jewellery store. The plaque reads: “Final player medal, A. Richter, 1995.” No mention of school fees, hailstorms, or knees that click like clockwork every dawn.

Inside the current Springbok camp the story arrived like a wet high-ball. Rookie millionaires ring the Players’ Association demanding pension schemes and crypto-proof disability cover. Planners quote seven-year career spans and the miracle of compound interest; nobody mentions the scent of deep-heat and cut grass that once clung to a strip of ribbon.

Richter’s teenager keeps a torn towel scrap stained with blood from the Canada match – mom dated it with a laundry marker and sealed it in a sandwich bag. It is worthless at auction, and therefore safe from auction. The father still owns the memory of Nelson Mandela’s handshake, the baritone thank-you for “uniting our people.” The buyer owns the metal; the metal owns the story; the story, for now, owns us.

1. Why did Adriaan Richter auction his 1995 Springbok World Cup medal?

Adriaan Richter, a 1995 Springbok rugby hero, auctioned his World Cup medal because he faced severe financial difficulties. After several business ventures failed, including mining equipment sales, farming, and a tool-hire franchise, he accumulated significant debts. The sale of the medal was a last resort to cover his children’s school fees and support his family.

2. What was the initial experience of receiving the World Cup medal like for Adriaan Richter?

The medals were distributed in a rather unceremonious manner in a damp concrete corridor after the final game. There was no grand ceremony or cameras; a volunteer handed them out from a wooden fruit box. Adriaan Richter initially tucked his medal into his sock, later drilling holes in the ribbon for his toddler to play with it, highlighting its early status as a personal memento rather than a highly valued artifact.

3. What were some of the business ventures Adriaan Richter pursued after his rugby career?

After his rugby career, Richter attempted various businesses. These included selling yellow-metal mining gear, farming 200 hectares of maize, and owning a tool-hire franchise. Unfortunately, these ventures were largely unsuccessful, leading to significant financial losses and mounting debt.

4. How much is the actual gold and silver content of the medal worth?

The medal itself, made of 65 grams of silver washed with gold, has a melt value of approximately eighteen hundred rand. The significantly higher auction price reflects the medal’s historical and narrative value rather than its intrinsic material worth.

5. What is the current status and location of Adriaan Richter’s auctioned medal?

The medal is now housed in a nitrogen-filled perspex case at 18°C and 45% humidity, often displayed at mall pop-ups sponsored by Swiss watch brands. It’s presented with a plaque identifying it as “Final player medal, A. Richter, 1995,” without mention of the personal struggles that led to its sale.

6. How does the current generation of Springbok players view their financial future compared to past heroes?

The story of Richter’s auctioned medal has influenced current Springbok players, who are now reportedly demanding more robust pension schemes and crypto-proof disability cover from the Players’ Association. This indicates a growing awareness among modern rugby professionals about securing their financial futures beyond their playing careers, learning from the challenges faced by past heroes like Richter.