At Swartklip Road in Cape Town, many people connect to electricity illegally because formal power is too expensive or hard to get. They rig unsafe cables that bring power but also risk electrocution and damage to a vital pump station. When the pump breaks down, sewage overflows, creating serious health problems for the whole community. City officials try to balance enforcing rules with understanding residents’ struggles, but the deeper challenge is building trustworthy, lasting services for everyone. This story shows how survival and risk live side by side in Cape Town’s informal neighborhoods.

Why do residents at Swartklip Road make illegal electricity connections?

Residents at Swartklip Road create illegal electricity connections due to limited or unaffordable formal supply. These makeshift links provide immediate access to power but pose serious risks like electrocution, pump station failure, and sewage overflow, affecting public health and infrastructure stability in Cape Town’s informal settlements.

The Pulse of Swartklip: Infrastructure on the Margins

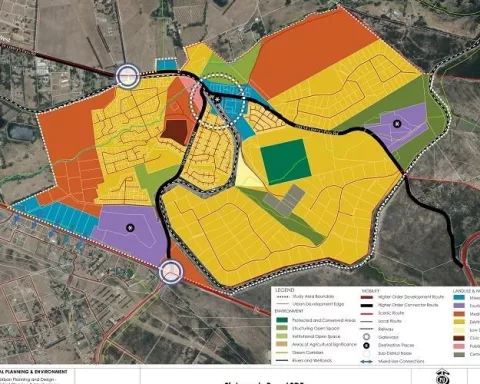

Beneath the relentless sun of Tafelsig, the [Swartklip Road Pump Station](https://capetown.today/cape-towns-weapon-against-power-cuts-the-steenbras-dam/) silently works at the edge of hope and hardship. This unassuming structure, with its constant thrum of machinery, stands as a vital artery in Cape Town’s complex network of water and sanitation. For the neighboring residents in Monwabisi Zone 4, the pump station’s presence symbolizes both progress and tension – a promise of steady services shadowed by persistent need.

The station’s location places it at a crossroad where urban ambition meets the lived realities of those often sidelined by formal systems. It offers the surrounding community reassurance that the basic needs of sanitation and hygiene can be met. Yet, its proximity also reveals a vulnerability: the pump house, designed to serve as a bulwark for public health, has become a magnet for those seeking access to another essential resource – electricity.

Within this charged landscape, everyday survival demands ingenuity. With formal electrical supply limited or unaffordable for many, the lure of Swartklip’s power grid becomes too strong to ignore. Residents, faced with little choice, have fashioned makeshift connections, threading a perilous network of cables through sand, grass, and fences. These acts of quiet defiance underscore the daily balancing act between necessity and risk for Cape Town’s marginalized.

Improvisation, Resistance, and the Risks of Informality

The story of illegal electricity connections at Swartklip Road echoes patterns of adaptation found in informal settlements worldwide. From the sprawling communities of Rio de Janeiro to the dense neighborhoods of Mumbai, ingenuity often thrives where formal infrastructure fails to reach. Makeshift wiring – what some call “clandestine connections” – offers an immediate solution in an environment where waiting for official intervention can mean years of deprivation.

This local improvisation, however, comes with steep consequences. Councillor Zahid Badroodien, the City of Cape Town’s mayoral committee member for water and sanitation, has repeatedly drawn attention to the persistence and dangers of these unauthorized links. When residents tap into the pump station’s electrical supply, they not only put themselves at risk of electrocution but also jeopardize the wider community. The added load can trigger malfunctions, leading to surges that stall the pump’s operation.

When the station falters, sewage can no longer move freely out of the settlement. The result is more than inconvenience – overflowing sewage seeps into public spaces, contaminates stormwater systems, and even infiltrates homes. The ripple effect turns a technical issue into a public health crisis, placing the most vulnerable at further risk. Photographs taken at the scene – showing city officials like Badroodien and Regional Pump Station Manager Lerato Mbuzwa inspecting tangled wires – bring this reality into sharp focus. Melted plastic, exposed copper, and the anxious faces of officials all convey the gravity of the situation.

Such scenarios reveal a hard truth: informal solutions, no matter how clever, seldom offer the stability or safety that lasting development demands. Yet, for many, these risks are preferable to going without electricity altogether.

Policy, Engagement, and the Limits of Enforcement

City officials have responded to the crisis with a blend of caution and resolve. In a move shaped by both regulation and empathy, municipal authorities convened meetings with local leaders and ward councillors, giving residents an opportunity to voluntarily remove their illegal connections. This approach reflects a delicate understanding – after decades marked by exclusion, South Africa’s cities now strive to balance enforcement with compassion.

By encouraging residents to take initiative, city leaders hope to foster a relationship of trust. But when voluntary compliance fails, the City acts to restore order. Disconnections proceed, restoring the pump station’s safety but sometimes deepening the sense of alienation and frustration in the community. As Councillor Badroodien explains to residents, these measures are not arbitrary; they are necessary to safeguard the entire sanitation system and preserve public health.

The process itself resembles a form of urban negotiation. Residents assemble at the perimeter, their emotions ranging from anger to resignation. City workers methodically dismantle the wire networks, while officials engage in frank dialogue. The outcome may restore the station’s function, but it also leaves lingering questions about the fundamental gaps in service delivery.

These events highlight a core insight from progressive urban theory: infrastructure is never just technical. Every physical system – whether it’s a pipeline, power cable, or pump – intersects with social forces. Swartklip’s predicament is a reminder that effective cities must recognize the interdependence of technical expertise and social understanding.

History, Hope, and the Ongoing Negotiation of Urban Life

Looking beyond the immediate crisis, deeper questions arise about the roots of informal practices and the gaps left by formal systems. Why do so many families feel compelled to risk hazardous connections? Why does reliable municipal service remain beyond reach for some, even decades after apartheid’s end? South Africa’s urban landscape still bears the imprint of spatial segregation and inequality; many communities were historically denied infrastructure and now play catch-up amidst rapid population growth.

A walk through Monwabisi reveals both hardship and resilience. Children dart between shacks, laughter mingling with conversations tinged with urgency about electricity, water, and opportunity. Older residents remember when every new line – whether officially sanctioned or home-rigged – marked a small victory. The term “izinyoka,” slang for those who make illegal connections, carries a tone not of scorn but reluctant acceptance. In the absence of the formal grid, creative survival becomes a way of life.

The City’s promise of ongoing engagement – through follow-up meetings with councillors and technical departments – signals an awareness that infrastructure cannot be separated from the communities it serves. The pump station represents not just a node of engineering but a crossroads of relationships: between citizens and officials, law and improvisation, risk and innovation. As architectural thinkers like Rem Koolhaas have observed, the most vital dimensions of urban infrastructure are often invisible until a crisis exposes their fragility.

Cape Town’s own history illustrates these lessons well. From the threats of drought during “Day Zero” to recurring sewer overflows in informal areas, the tension between formal and informal systems continues to drive both conflict and creativity. Each episode, including the Swartklip incident, reminds us that city-building is a perpetual process of negotiation – one shaped by both established designs and everyday improvisation.

In Tafelsig, the dance between enforcement and adaptation continues. The removal of illegal wires solves the immediate technical problem but does not erase underlying need. For every rule imposed, communities find ways to adapt; for every official initiative, there emerges a grassroots response. The city and its residents remain partners in an ongoing, if uneven, dialogue.

Ultimately, the story of Swartklip Road Pump Station transcends the drama of wires and pumps. It illuminates the ways cities are shaped not just by planners and politicians, but by the resilience and ingenuity of ordinary people. The pump house stands as both functional infrastructure and enduring symbol – a testament to the conflicts, compromises, and aspirations that animate the pulse of Cape Town’s urban life.

FAQ: Threading the Currents at Swartklip Road, Cape Town

1. Why do residents at Swartklip Road make illegal electricity connections?

Many residents at Swartklip Road resort to illegal electricity connections because formal power supply is either too expensive or unavailable. These makeshift connections provide immediate access to electricity, which is essential for daily living. However, they come with significant risks such as electrocution, damage to vital infrastructure like the pump station, and broader public health hazards like sewage overflow.

2. What risks do illegal electricity connections pose to the community?

Illegal connections often involve unsafe wiring that can cause electrocution and electrical fires. More critically, they overload the Swartklip Road Pump Station, a key part of Cape Town’s water and sanitation network. When the pump station fails due to electrical surges, sewage cannot be properly pumped out, leading to overflow that contaminates public spaces and homes, creating serious health risks for the entire community.

3. How is the City of Cape Town addressing illegal electricity connections at Swartklip Road?

The City adopts a balanced approach combining enforcement with community engagement. Officials hold meetings with residents and local leaders to encourage voluntary removal of illegal connections. When voluntary compliance is not achieved, the City proceeds with disconnections to protect the pump station and public health. This approach is part of a broader effort to build trust and foster dialogue, acknowledging residents’ struggles while enforcing necessary safety measures.

4. Why is formal electricity supply limited or unaffordable in areas like Swartklip Road?

Formal electricity supply in informal settlements like Swartklip Road is limited due to historical spatial inequality rooted in apartheid-era urban planning. Many such communities were denied access to reliable infrastructure and still face challenges related to poverty, rapid population growth, and service delivery backlogs. The cost of formal electrical connections and monthly fees can be prohibitive for low-income households, pushing residents toward informal alternatives.

5. What broader social and urban issues does the situation at Swartklip Road reveal?

The situation highlights the complex relationship between infrastructure, social inequality, and urban governance. It reveals how technical systems such as power and sanitation are deeply intertwined with historical exclusion, poverty, and the resilience of marginalized communities. The tension between enforcement and informal survival strategies underscores the need for urban policies that combine technical solutions with social understanding and inclusive development.

6. What steps can be taken to provide safer, more reliable electricity access for communities like Swartklip Road?

Long-term solutions include expanding affordable formal electricity infrastructure, improving urban planning to integrate informal settlements, and fostering community partnerships in service delivery. Investing in inclusive infrastructure development, social housing projects, and subsidized electricity programs can reduce the need for illegal connections. Additionally, continuous engagement between city officials and residents is essential to build trust and co-create sustainable urban services that meet everyone’s needs safely.

For more information about Cape Town’s infrastructure challenges and initiatives, you can visit the City of Cape Town’s official resources and local community forums.